Mixed-up sunspot emits powerful solar flare

Experts told Live Science that the resulting flare is impressive.

A mixed-up region of sunspots pointed almost directly at Earth has just emitted a major solar flare, which could cause havoc with power grids and communication networks over the next few days.

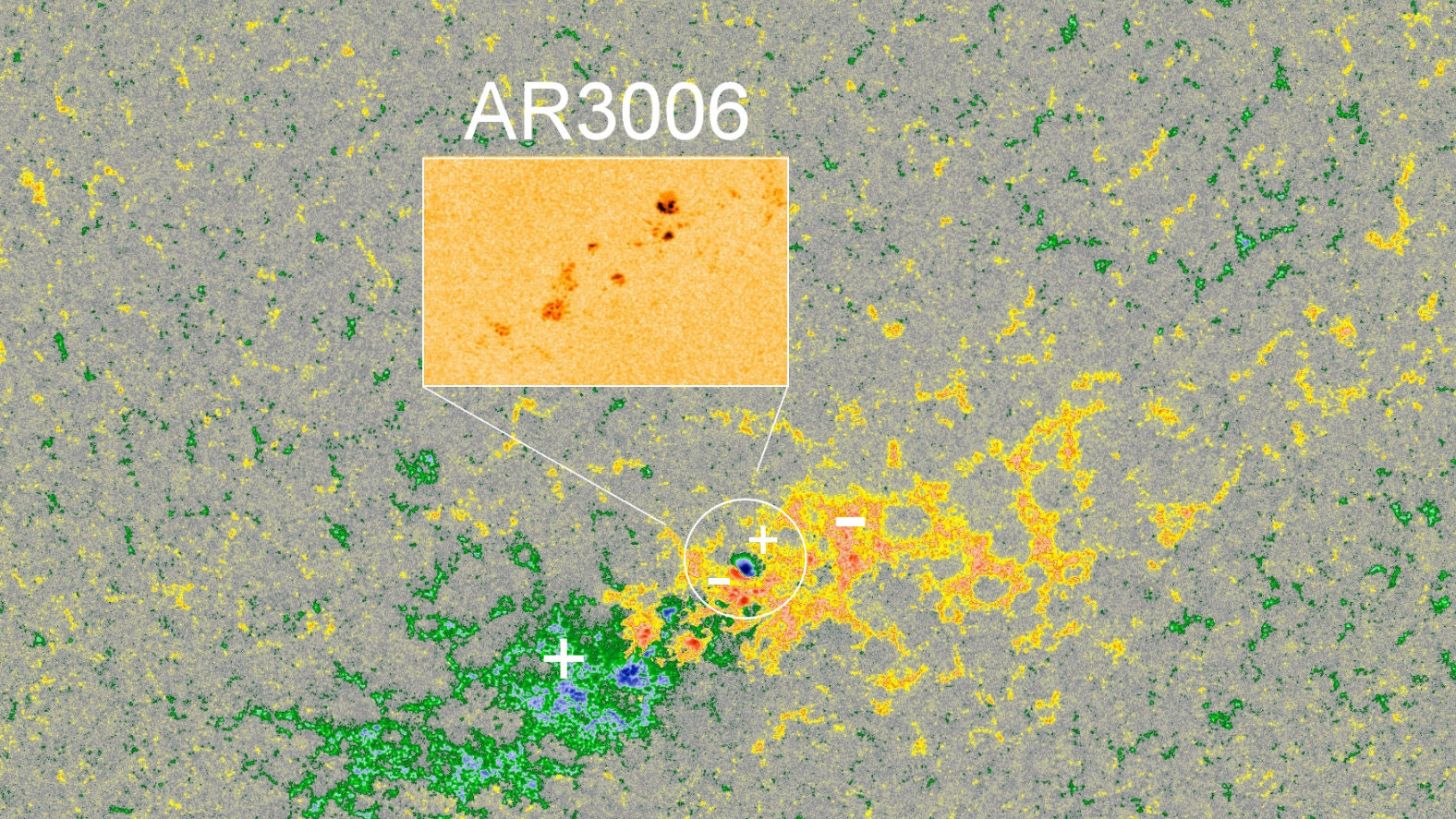

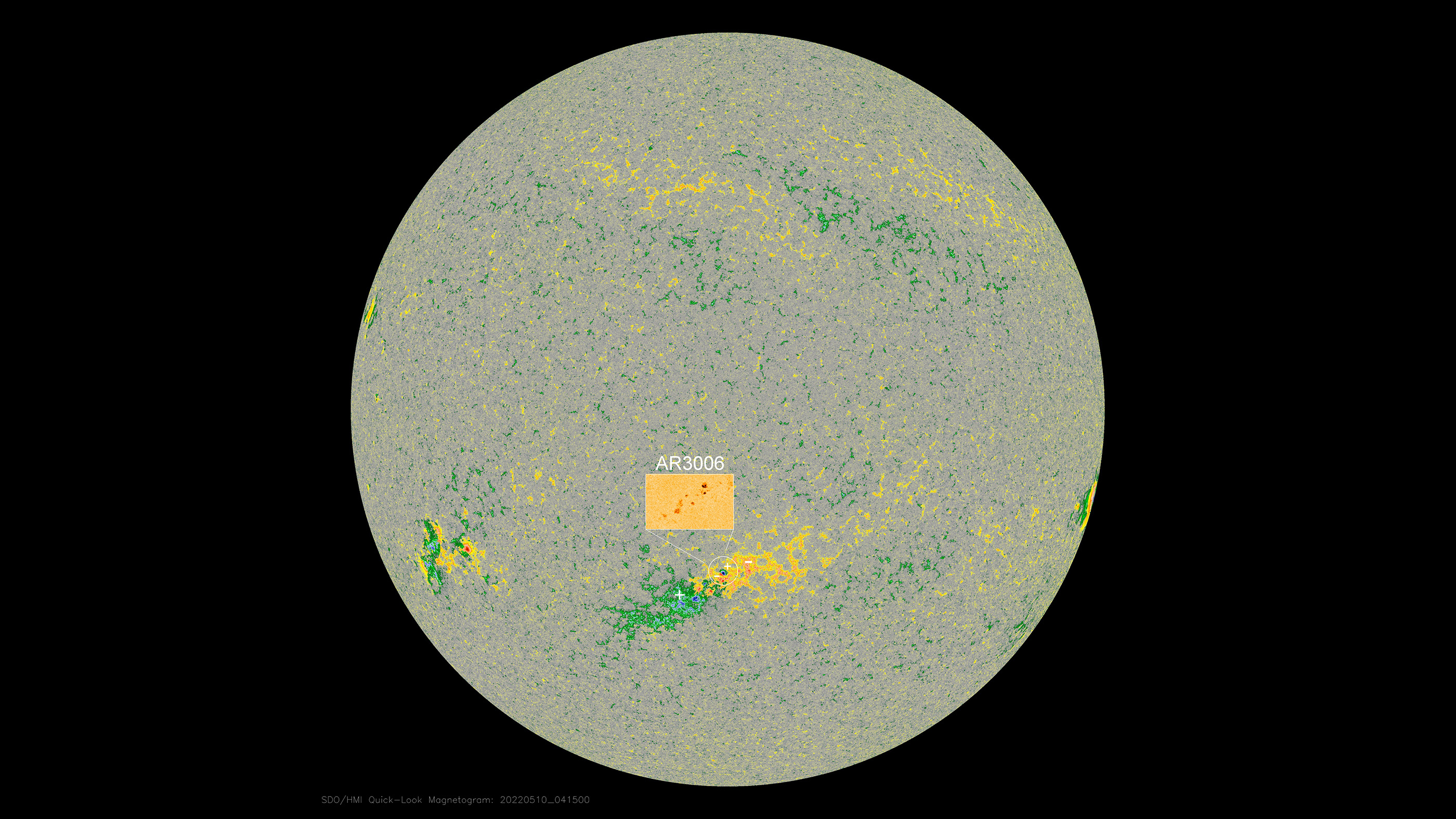

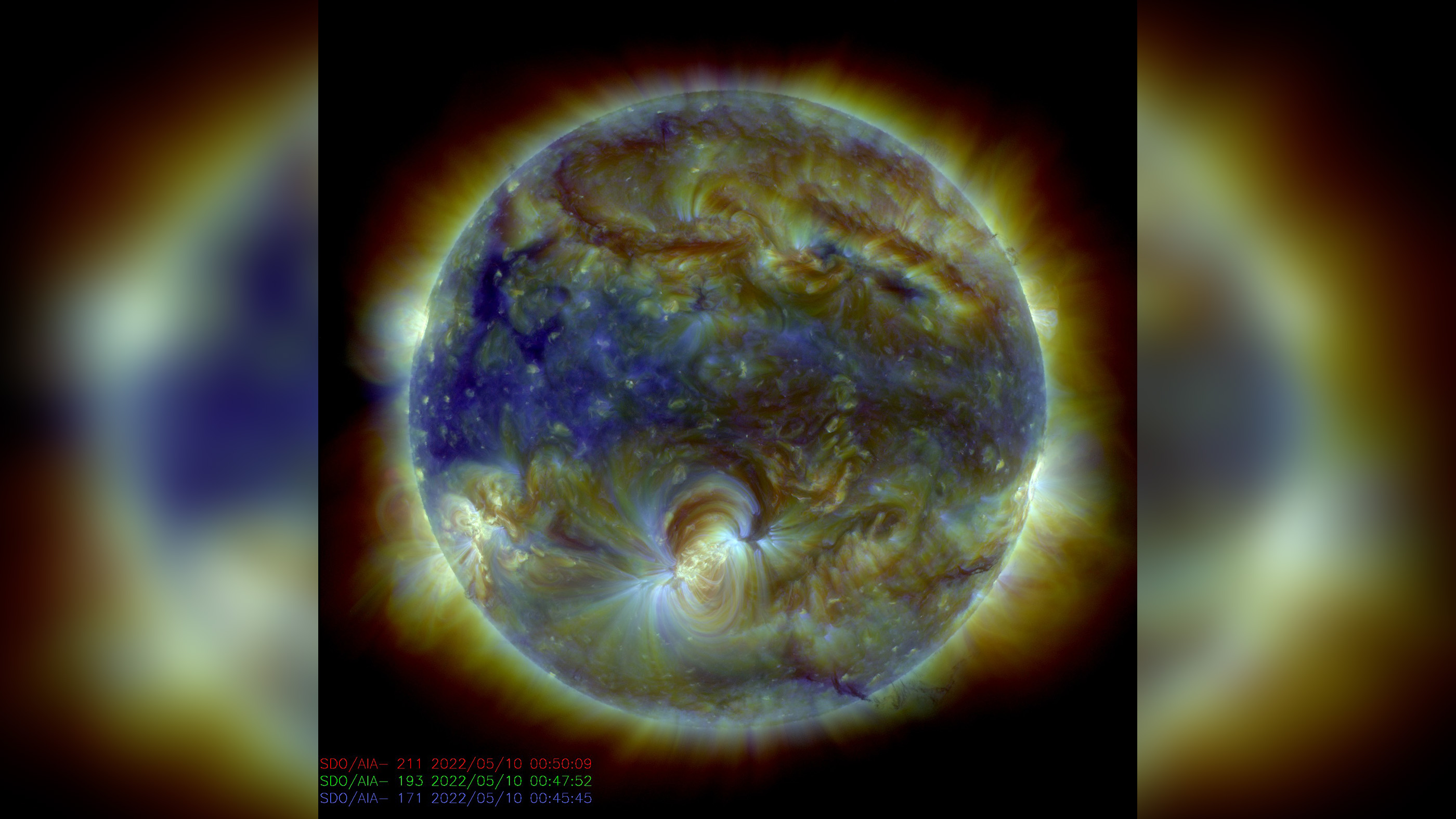

