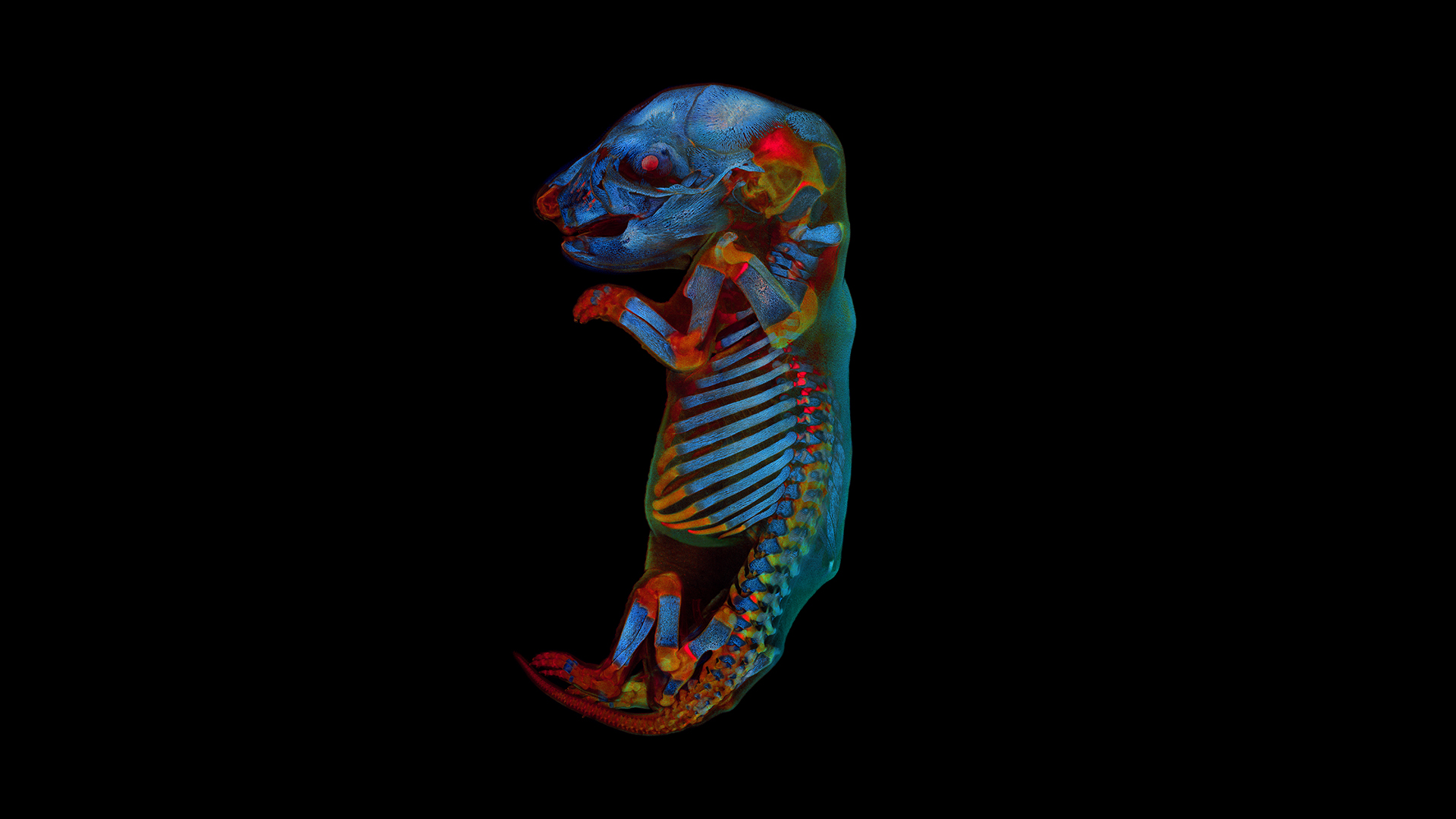

Glowing, red-eyed rat fetus is global photo contest's gorgeously creepy winner

Butterfly wing scales, neurons and dividing cells showcased the beauty of microscopy.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A luminous image of a rat fetus with radiant crimson eyes recently captivated the judges of an international photo competition run by Olympus, nabbing the photographer the title of Global Winner for 2020.

Werner Zuschratter, a researcher in the Special Lab for Electron and Laserscanning Microscopy at the Leibniz Institute of Neurobiology in Magdeburg, Germany, photographed the fetus using confocal microscopy, an optical imaging technique that photographs tiny objects through a pinhole in order to increase contrast and clarity in images, according to a description of the photo on the website for the contest: the Olympus Global Image of the Year Award.

The fetus was in its 21st day of development and measured just 1.2 inches (3 centimeters) long, Zuschratter told Live Science in an email. It had previously been chemically treated to render its skin and muscles translucent; in the image, fluorescent dyes and natural fluorescence in body tissues lit up the fetal skeleton and other internal structures with an eerie glow.

Related: Magnificent microphotography: 50 tiny wonders

Olympus' annual competition, now in its second year, celebrates extraordinary microscopy of living organisms. A team of experts evaluates images for their scientific impact and artistic presentation, as well as for the demonstrated proficiency of the photographer using a microscope, contest organizers wrote in a statement.

By laser-scanning the fetus multiple times and then combining stacks of images in different spectral ranges, Zuschratter revealed its bones and tissues in exceptional detail. Scanning the tiny rat took nearly 25 hours, and one of the trickiest parts was keeping the preserved fetus perfectly immobile during the motorized image capture process, Zuschratter told Live Science.

Post production was also a challenge, with Zuschratter using software to digitally stitch together individual image "tiles" to make the prizewinning photo. Another research team had originally prepared the specimen more than 25 years ago "to explore the effects of pharmaceuticals on embryonic development," Zuschratter said. For those experiments, the scientists rendered the fetus transparent and stained the skeleton red.

"All other soft tissue remained unstained and was almost transparent," Zuschratter explained. He removed the sample from storage to test newer techniques for clearing preserved tissue in preparation for microscopy, and to examine the appearance of different body tissues' natural fluorescence across the spectrum and over time.

Another standout image, a mesmerizing wheel of vibrant color, earned photographer XinPei Zhang the contest's Asia-Pacific Regional Award. Zhang created the vivid collage from images of wing scales that represent more than 40 species of butterflies, photographing the scales one at a time and then assembling them into a colorful circle.

For this year's competition, photographers from 61 countries submitted more than 700 microscope images. Entries that earned honorable mentions featured myriad tiny wonders, such as amino acid crystals illuminated by polarized light; delicate pollen-producing structures in flowers; threadlike collagen fibers in snakeskin; and the muscles of a sea urchin, to name just a few. These winners and more are available to view on the contest website.

Creating these beautiful images means striking a delicate balance between satisfying aesthetic criteria and representing an object accurately, Zuschratter said. But highlighting the beauty of nature, as the contest photos do, is also important — particularly when it reveals the often-unseen beauty of things too small to glimpse with the naked eye.

"Art is always a source of inspiration for science," he said in the email. "Moreover, with nice images you may get the public excited about complex topics."

Originally published on Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus