Executions: 7 Gruesome Ways to Take a Life

A recent execution by lethal injection that went awry has renewed interest in the protection against "cruel and unusual punishment," as guaranteed in the U.S. Constitution.

On Tuesday (April 29), convicted murderer Clayton Lockett was executed by the state of Oklahoma, but not before he convulsed on the gurney, then raised his head and said, "Something's wrong." The execution was halted, but Lockett was later pronounced dead of a heart attack by prison officials.

Lockett's botched execution is shining a harsh light on capital punishment, which has a long and macabre history. Here are some such execution practices that were once common but later outlawed. [Mistaken Identity? 10 Contested Death Penalty Cases]

Hanging: The practice of tying a noose around a criminal's neck and suspending them until dead has been around since the medieval era. During that period, hangings became drunken public celebrations, with crowds of people gathering to drink, eat, fight, buy (or steal) souvenirs and otherwise whoop it up.

In 1833, Rhode Island banned public hangings, and hangings were conducted in private; other states soon followed. (Rhode Island was also the first U.S. state to outlaw all capital punishment, in 1852.) The last convict executed by hanging in the United States was Bill Bailey, hanged in Delaware in 1996. Though hanging is now banned by many countries, in others it remains the official method of killing convicts who are sentenced to death, and is still an option in New Hampshire and Washington.

Crucifixion: Since ancient times, tying or nailing a prisoner to a cross was an accepted means of implementing the death penalty. The practice was most famously used when Jesus was crucified by the Romans, who typically reserved the punishment for enemies of the state, slaves and thieves.

In A.D. 337, Emperor Constantine — the first Christian emperor of Rome — banned crucifixion for all crimes. It was also practiced in Japan during World War II; sporadic reports indicate crucifixion has been used as recently as 2002 in the handful of countries where it is still permitted.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

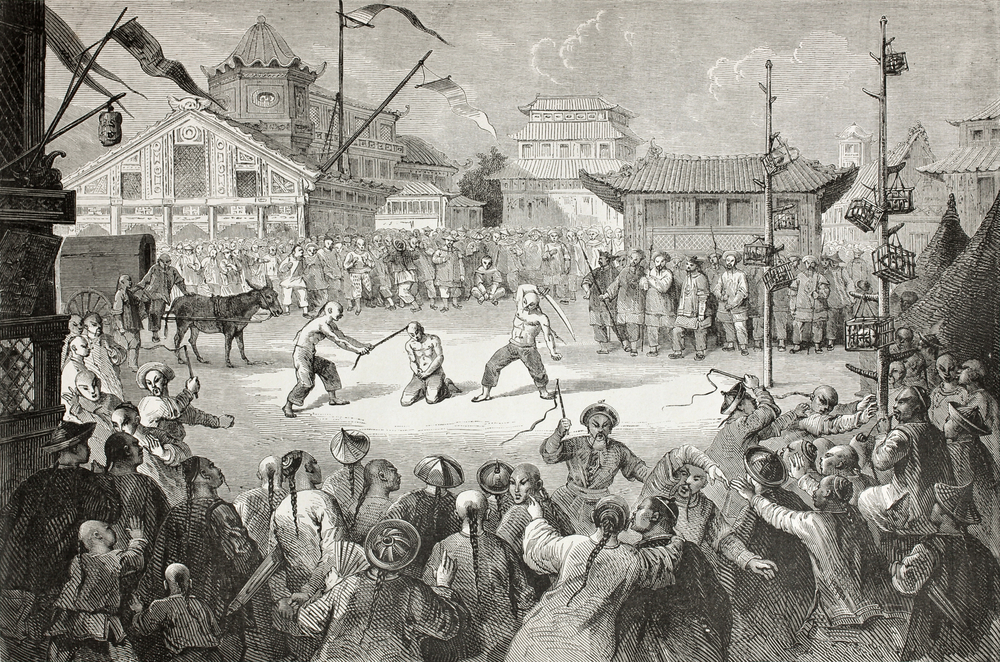

Ling Chi: People often use the term "death of a thousand cuts" to describe a slow decline caused by many small wounds. In China, cutting into a person's flesh and then gradually slicing off fingers, ears and other body parts until they lost consciousness and bled to death was known as "ling chi."

Though a handful of 19th-century accounts by Westerners who claim to have witnessed the practice exist, some of these accounts are considered exaggerations. Death by ling chi was finally outlawed in China in 1905.

Electrocution: In 1903, Thomas Edison demonstrated the power of electricity by attaching wires to Topsy the Elephant, then throwing the switch and electrocuting the unfortunate animal. Edison had previously electrocuted numerous cats and dogs at his laboratories.

The practice of electrocuting prisoners soon caught on — it was seen as a more humane way of dispensing with criminals. But because of frequent mishaps and botched electrocutions, the practice soon fell out of favor as lethal injections became more common. There are only six places in the world that now allow death by electrocution: Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, South Carolina, Tennessee and Virginia.

Drawing and Quartering: In a method of execution peculiar to England, prisoners were hanged, then disemboweled and chopped into four pieces. In a particularly sinister twist, some prisoners had each wrist and ankle tied to a rope that was then attached to a horse or ox—as the animals were driven away, the victim's body was slowly ripped into four quarters.

The punishment was reserved for men (out of a misguided sense of public decency), and the last man drawn and quartered was in 1839. After government leaders concluded that drawing, quartering and other gruesome forms of capital punishment caused more harm than good in the public's mind, the practice was abolished in 1870.

Brazen Bull: For sheer inventiveness, the brazen bull (sometimes referred to as the bronze bull) stands apart: A large bull was cast from bronze with a hollow interior and a door in its side was placed in a public square. The unlucky criminal was forced inside the bull, and with the door locked, a fire was lit beneath the bronze bull.

Pipes inside the bull's neck and head converted the criminal's screams into sounds like the bellowing of a bull. Eventually, of course, the prisoner burned to death. The infamous device was apparently used by Phalaris, ruler of Sicily, with abandon during his reign (c. 570 to 554 B.C.). When Phalaris was overthrown, he met his end inside the same brazen bull that came to symbolize his tyranny. [Dictator Deaths: How 13 Notorious Leaders Died]

Breaking Wheel: Also known as the Catherine Wheel (after St. Catherine of Alexandria, who reportedly met her end on the device), the breaking wheel was a large wooden wheel with several spokes. Lashed to the wheel, criminals were then whipped, bludgeoned, hammered or otherwise beaten, resulting in broken bones, shock, blood loss and eventual death.

Like many public executions, the breaking wheel was employed as a deterrent to onlookers who may have had criminal intent, and was used in colonial America to punish slaves convicted of revolt. The last known use of the breaking wheel occurred in Prussia in 1841.

Follow Marc Lallanilla on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.