Like memory, human intelligence is probably not confined to a single area in the brain, but is instead the result of multiple brain areas working in concert, a new review of research suggests.

The review by Richard Haier of the University of California , Irvine , and Rex Jung of the University of New Mexico proposes a new theory that identifies areas in the brain that work together to determine a person's intelligence.

"Genetic research has demonstrated that intelligence levels can be inherited, and since genes work through biology, there must be a biological basis for intelligence," Haier said.

The review of 37 imaging studies, detailed online in the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences, suggests that intelligence is related not so much to brain size or a particular brain structure, but to how efficiently information travels through the brain.

"Our review of imaging studies identifies the stations along the routes intelligence information processing takes," Haier said. "Once we know where the stations are, we can study how they relate to intelligence."

The new theory might eventually lead to treatments for low IQ, the researchers say, or to ways of boosting the IQ of people with normal intelligence.

P-FIT

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

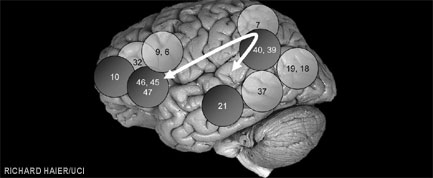

In their review, Haier and Jung compiled a list of all the brain areas previous neuroimaging studies had found to be related to intelligence, placing greater emphasis on those areas that appeared multiple times. The list they came up with suggests that most of the brain areas thought to play a role in intelligence are clustered in the frontal and parietal lobes. Furthermore, some of these areas area also related to attention and memory and to more complex functions such as language. The pair does not think this is a coincidence. In their Parieto-Frontal Integration Theory (P-FIT), they suggest that intelligence levels are based on how efficiently these brain areas communicate with one another.

Haier says the new theory sidesteps the sticky question of what intelligence is, something that scientists have yet to agree on. "In every single study that we reviewed, there was a different measure of intelligence," Haier said. "There's controversy about what is the best measure of intelligence. There's controversy over how broad or narrow the definition of intelligence should be. Our work really goes beyond those questions and basically says that irrespective of the definition of intelligence you use in neuroimaging studies, you find a similar result."

Earl Hunt, a neuroscientist at the University of Washington , who was not involved in the research, said the P-FIT model highlights the progress scientists have made in recent years toward understanding the biological basis of intelligence. "Twenty-five years ago researchers in the field were engaged in an unedifying discussion of the relation between skull sizes and intelligence test scores," Hunt said.

Building upon previous work

Haier and Jung were also behind other important intelligence-related studies. In 2004, they found that regions related to general intelligence are scattered throughout the brain and that the existence of a single "intelligence center" was unlikely.

And in a 2005 study, they found that while there is essentially no difference in general intelligence between the sexes, women have more white matter and men more gray matter. Gray matter represents information processing centers in the brain, and white matter links the centers together. The finding suggested that no single structure in the brain determines general intelligence and that different types of brain designs can produce equivalent intellectual performance.

Knowing what determines intelligence might lead to treatments for diseases of intelligence like mental retardation, Haier said.

"It would be important to now how intelligence works to determine if there's any way to treat low IQ," Haier told LiveScience. "If you can treat low IQ in mental retardation because you identify something wrong in the brain that's affecting intelligence, then that raises the question of whether you can raise IQ in people that don't necessarily have the brain injuries."