Why physicists are determined to prove Galileo and Einstein wrong

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In the 17th century, famed astronomer and physicist Galileo Galilei is said to have climbed to the top of the Tower of Pisa and dropped two different-sized cannonballs. He was trying to demonstrate his theory — which Albert Einstein later updated and added to his theory of relativity — that objects fall at the same rate regardless of their size.

Now, after spending two years dropping two objects of different mass into a free fall in a satellite, a group of scientists has concluded that Galileo and Einstein were right: The objects fell at a rate that was within two-trillionths of a percent of each other, according to a new study.

This effect has been confirmed time and time again, as has Einstein's theory of relativity — yet scientists still aren't convinced that there isn't some kind of exception somewhere. "Scientists have always had a difficult time actually accepting that nature should behave that way," said senior author Peter Wolf, research director at the French National Center for Scientific Research's Paris Observatory.

Related: 8 Ways You Can See Einstein's Theory of Relativity in Real Life

That's because there are still inconsistencies in scientists' understanding of the universe.

"Quantum mechanics and general relativity, which are the two basic theories all of physics is built on today ...are still not unified," Wolf told Live Science. What's more, although scientific theory says the universe is made up mostly of dark matter and dark energy, experiments have failed to detect these mysterious substances.

"So, if we live in a world where there's dark matter around that we can't see, that might have an influence on the motion of [objects]," Wolf said. That influence would be "a very tiny one," but it would be there nonetheless. So, if scientists see test objects fall at different rates, that "might be an indication that we're actually looking at the effect of dark matter," he added.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Wolf and an international group of researchers — including scientists from France's National Center for Space Studies and the European Space Agency — set out to test Einstein and Galileo's foundational idea that no matter where you do an experiment, no matter how you orient it and what velocity you're moving at through space, the objects will fall at the same rate.

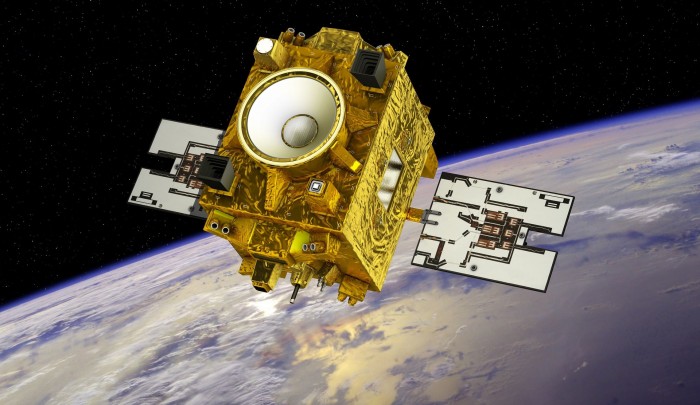

The researchers put two cylindrical objects — one made of titanium and the other platinum — inside each other and loaded them onto a satellite. The orbiting satellite was naturally "falling" because there were no forces acting on it, Wolf said. They suspended the cylinders within an electromagnetic field and dropped the objects for 100 to 200 hours at a time.

From the forces the researchers needed to apply to keep the cylinders in place inside the satellite, the team deduced how the cylinders fell and the rate at which they fell, Wolf said.

And, sure enough, the team found that the two objects fell at almost exactly the same rate, within two-trillionths of a percent of each other. That suggested Galileo was correct. What's more, they dropped the objects at different times during the two-year experiment and got the same result, suggesting Einstein's theory of relativity was also correct.

Their test was an order of magnitude more sensitive than previous tests. Even so, the researchers have published only 10% of the data from the experiment, and they hope to do further analysis of the rest.

Not satisfied with this mind-boggling level of precision, scientists have put together several new proposals to do similar experiments with two orders of magnitude greater sensitivity, Wolf said. Also, some physicists want to conduct similar experiments at the tiniest scale, with individual atoms of different types, such as rubidium and potassium, he added.

The findings were published Dec. 2 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

- Image: Inside the World's Top Physics Labs

- 18 Times Quantum Particles Blew Our Minds in 2018

- Twisted Physics: 7 Mind-Blowing Findings

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus