Researchers capture elusive particle trios at room temperature

It's a boon for quantum computing.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Researchers have found a way to trap and study elusive particle trios called trions at room temperature.

Previously, trions could be studied only in super-cooled conditions. These trios consist of either two electrons and an electron hole (a space in the electronic structure that an electron could fill, but where there is no electron), or two holes and one electron. They're bound together only weakly, meaning they fall apart quickly —— not a boon for researchers trying to study them for applications in quantum computing and electronics.

Now, scientists led by YuHuang Wang, a chemist at the University of Maryland, have found a way to stabilize trions at room temperature.

"This work makes synthesizing trions very efficient and provides a method for manipulating them in ways we haven't been able to before," Wang said in a statement. "With the ability to stabilize and trap trions, we have the potential to build a very clean system for studying the processes governing light-emitting diodes and photovoltaics and for developing quantum information technologies."

Related: The 18 biggest unsolved mysteries in physics

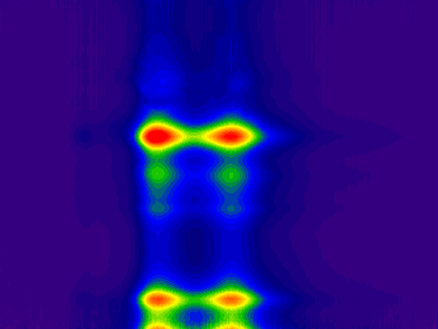

To trap the trions, the researchers started with single-walled carbon nanotubes, then used a chemical reaction to create tiny defects in the tube walls. These defects trap charged particles. To create those charged particles, the researchers directed photons, or light particles, at the nanotubes. These photons excited electrons in the nanotubes out of their lowest energy state, known as the ground state, leaving an electron hole behind. The combination of the electron and the hole is called an exciton. The excitons then became trapped — alongside free electrons (the ones that had popped out of their ground states) — in the defects on the tube walls, binding together into trions of two electrons and one hole.

The photons also allowed the researchers to observe these trapped trions. When the trapped trions decay, or fall apart, they release a photon, creating a flash of luminescence at a tell-tale wavelength that researchers could detect and identify. The experiment resulted in trions seven times brighter and 100 times longer-lived than trions observed in super-cooled experiments.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The energy level of the trion is controlled by the well in the nanotube wall, and the researchers can manipulate the characteristics of the well, Wang said. That means they can also control the energy and stability of the trions, altering atomic properties like charge and electron spin. This, in turn, could be used in applications such as photovoltaics, or the conversion of light into energy.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus