Cave thought to hold unicorn bones actually home to Neanderthal artwork

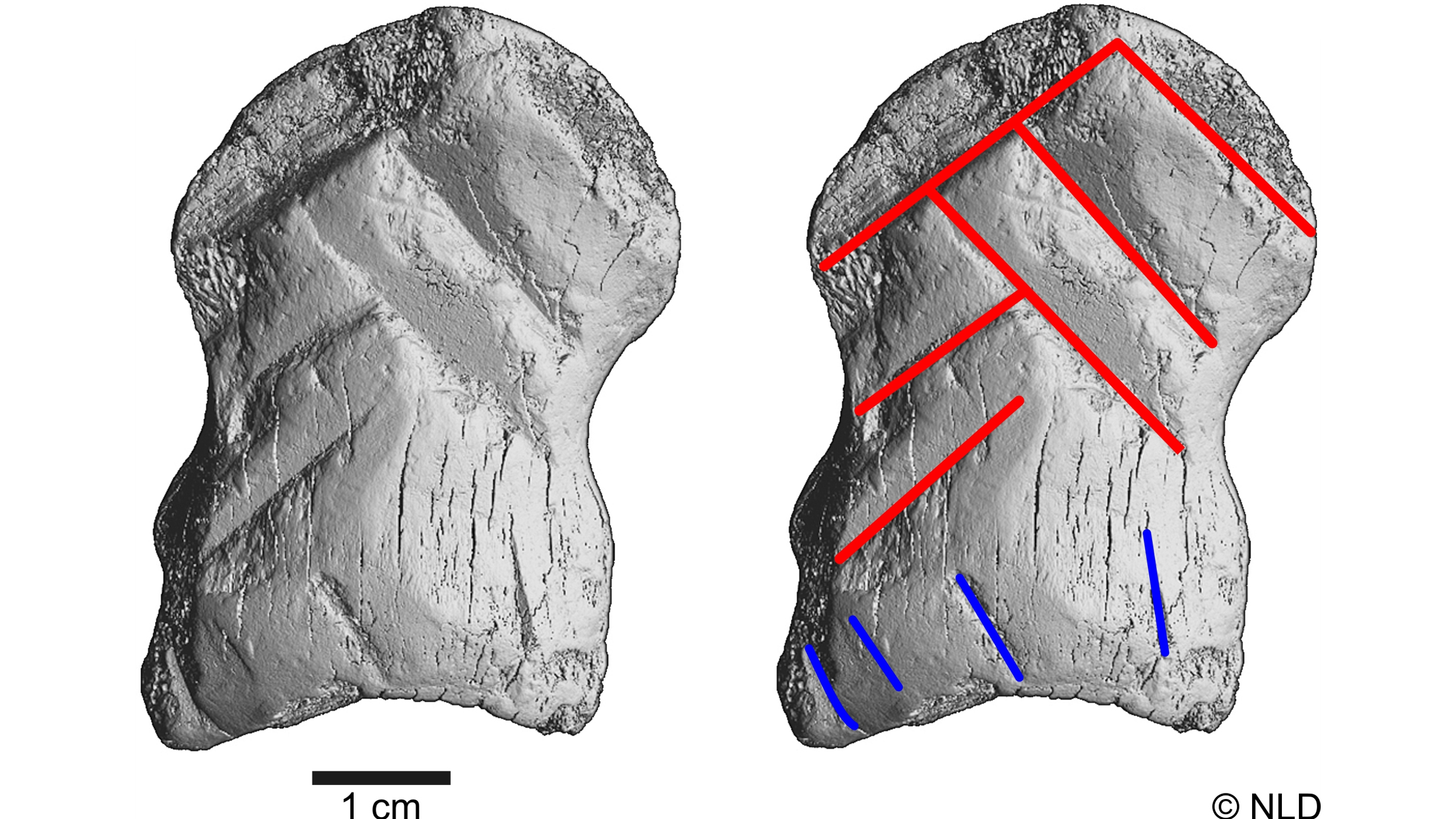

Neanderthals carved chevrons into a giant deer toe.

A German cave once famous for its "unicorn bones" during medieval times is home to a far-rarer non-mythical treasure: a piece of symbolic artwork created by Neanderthals, a new study finds.

The artwork, a chevron design, was carved into the toe bone of the now-extinct giant deer (Megaloceros giganteus), said the researchers. The team dated the bone to 51,000 years ago, a time when Homo sapiens hadn't yet ventured into the region, suggesting that the Neanderthals had carved the bone on their own, without influence or help from anatomically modern humans, the researchers wrote in the study, published online Monday (July 5) in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.

The symbolic artwork suggests Neanderthals had a greater cognitive capacity than previously thought.

"Neanderthals were very smart," study lead researcher Dirk Leder, an archaeologist at the State Service for Cultural Heritage Lower Saxony in Hanover, Germany, told Live Science. "They were able to communicate and express themselves by symbols. They were probably cognitively very similar to us as a human species."

Related: Photos: See the ancient faces of a man-bun wearing bloke and a Neanderthal woman

However, some archaeologists still have doubts that Neanderthals created symbolic art on their own. The recent discovery of an ancient Homo sapiens skull from Zlatý kůň in the Czech Republic had long segments of Neanderthal DNA, indicative of an interbreeding event more than 50,000 years ago, Silvia Bello, a researcher at the Centre for Human Evolution Research at the Natural History Museum, London who was not involved in either study, wrote in a perspective piece published in the same issue of Nature Ecology and Evolution.

"Given this early exchange of genes, we cannot exclude a similarly early exchange of knowledge between modern human and Neanderthal populations, which may have influenced the production of the engraved artifact from Einhornhöhle [cave in Germany]," Bello wrote in the piece. In other words, if Homo sapiens were in Central Europe earlier than thought, perhaps the Neanderthals learned about art-making from them, rather than coming up with it themselves.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Unicorn cave

The cave, known as "Einhornhöhle" (German for "unicorn cave"), has a storied history. Starting in medieval times, treasure hunters claimed to have found unicorn bones there, Leder said. "Of course, they were just cave bear bones, but they sold them as medicine or a remedy to pharmacies to turn a profit," he said.

In 1985, archaeologists found stone tools in the cave that were crafted by Neanderthals. To investigate more, Leder and his team returned in 2014. But it wasn't until 2019 that they discovered the carved toe bone, which lay buried near the cave's prehistoric but since-collapsed entrance. Initially, the scientists could see just one carved line on the bone, Leder said. It wasn't until excavators cleaned off the gritty silt, revealing the chevron design, that archaeologists knew they had something special.

The bone easily fits in a person's palm, measuring 2.2 by 1.6 inches (5.6 by 4 centimeters) in area with a thickness of 1.2 inches (3.1 cm). The 1.3-ounce (36 grams) object has 10 carved lines: Six make up the triangular chevron pattern and four run perpendicular to the bottom.

The lines were deeply carved, suggesting they weren't haphazardly-made butchering marks, and they were fairly evenly spaced, indicating that the bones had been "intentionally carved," Leder said.

Why the Neanderthals carved it, however, remains a mystery. The team investigated the bone with microscopy and micro-CT scans to see whether it had wear marks, Leder said. Such marks would indicate whether it was worn as a piece of jewelry, for instance as a pendant; but they found none, he said. However, the toe bone can stand on its own without falling over, so perhaps the Neanderthals placed it on its base as a display object, Leder said.

The engraved bone has "no practical use," the researchers noted in the study. It's small, curved and though it can stand on its own, it's not very stable, meaning the bone likely wasn't a chopping board or a processing surface. Instead, its precise geometric pattern, added to the fact that the giant deer was "a very impressive herbivore" and rarely seen north of the Alps at that time, suggests that it had symbolic meaning, the researchers wrote in the study.

As an experiment, Leder's team carved bones with 0.07-inch-deep (2 millimeters) lines. They did so by boiling cow toe bones and cutting and scraping them with flint blades, techniques that matched the ancient bone, according to a microscopic analysis. Each line required two blades (which quickly became dull) and took about 10 minutes, meaning that the six lines forming the chevrons could have been made in about 90 minutes, the researchers found.

Related: Denisovan gallery: Tracing the genetics of human ancestors

Is it symbolic?

Ancient sites used by Homo sapiens in Africa and Eurasia are awash with symbolic art, but similar evidence for Neanderthals is sparse and hard to interpret. For instance, Neanderthals used ochre, a red pigment, to paint various objects — animals, linear patterns, geometric shapes, hand stencils and handprints — in different Spanish caves more than 64,000 years ago, before modern humans arrived on the Iberian Peninsula, according to a 2018 study in the journal Science. However, some scientists dispute the age of the art, and say that while Neanderthals may have made line and dot drawings, it's debatable whether they created more complex artwork, such as animal drawings, on their own, Live Science previously reported.

In this case, the researchers argue that Neanderthals at Einhornhöhle carved this deer toe without input from Homo sapiens. Neanderthals lived in Europe between 430,000 and 40,000 years ago. The earliest evidence of Homo sapiens in Central Europe, in the upper Danube area, about 250 miles (400 kilometers) south, dates to 43,500 years ago, "several millennia after the engraved item from Einhornhöhle was deposited," the researchers wrote in the study. Direct influence from Homo sapiens to Neanderthals at Einhornhöhle is "improbable," they concluded, adding that "The cultural influence of H. sapiens as the single explanatory factor for abstract cultural expressions in Neanderthals can no longer be sustained."

Bello, in her accompanying perspective, writes that it's not such an open-and-shut case, given that genetic data suggests it's possible that Homo sapiens were in the area at that time. But even if the Neanderthals at Einhornhöhle did learn from Homo sapiens, "the capacity to learn, integrate innovation into one's own culture and adapt to new technologies and abstract concepts should be recognized as an element of behavioral complexity," Bello wrote. "In this context, the engraved bone from Einhornhöhle brings Neanderthal behavior even closer to the modern behavior of Homo sapiens."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.