How many stars in the Milky Way die each year?

Stars die at different rates depending on how they kick the bucket.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When you gaze up at the stars, you see the same constellations that the ancient Greeks, and even the early hunter-gatherers, did. But it's also a changing tapestry, as new stars are constantly being born, and others are dying. In fact, that will be the fate of our own sun in roughly 5 billion years.

But how quickly does the night sky change, and in our galaxy, the Milky Way, how many stars die each year?

According to James De Buizer, a research scientist at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute, it's complicated.

First, it helps to clarify what it means for a star to die. Stars are enormous balls of hot gas sustained by nuclear fusion that converts hydrogen to helium inside the core. Stars die when nuclear fusion stops. There are two main ways this can happen, and the way a star dies depends on its mass.

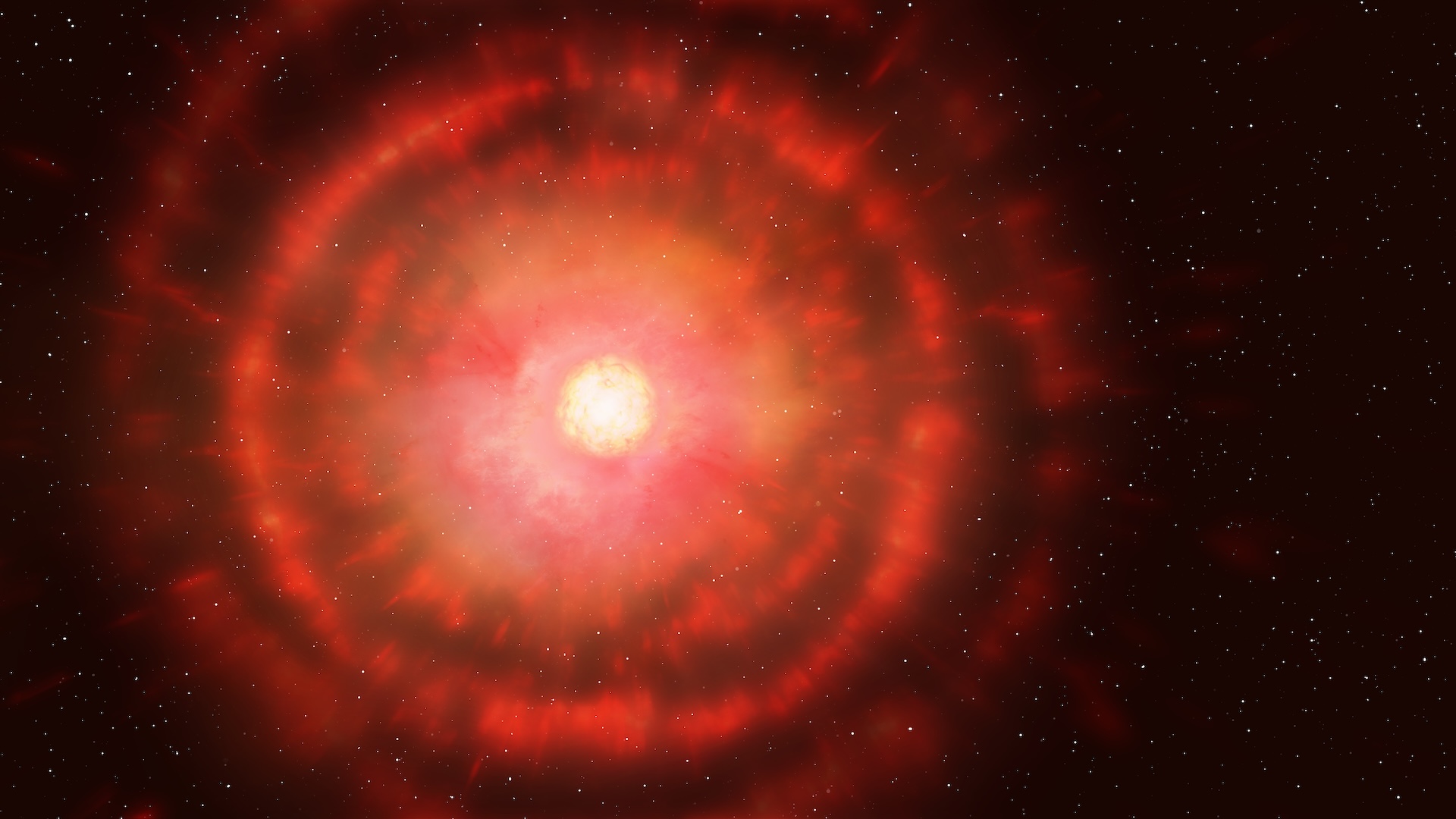

For low-mass stars, nuclear fusion ends when all the hydrogen in the star's core is converted to helium. Without the heat and subsequent outward pressure of fusion, the star collapses onto itself. During this collapse, the pressure on the core becomes so intense that the remaining helium starts to fuse into carbon and release energy, NASA explains. The star's outer atmosphere puffs out and turns reddish to create what's known as a red giant.

Related: Could a star ever become a planet?

Eventually, the star sheds this puffy atmosphere, leaving behind a dense object known as a white dwarf. About 97% of the stars in the Milky Way, including the sun, are destined to become white dwarfs, De Buizer said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Astronomers can see white dwarfs because they emit a unique light signature. They use this information, plus the rate of star formation and the total number of stars, to figure out how many stars die each year. It's estimated that one white dwarf forms every two years, De Buizer said.

For stars that are eight or more times the mass of the sun, there's a different death process. These massive stars make up only about 3% of the Milky Way's stars, but their impacts are impressive.

"These are the really violent, energetic events that I think some people might characterize as death," said Eric Borowski, an astrophysics graduate student at Louisiana State University.

This kind of star fuses heavier and heavier elements in its core, eventually becoming so massive that it cannot hold itself up against gravity, Borowski said. The result is a huge explosion called a supernova. The star's core lives on as either a neutron star or a black hole, according to NASA.

The last recorded observation of a supernova in the Milky Way was in 1604, yet astronomers estimate that a supernova happens once or twice a century in the galaxy.

So why has it been more than 400 years since one has been detected in our galaxy? Astronomers' best estimates are complicated by the Milky Way's shape and the dense clouds of gas and dust.

"There could be supernovae going off on the other side of the galactic center … but there's so much stuff between us … we're not going to see them," De Buizer said.

In total, with a white dwarf forming every two years or so, plus a couple of supernovas happening every 100 years, that's a grand total of nearly 53 stars dying each century in the Milky Way, or about one star every 1.9 years.

Understanding the stages of star death is how astronomers piece together star life cycles, De Buizer said.

Editor's note: This article was updated at 9:55 a.m. EDT on June 3 to clarify that about one star dies every 1.9 years.

Hannah Loss is a science journalist based in Boston. She covers the environment and has written for Scientific American, Sierra and Inside Climate News. Hannah graduated from Tufts University with a B.A. in English and environmental studies. She received a Master's degree in journalism from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus