SAN FRANCISCO — A 200-year-long drought 4,200 years ago may have killed off the ancient Sumerian language, one geologist says.

Because no written accounts explicitly mention drought as the reason for the Sumerian demise, the conclusions rely on indirect clues. But several pieces of archaeological and geological evidence tie the gradual decline of the Sumerian civilization to a drought.

The findings, which were presented Monday (Dec. 3) here at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union, show how vulnerable human society may be to climate change, including human-caused change.

"This was not a single summer or winter, this was 200 to 300 years of drought," said Matt Konfirst, a geologist at the Byrd Polar Research Center.

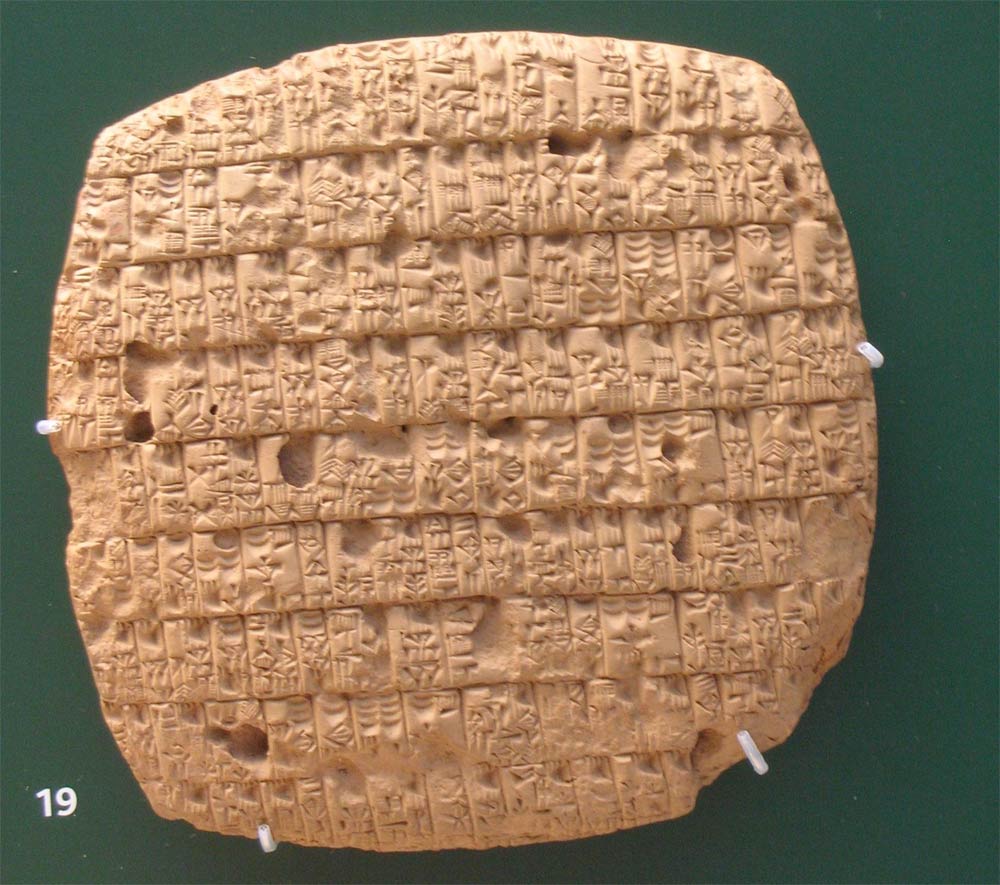

Beginning about 3500 B.C., the Sumerian culture flourished in ancient Mesopotamia, which was located in present-day Iraq. Ancient Sumerians invented cuneiform writing, built the world's first wheel and arch, and wrote the first epic poem, "Gilgamesh." [Image Gallery: Ancient Middle-Eastern Texts]

But after 200 to 300 years of upheaval, the Sumerian culture disappeared around 4,000 years ago, and the Sumerian language went extinct soon after that.

Konfirst wanted to see if a drought that spanned about 200 years may have caused the decline. Several geological records point to a long period of drier weather in the Middle East around 4,200 years ago, Konfirst said. The Red Sea and the Dead Sea had increased evaporation; water levels dropped at Lake Van in Turkey, and cores from marine sediments around that period indicate increased dust in the environment.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"As we go into the 4,200-year-ago climate anomaly, we actually see that estimated rainfall decreases substantially in this region and the number of sites that are populated at this time period reduce substantially," he said.

Around the same time, 74 percent of the ancient Mesopotamian settlements were abandoned, according to a 2006 study of an archaeological site called Tell Leilan in Syria. The populated area also shrank by 93 percent, he said.

"People still live in this region. It's not that the collapse of a civilization means that an area is completely abandoned," he said. "But that there's a sharp change in the population."

During the great drought, two waves of marauding nomads descended upon the region, sacking the capital city of Ur. After around 2000 B.C., ancient Sumerian gradually died off as a spoken language in the region. For the next 2,000 years, the tongue lingered on as a dead written language, similar to Latin in the Middle Ages, but has been completely extinct since then, Konfirst said.

The coincidence of the social upheaval, depopulation in the area and the geologic record of drought suggests climate change might have played a role in the loss of the Sumerian language, Konfirst said.

The findings also suggest that modern-day civilizations may be vulnerable to climate change, he said.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus