Physicists make record-breaking 'quantum vortex' to study the mysteries of black holes

Physicists created a 'quantum vortex,' which flows with 500 times less viscosity than water and could be used to study the space-time warping caused by black holes.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have created a giant quantum tornado inside a helium superfluid, and they want to use it to probe the enigmatic nature of black holes.

The whirlpool — made from liquid helium cooled to near absolute zero — moves without friction, making it mimic the way rotating black holes warp the space-time that surrounds them.

By studying the vortex, physicists could glean important insight into the behavior of the cosmic monsters. The researchers published their findings March 20 in the journal Nature.

"Using superfluid helium has allowed us to study tiny surface waves in greater detail and accuracy than with our previous experiments in water," lead author Patrik Svancara, a physicist at the University of Nottingham in the U.K., said in a statement. "As the viscosity of superfluid helium is extremely small, we were able to meticulously investigate their interaction with the superfluid tornado and compare the findings with our own theoretical projections."

The workings of black holes remain a persistent mystery for physicists. The known laws of physics break in the presence of these extreme objects' infinite gravitational pulls. For those looking to combine Einstein's theory of general relativity with quantum mechanics, this means black holes' warping of space-time offers an alluring pull.

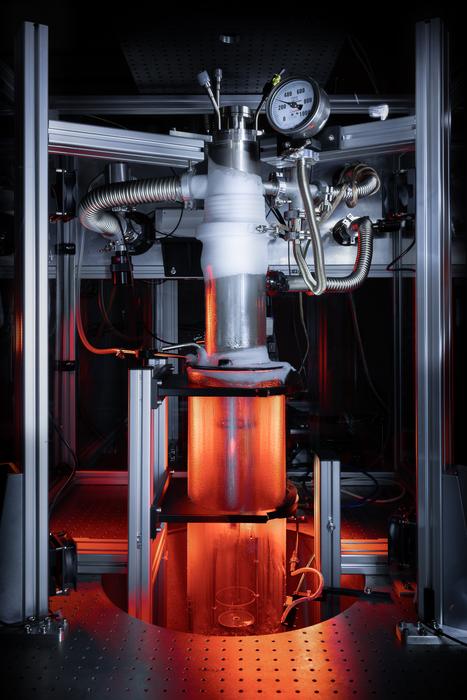

In the absence of a cataclysmic space-time rupture on Earth, the team behind the new study looked to a model system that could simulate some of the extreme eddies that exist around black holes. After supercooling liquid helium to a few fractions above absolute zero, they placed it inside a tank with a propeller at the bottom to stir up a vortex inside the fluid.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Then, by watching how the superfluid (which flows roughly 500 times more easily than water) moved, the researchers observed how thousands of tiny vortices inside it combined into a giant whirlpool.

"Superfluid helium contains tiny objects called quantum vortices, which tend to spread apart from each other," Svancara said in the statement. "In our set-up, we've managed to confine tens of thousands of these quanta in a compact object resembling a small tornado, achieving a vortex flow with record-breaking strength in the realm of quantum fluids."

By studying the quantum whirlpool, the scientists found convincing similarities to how black holes behave in space. Most notably, they observed a similar black hole phenomenon called ringdown, which is when a newly merged black hole wobbles on its axis.

Now that the simpler parallels have been observed, the researchers will train their experiment on more mysterious aspects of black hole behavior.

This "could eventually lead us to predict how quantum fields behave in curved spacetimes around astrophysical black holes," co-author Silke Weinfurtner, a professor of physics at the University of Nottingham, said in the statement.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus