Mysterious Indus Valley People Gave Rise to Modern-Day South Asians

Who were the ancient people from the mysterious Harappan Civilization?

Ancient DNA evidence reveals that the people of the mysterious and complex Indus Valley Civilization are genetically linked to modern South Asians today.

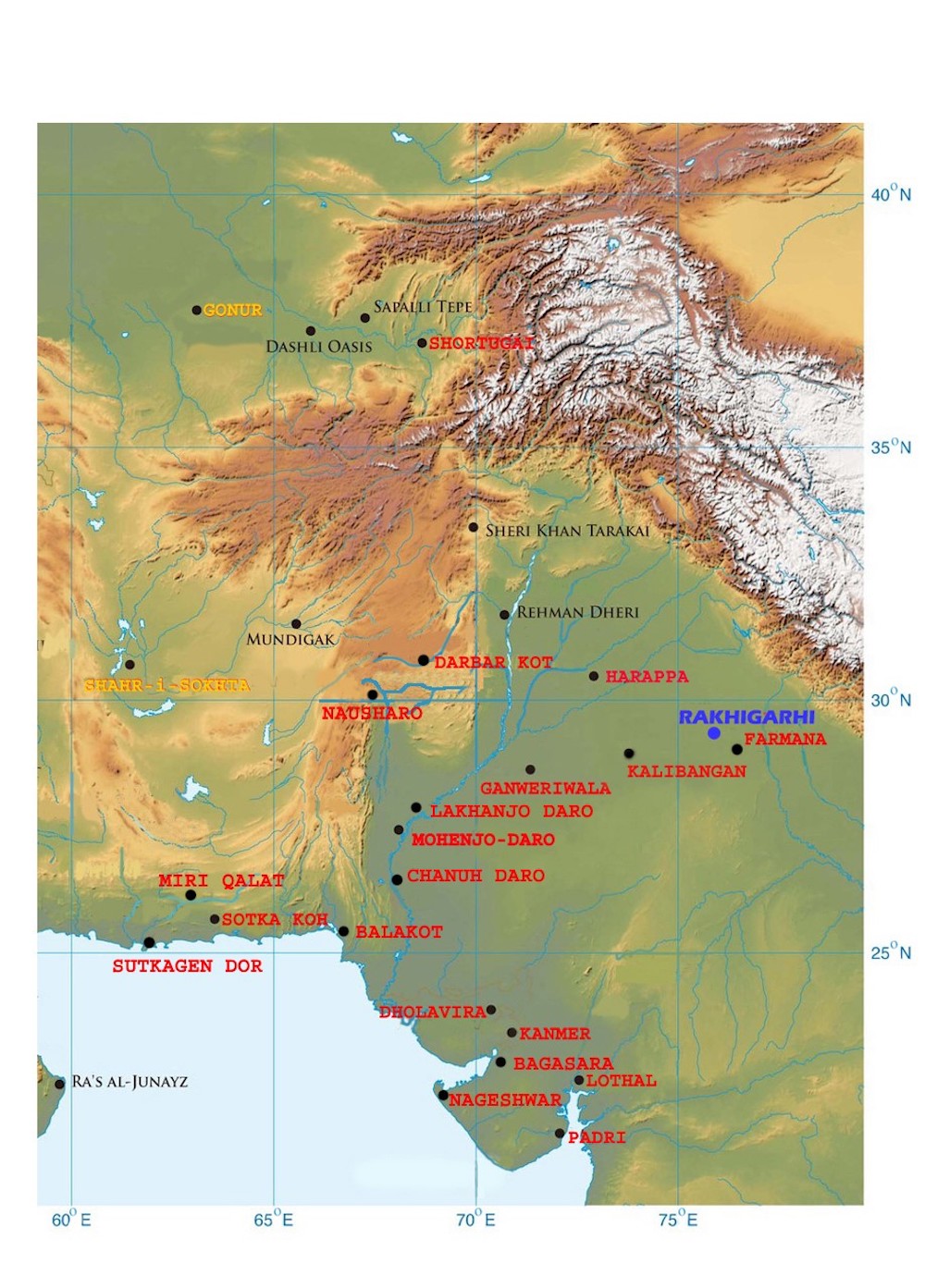

The same gene sequences, drawn from a single individual who died nearly 5,000 years ago and was buried in a cemetery near Rakhigarhi, India, also suggest that the Indus Valley developed farming independently, without major migrations from neighboring farming regions. It's the first time an individual from the ancient Indus Valley Civilization has yielded any DNA information whatsoever, enabling researchers to link this civilization both to its neighbors and to modern humans.

The Indus Valley, or Harappan, Civilization flourished between about 3300 B.C. and 1300 B.C. in the region that is now covered by parts of Afghanistan, Pakistan and northwestern India, contemporaneous with ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. The people of the Indus Valley forged an impressively advanced civilization, with large urban centers, standardized systems of weights and measurements and even drainage and irrigation systems. Yet despite that sophistication, archaeologists know far less about the civilization than that of ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia, in part because the Indus Valley writing system hasn't yet been deciphered.

Cracking Codes: 5 Ancient Languages Yet to Be Deciphered

Elusive DNA

Gathering ancient DNA from the Indus Valley is an enormous challenge, Vagheesh Narasimhan, one of the leading authors of the new research and a postdoctoral fellow in genetics at Harvard Medical School, Live Science, because the hot, humid climate tends to degrade DNA rapidly. Narasimhan and his colleagues attempted to extract DNA from 61 individuals from the Rakhigarhi cemetery and were successful with only one, skeleton likely belonging to a female which was found nestled in a grave amid round pots, her head to the north and feet to the south.

The first revelation from the ancient gene sequences was that some of the inhabitants of the Indus Valley are connected by a genetic thread to modern-day South Asians. "About two-thirds to three-fourths of the ancestry of all modern South Asians comes from a population group related to that of this Indus Valley individual," Narasimhan said.

Where the Indus Valley individual came from is a more difficult question, he said. But the genes do suggest that the highly agricultural Indus people were not closely related to their farming neighbors in the western part of what is now Iran.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We were able to examine different associations between the advent of farming in that part of the world with the movement of people in that part of the world," said Narasimhan.

Farming, Narasimhan said, first began in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East around 10,000 years ago. No one knows precisely how it spread from there. Did agriculture pop up independently in areas around the globe, perhaps observed by travelers who brought the idea to plant and cultivate seeds back home? Or did farmers move, bringing their new agricultural lifestyle with them?

In Europe, the genetic evidence suggests that the latter is true: Stone Age farmers introduced Southern Europe to agriculture, then moved north, spreading the practice as they went. But the new Indus Valley genetic evidence hints at a different story in South Asia. The Indus Valley individual's genes diverged from those of other farming cultures in Iran and the Fertile Crescent before 8000 B.C., the researchers found.

"It diverges at a time prior to the advent of farming almost anywhere in the world," Narasimhan said. In other words, the Indus Valley individual wasn't the descendent of wandering Fertile Crescent farmers. She came from a civilization that either developed farming on its own, or simply imported the idea from neighbors — without importing the actual neighbors.

Both immigration and ideas are plausible ways to spread farming, Narasimhan said, and the new research suggests that both happened: immigration in Europe, ideas in South Asia. The results appear today (Sept. 5) in the journal Cell.

Complex populations

The researchers also attempted to link the Indus Valley individual to his or her contemporaries. In a companion paper published today in the journal Science, the researchers reported on ancient and modern DNA data from 523 individuals who lived in South and Central Asia over the last 8,000 years. Intriguingly, 11 of these people — all from outside the Indus Valley — had genetic data that closely matched the Indus Valley Individual. These 11 people also had unusual burials for their locations, Narasimhan said. Together, the genetic and archaeological data hint that those 11 people were migrants from the Indus Valley Civilization to other places, he said.

However, these conclusions should be viewed as tentative, warned Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, an archaeologist and expert on the Indus Valley Civilization at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who was not involved in the new research. Archaeological evidence suggests that Indus Valley cities were cosmopolitan places populated by people from many different regions, so one person's genetic makeup might not match the rest of the population. Furthermore, Kenoyer said, burial was a less common way of dealing with the dead than cremation.

"So whatever we do have from cemeteries is not representative of the ancient populations of the Indus cities, but only of one part of one community living in these cities," Kenoyer said.

And though the Indus individual and the 11 potential migrants found in other areas might have been related, more ancient DNA samples will be needed to show which way people, and their genes, were moving, he said.

Narasimhan echoed this need for more data, comparing the cities of the Indus Valley to modern-day Tokyo or New York City, where people gather from around the world. Ancient DNA is a tool for understanding these complex societies, he said.

"Population mixture and movement at very large scales is just a fundamental fact of human history," he said. "Being able to document this with ancient DNA, I think, is very powerful."

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

- Album: The Seven Ancient Wonders of the World

- Top 10 Mysteries of the First Humans

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.