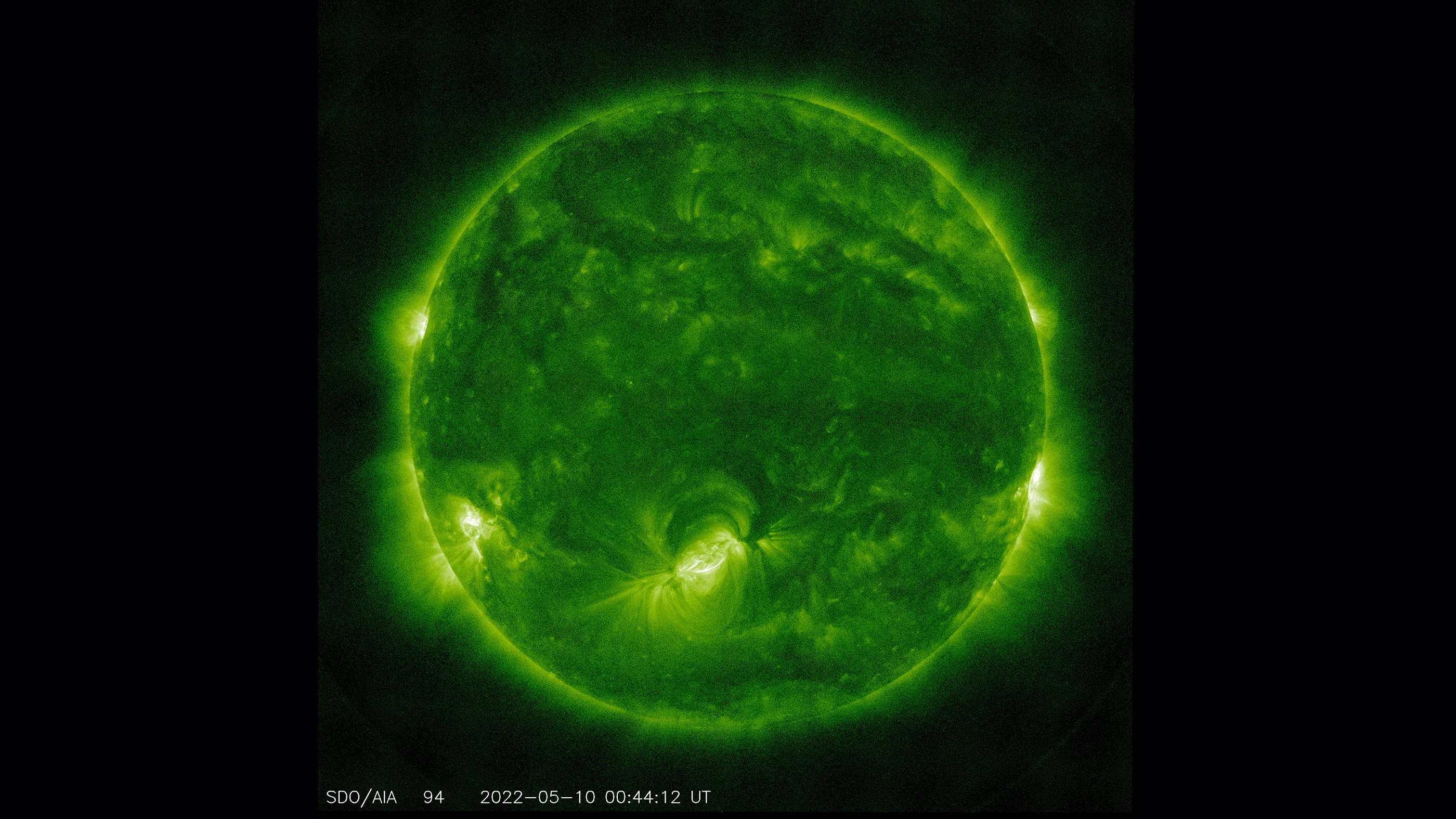

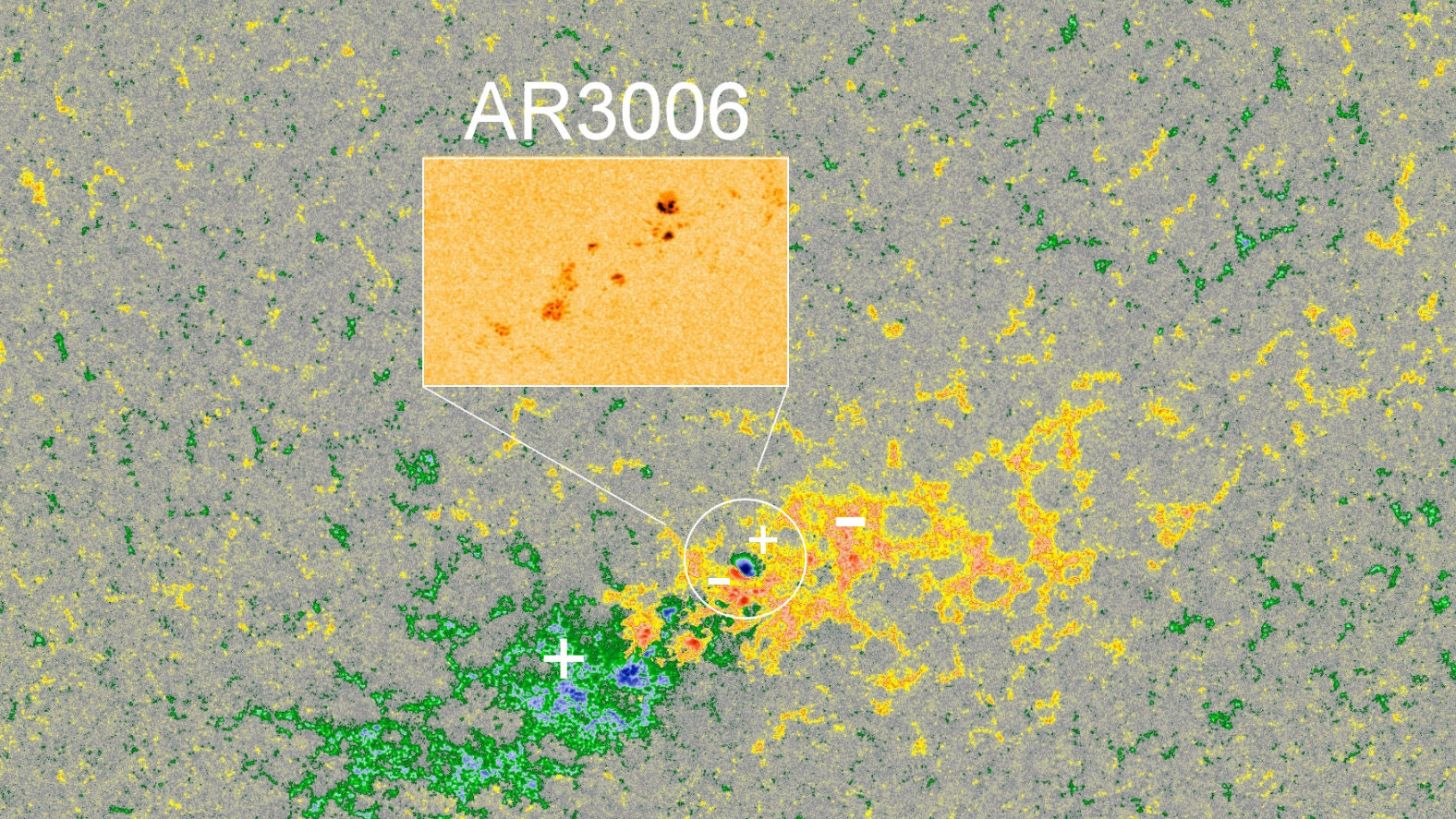

NASA's Solar Dynamic Observatory (SDO) first detected the sunspot area designated AR3006 ("AR" stands for "active region") several days ago; now the region is located near the center of the sun's visible disk.

