Image Gallery: 3-Year-Old Human Ancestor 'Selam' Revealed

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

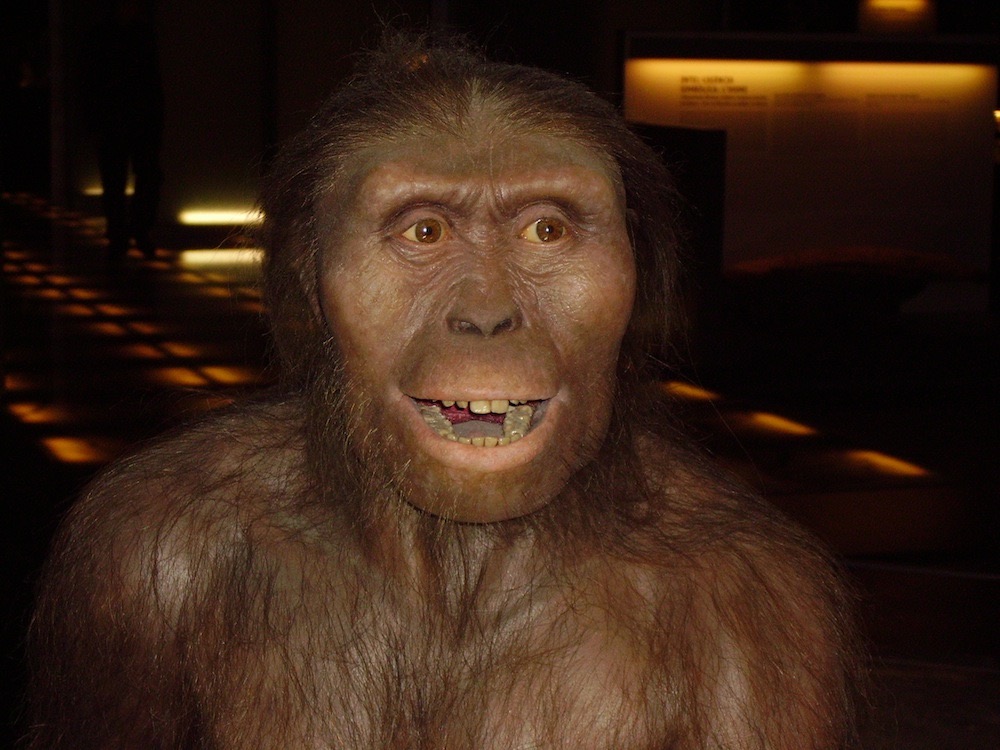

Upright Walkers?

Despite the ability to walk upright, early relatives of humanity represented by the famed "Lucy" fossil likely spent much of their time in trees, remaining very active climbers. Scientists know this not just from Lucy's skeleton, but also from the bones of a toddler Australopithecus afarensis, they reported in the Oct. 26, 2012, issue of the journal Science, and also in the May 22, 2017, issue of in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. In the more recent study, researchers have revealed the young girl's spine, now considered the oldest hominin spine known to date.

And Tree Climbers?

While scientists have known Lucy, an Australopithecus afarensis skeleton, and her kin were no knuckle-draggers, they have long debated how much time they spent in trees. The answer could reveal information about evolutionary forces that shaped the human lineage. (Shown here, a fragment of Lucy's lower arm bone.)

Selam Skeleton

To help resolve this controversy, scientists looked at two complete shoulder blades from the fossil "Selam," an exceptionally well-preserved skeleton of a 3-year-old A. afarensis girl dating back 3.3 million years from Dikika, Ethiopia. The arms and shoulders can yield insights on how well they performed at climbing. (Shown here, Selam's cranium, face and mandible.)

Fragile Shoulder Blades

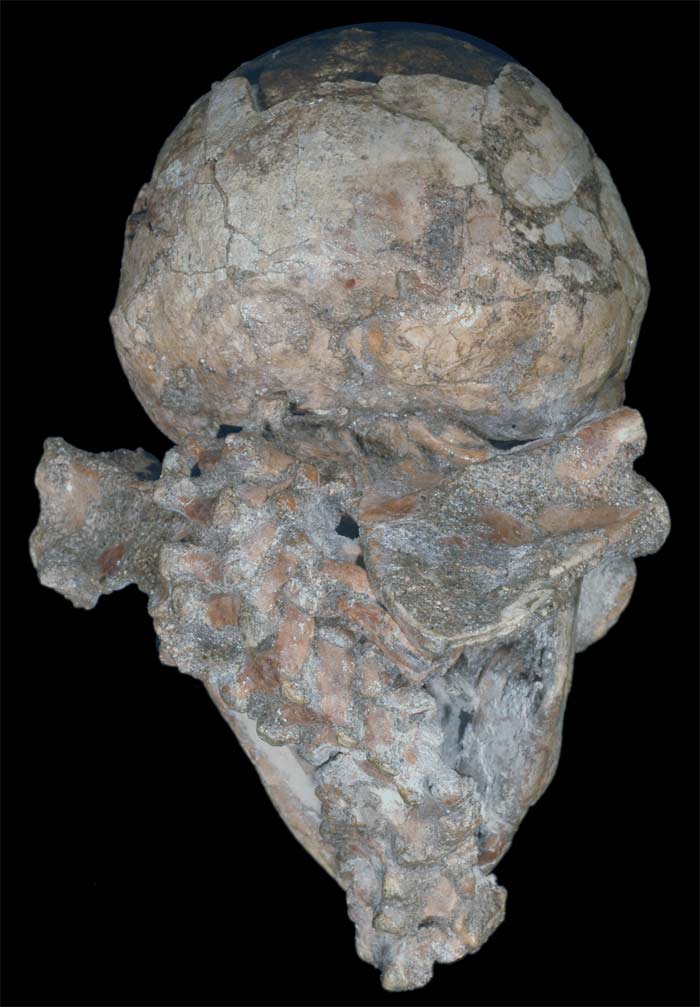

Researchers spent 11 years carefully extracting Selam's two shoulder blades from the rest of the skeleton, which was encased in a sandstone block. Here, a dorsal view of Selam's cranium, with the occipital bone and vertebral column visible. Dorsal views of both the complete right and the fragmentary left scapulae.

Finding Shoulder Bones

"Because shoulder blades are paper-thin, they rarely fossilize, and when they do, they are almost always fragmentary," Zeresenay Alemseged, a paleoanthropologist at the California Academy of Sciences. "So finding both shoulder blades completely intact and attached to a skeleton of a known and pivotal species was like hitting the jackpot." Here, another view of Selam's cranium and mandible, with the vertebrae and complete right scapula visible.

Socket Science

The researchers found these bones had several details in common with those of modern apes, suggesting they lived part of the time in trees. For instance, the socket for the shoulder joint was pointed upward in both Selam and today's apes, a sign of an active climber. In humans, these sockets face out to the sides. Shown here, Selam's cranium as well as the complete right scapula and the right ribs.

Like Modern Apes

The tiny right fossil shoulder blade of a 3-year-old Australopithecus afarensis female discovered in Dikika, Ethiopia who died 3.3 million years ago is held by lead author David J. Green of Midwestern University. The left blade (not pictured) is also preserved and both fossils display evidence that this early bipedal species maintained adaptations to climbing trees.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In Profile

Here, a right lateral view of Selam's cranium, face and mandible, with the upper and lower dentition visible.

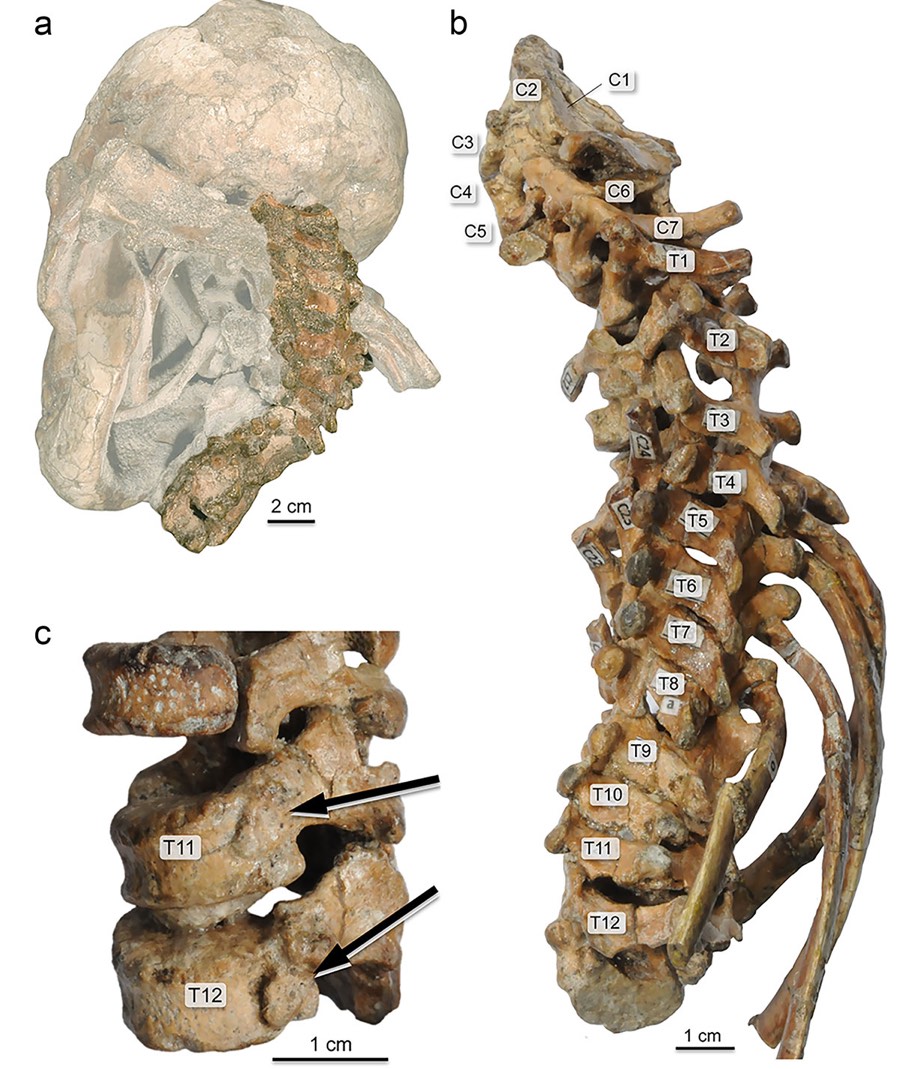

Selam's spine

The 3 million-year-old spine of Selam, an Australopithecus afarensis who died at the age of 2 or 3 in what is now Ethiopia. This is the oldest-complete cervical and thoracic spine from a human ancestor. The image in the upper left shows the spine as it was preserved in sandstone.

Oldest spine

The spine of the young Australopithecus afarensis Selam, a hominin who died some 3 million years ago.

Tiny bones

The delicate vertebrae of the A. aferensis Selam took years to painstakingly chip from the surrounding sandstone. The vertebral bodies are only about a half inch (1.2 centimeters) across.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus