Astronomers spot violent afterglow of 2 massive planets that collided in a distant star system

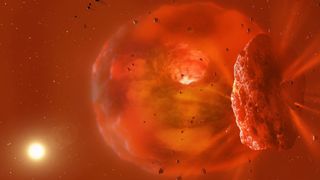

Astronomers detected the dusty afterglow of a massive planetary collision in a star system 3,600 light-years away, where two giant icy worlds met their end.

Astronomers have spotted the wreckage left by a massive collision between two huge icy planets around a distant, sunlike star.

Using a NASA spacecraft that monitors the sky for asteroids, the scientists also detected the bright afterglow generated by the planetary smash-up and the resulting dust cloud that crossed the face of the system's parent star, dimming it significantly.

A curious astronomer tipped the team off about the collision after spotting that the star — designated ASASSN-21qj and located around 3,600 light-years from Earth — had a strange light output that doubled in intensity in infrared light before fading in visible light three years later.

"An astronomer on social media pointed out that the star brightened up in the infrared over a thousand days before the optical fading. I knew then this was an unusual event," Matthew Kenworthy, study co-lead and a researcher at Leiden University, said in a statement. "To be honest, this observation was a complete surprise to me."

Related: 'Impossible' new ring system discovered at the edge of the solar system, and scientists are baffled

The researchers continued to study ASASSN-21qj for two years, watching how its brightness changed over time. They published their findings on Oct. 11 in the journal Nature.

The team found that the collision of two ice giants likely caused the system to double in brightness at infrared wavelengths three years before ASASSN-21qj started to fade in visible light.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Simulating a cool collision

The researchers conducted a simulation of how such a collision would proceed, modeling the initial impact and then the dispersal of particles flung out by the clash. This revealed that the ASASSN-21qj planets likely collated into a single body after the collision.

The simulation enabled the team to determine how the debris cloud would have expanded outwards from the collision site, taking three years to travel far enough to cover ASASSN-21qj as seen from Earth, causing it to dim in visible light.

"Our calculations and computer models indicate the temperature and size of the glowing material, as well as the amount of time the glow has lasted, is consistent with the collision of two ice giant exoplanets," co-lead author Simon Lock, a researcher at the University of Bristol, explained.

Determining the temperature of this planetary wreckage also helped the team to deduce what the infrared glow created by this violent event would look like. An emission matching this profile had been detected by NASA's Near-Earth Object Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (NEOWISE) spacecraft, which hunts for asteroids and comets within our solar system.

The scientists aren't finished observing ASASSN-21qj and its planetary wreckage just yet. They will watch the system over the coming years, and they expect that the debris cloud will spread out along the orbit of the destroyed planets. The researchers may attempt to catch light scattering off this dust cloud using ground-based observatories and space-based telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope.

"It will be fascinating to observe further developments. Ultimately, the mass of material around the remnants may condense to form a retinue of moons that will orbit around this new planet," study co-author Zoë Leinhardt, an associate professor of Astrophysics at the University of Bristol, said.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. who specializes in science, space, physics, astronomy, astrophysics, cosmology, quantum mechanics and technology. Rob's articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University

Most Popular