SDO images show a spot near the region’s center has the reverse magnetic polarity of the surrounding area– meaning its magnetic field lines are pointing the opposite direction than the field lines nearby. This mismatch creates an unusual situation that can cause major disturbances, called "magnetic reconnections," when the areas of differing polarity interact.

And it now seems that interaction has happened. Earth-orbiting satellites have detected a radio burst indicating an X1.5 class flare erupted from AR3006 shortly before 9 a.m. ET (1400 Universal Time) on Tuesday (May 10). Experts told Live Science that the resulting flare is impressive, though not necessarily that unusual.

It's likely the flare also caused a coronal mass ejection (CME), launching a blob of plasma that could impact Earth in the next few days.

Related: Strange new type of solar wave defies physics

There are five classes of solar flare: A, B, C, M and X, according to NASA. Each is 10 times more powerful than the previous class, and they're followed by a number from 1 to 9 that indicates their strength within that class.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But there's theoretically no limit to the strength of the largest X-class flares: The most powerful on record, from 2003, overwhelmed the sensors at a classification of X28.

Coronal mass ejection

Jan Janssens, a communications specialist at the Solar-Terrestrial Centre of Excellence in Brussels – which coordinates international efforts to monitor the sun – called the new solar flare "impressive."

But "I'm a bit surprised by the strength of the flare, because all this concerned only small sunspots," Janssens told Live Science in an email.

AR3006 is a relatively small patch of sunspots developing in the remnants of a decaying active region, but its structure of mixed polarities means that it has a higher likelihood of snapping and releasing gobs of energy into space, he said.

Solar physicist Dean Pesnell of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, the project scientist for the Solar Dynamics Observatory, said the mixed polarity of the AR 3006 region was not uncommon.

"It happens when the twisted magnetic field lines flip around under the surface before erupting," Pesnell told Live Science in an email, adding that solar flares also seemed more common in regions with such complicated magnetic fields.

Tuesday's solar flare also caused a burst of radio waves that indicate it was accompanied by a coronal mass ejection (CME) of superhot plasma from the sun.

CMEs typically emit billions of tons of stellar material at speeds of hundreds of miles a second, according to the NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center.

If CME material from the latest flare impacts Earth in the next few days it has the potential to disrupt electricity grids and communications networks, and to damage satellites.

At the moment the sunspot region is pointed almost directly toward us, Janssens noted, but any risk of disruption from the CME will lessen over the next few days as AR3006 rotates towards the western edge of the sun's visible disk.

Pesnell explained that determining whether a CME would hit Earth was a "difficult and interesting calculation" that depends on the location and the dynamics of the CME filament. Whereas such events were "clues to how the solar dynamo operates," Pesnell said, "we only see the results of the dynamo, rather than the actual mechanism."

"It's like trying to understand the water cycle on Earth by only looking at the cloud tops and not knowing about the precipitation and oceans underneath," he said.

Magnetic fields

Sunspots are caused by magnetic disturbances in the sun's outer layer that expose the slightly cooler layer underneath. Even average sunspots are larger than Earth, and the biggest can be many times larger.

Although sunspots and solar flares occur more frequently near the peaks of the 11-year solar activity cycle, they're actually the result of a longer 22-year cycle in the polarity of the sun's magnetic fields.

The sun's magnetic fields become tangled as it rotates in space about once every 27 days, according to NASA. At the peak of a solar cycle, roughly every 11 years, the sun's fields become so tangled that the entire star abruptly reverses its magnetic polarity – the equivalent of Earth swapping its magnetic poles.

When that happens, sunspot activity declines as the tangled magnetic fields untangle again, until the sun has almost no sunspots at the lowest point of the solar activity cycle.

But the cycle starts again as the sun's magnetic fields start to become tangled again; and so it takes 22 years until the sun's magnetic polarity is the same as before.

Although it may seem like the sun was very active over the last few months, Live Science previously reported that its activity is about the same as during the last solar cycle, and even lower than it was at this time in the two cycles before that.

Records of the solar activity cycle began in 1775, and we're currently in the ascending phase of Solar Cycle 25; it's expected to peak in late 2024 or early 2025.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.