The Culture of Blasphemy Among Nonbelievers

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The international news media has recently focused on Terry Jones, the leader of a small church in Gainesville, Fla., who has threatened to burn copies of Islam's holiest book, the Koran, on Sept. 11. This has, of course, garnered plenty of controversy and howls of protest from Muslims over Jones' blasphemous actions.

In his book "Blasphemy" (Knopf, 1993), Leonard Levy notes that what a group of people considers blasphemous "is a litmus test of the standards a society believes it must enforce to preserve its unity, its peace, its morality, and feelings, and the road to salvation."

In the Muslim world, blasphemy is considered a grave offense, punishable by death. Islam, however, is hardly unique in that regard. Early Christians were intolerant of blasphemy, and in fact Leviticus 24:16 specifically calls for blasphemers to be killed ("He that blasphemeth the name of the Lord shall surely be put to death, [and] all the congregation shall certainly stone him" KJV). The Hebrew Bible goes even further, specifying that those who offend God should be butchered alive and their homes destroyed: "Every people, nation, and language, which speak any thing amiss against God shall be cut in pieces, and their houses shall be made a dunghill" (Daniel 3:29).

So, in all religions — in theory anyway — this insulting God stuff is serious business.

Prof. Reinhold Aman, editor of the scholarly "Maledicta: The International Journal of Verbal Aggression," told LiveScience, "In puritanical America, before the sex-and-excrement curses took over around the mid-1990s, blasphemy was taken very seriously. Even such now-mild blasphemies as 'hell,' 'Jesus,' and 'goddamn' were grave offenses. Thus many euphemisms were created to blaspheme without actually blaspheming, such as 'heck,' 'jeez!', 'cheese and crackers!', 'cripes!', 'gosh!', 'golldarn!' and the like."

"In Catholic regions, the most taboo and sacred subject is religion," Aman said. "Therefore, Catholics blaspheme using the name of God, Holy Mary, saints, and church implements. Some of the most common blasphemies are 'Sacrament!', 'Crucifix!' and 'Cross!'; 'Mary, you whore!' and 'God, you pig!'; and 'By the 24 balls of the 12 apostles of Christ!'"

Why are Muslims so upset? Jews don't get upset when Gentiles eat pork. Though burning a Torah or a Bible would be considered in poor taste and disrespectful, neither Jews nor Christians would threaten death to anyone who dared to do such a thing. So why would Muslims care what non-Muslims do with their personal property (if that property happens to be a Koran)?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

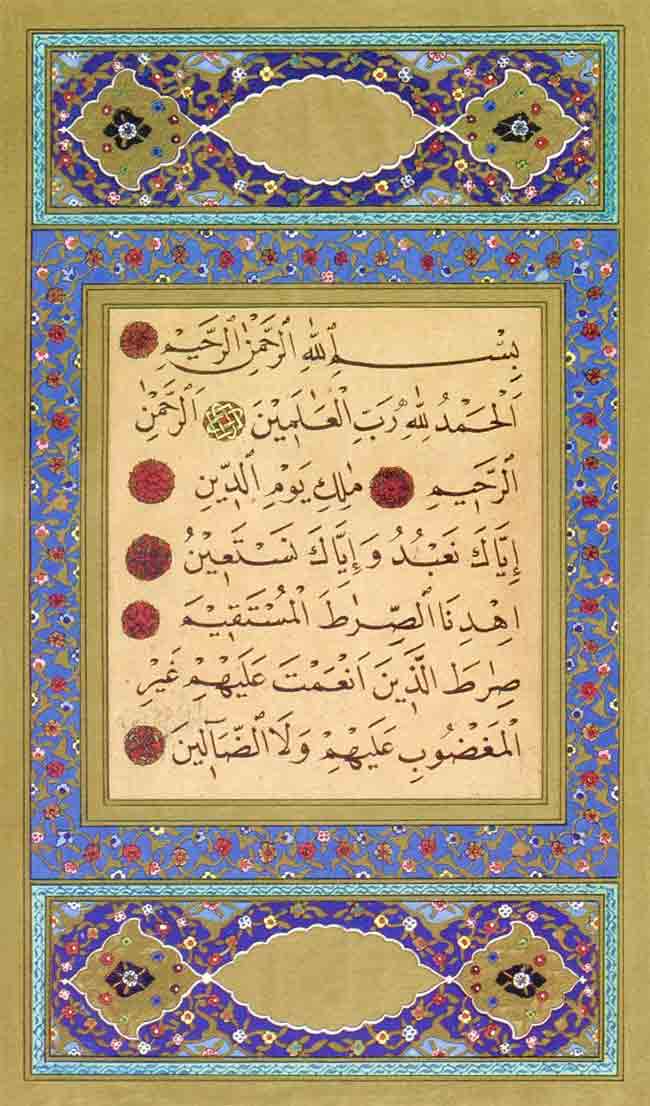

Among the world's major religions Muslims are unusually sensitive to blasphemy when it comes to their prophet, their god, and their holy book. The Koran is considered by Muslims to be the final, complete and inerrant word of Allah as revealed to the prophet Mohammed. It is, therefore, far more than a collection of writings, and the physical book itself is revered. According to Stanford University's Islamic scholar Azim Nanji, "A copy of the Koran is given an honored place in the house, where it is generally placed at a higher level than other belongings and furnishings. Muslims often carry a text from the Koran on their persons in a small ornamental amulet."

Fundamentalist Christians have also denounced blasphemy in recent years, often concerned with how Jesus is portrayed (for example in films such as Martin Scorsese's "The Last Temptation of Christ" and Ron Howard's "The Da Vinci Code"). Some Christians have also protested art exhibits such as those featuring a photograph by artist Andres Serrano of a small plastic crucifix submerged in urine, titled "Piss Christ."

Yet Muslim protests against blasphemy are by far the best-known and most volatile. British author Salman Rushdie's 1988 book "The Satanic Verses" (Picador) was called blasphemous by many Muslim leaders for an irreverent depiction of Mohammed. The following year a fatwa (death sentence) was issued by Iran's Ayatollah Khomeni, who called for devout Muslims to kill Rushdie. Several attempts were made on his life, and Rushdie went into hiding for years. In 2005, cartoons of Mohammed were printed in a Danish newspaper, triggering protests, fire bombings, and riots, which resulted in the deaths of about 100 people.

While some blasphemy protests have turned violent, other recent Western depictions of Mohammed have received little criticism, such as a 2008 satirical board game called "Playing Gods" (which included a Muslim figure as a playing piece), and a 2009 online video game called "Faith Fighter."

Atheists and humanists consider blasphemy to be a victimless crime, though as Levy notes the idea of nonbelievers being blasphemous is a relatively recent development. Those accused of (and executed for) blasphemy have usually been religious people; indeed, "For most of history, blasphemers have been devout Christians."

Benjamin Radford is managing editor of the Skeptical Inquirer science magazine. His new book is Scientific Paranormal Investigation; this and his other books and projects can be found on his website. His Bad Science column appears regularly on LiveScience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus