Lost fossil 'treasure trove' rediscovered after 70 years

Previous researchers were unable to record its exact coordinates.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Scientists have finally rediscovered a lost fossil site in Brazil, after the researchers who originally discovered it 70 years ago were unable to retrace their steps to the remote location. The unique geologic conditions at the long-lost site preserve paleontological treasures that could help shed light on one of the biggest extinction events in Earth's history.

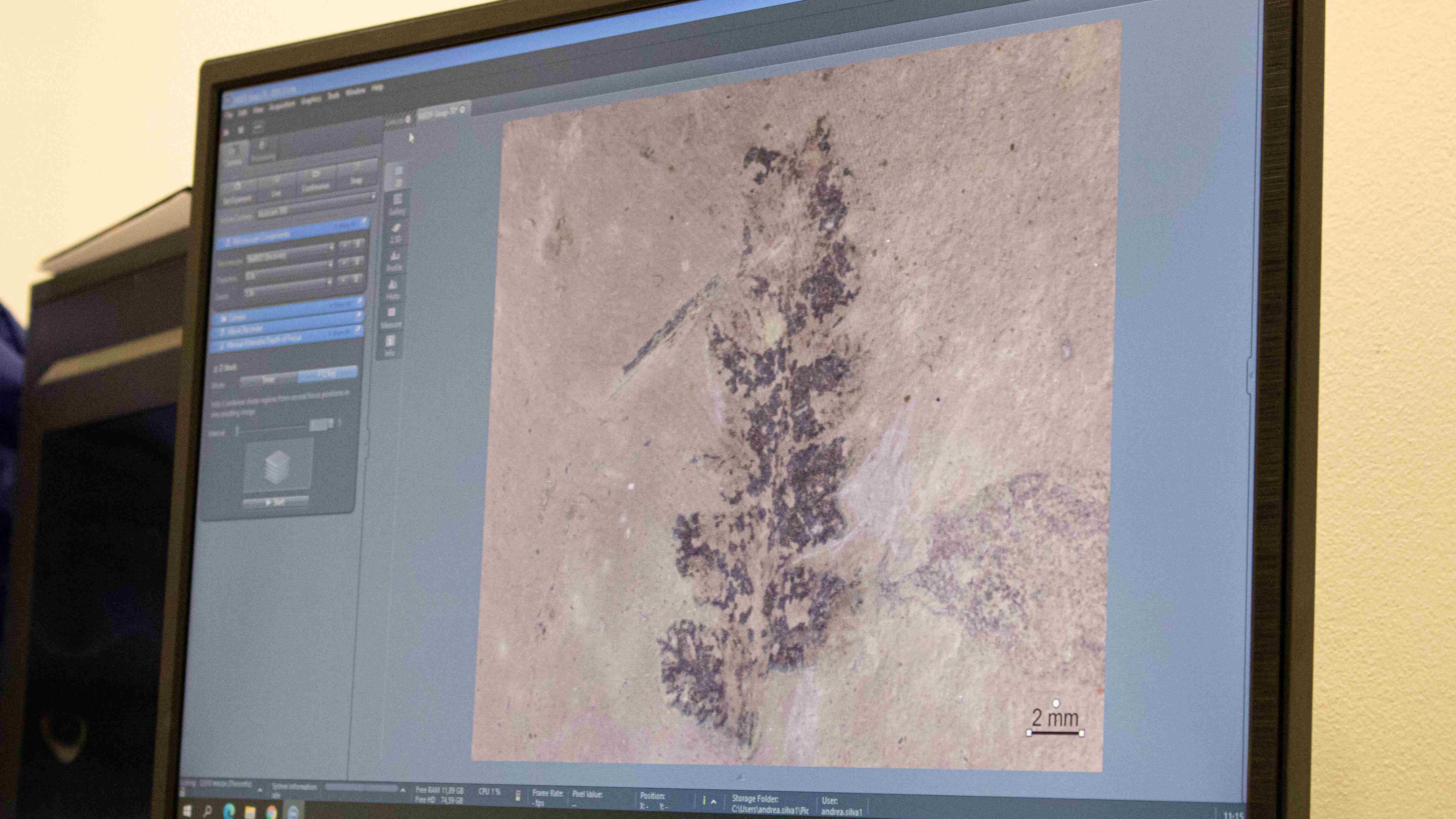

The rediscovered site, which is known as Cerro Chato, is located near Brazil's border with Uruguay in the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul. Around 260 million years ago, towards the end of the Permian period (299 million to 251 million years ago) conditions at the site were ideal for trapping and preserving dead organisms. As a result, multiple rocky layers at Cerro Chato are chock-full of delicate fossils — especially plants, which typically do not fossilize as well as animals do because they lack hard parts.

Paleontologists who first discovered Cerro Chato in 1951 were excited by its exceptionally well-preserved Permian remains. Unfortunately, without memorable landmarks or modern technologies, such as GPS, the researchers were unable to accurately record the exact geographical coordinates of the site, and when they attempted to return to the Permian treasure trove they could not find it. After several attempts to retrace their steps, the team gave up the search and declared the site lost. However, a new group of researchers took up the mantle and successfully found the lost location in 2019.

Related: 10 coolest non-dinosaur fossils unearthed in 2021

"For decades the geographic location of this outcrop was unknown," which inspired the new research team to conduct a massive "treasure hunt" to find it again, said Joseline Manfroi, a paleobotanist at the University of Vale do Taquari in Rio Grande do Sul, and co-author of a new study describing the rediscovered site. "Fortunately, after so long, we will have the opportunity to continue writing [the site's] history, through the fossil record," Manfroi said in a statement.

To date, more than 100 fossils — mostly plants, along with some fish and molluscs — have been uncovered at Cerro Chato by the original team and by the co-authors of the new study. Some of the fossilized plants are ancestors of modern-day conifers and ferns, the researchers reported.

However, the new team suspects that these fossils are just the tip of the iceberg. When the original researchers discovered the site, they were only able to scratch the surface of Cerro Chato’s fossil deposits before they lost track of its location, and though it was rediscovered almost three years ago, there's still a lot of ground to cover. "The area to be explored is huge," lead study author Joseane Salau Ferraz, a doctoral candidate at the Federal University of Pampa in Rio Grande do Sul, said in the statement. "I estimate that we haven't explored even 30% of all available space."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The plant fossils at Cerro Chato could help researchers understand more about drastic climate change that took place toward the end of the Permian, which triggered an extinction event that wiped out around 90% of life on Earth. "The fossils we are studying are of global importance, as they are direct testimonies of the environmental changes that took place during the Permian period," Ferraz said. "These studies will help us to retrieve information about the distribution of these plants around the world."

The team published its findings online May 15 in the Brazilian Society of Paleontology's journal Paleodest, and the study is available to download for free in English and Portuguese. "We chose to publish the article in Portuguese precisely to make the text available to the local population," Ferraz said. "They are very excited about paleontology, which is cool to see."

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus