Just over a year after its historic launch, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is challenging astronomers’ expectations of the early universe and showing that massive galaxies likely formed much earlier than predicted.

JWST sees in the far infrared part of the electromagnetic spectrum that is invisible to our eyes, according to NASA. This means that the telescope is optimized to capture light from the early universe, which has been stretched out towards these longer and redder wavelengths as the universe has expanded over time — a process known as redshifting.

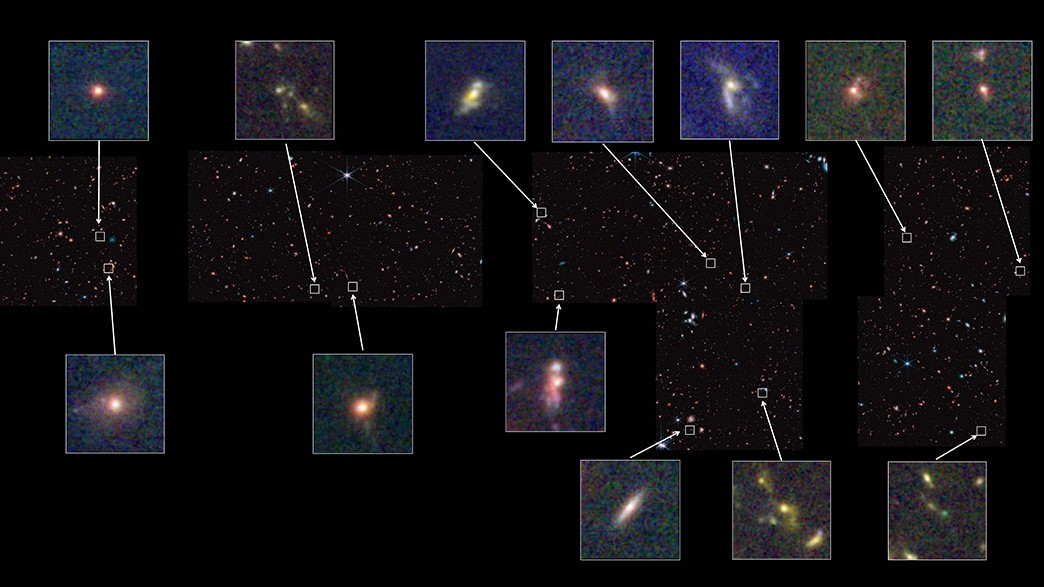

Galaxies can come in a variety of types, including beautiful spiral galaxies like our own Milky Way, as well as elliptical or irregular types, astronomer Jeyhan Kartaltepe of the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York said during a press conference at the 241st meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle, Washington.

The Hubble Space Telescope had already spotted all the different types of galaxies as far back as 11 billion years ago, suggesting that their formation had occurred even earlier, she added. Some researchers thought that JWST might finally glimpse these early stages of galaxy formation because the telescope sees further back in cosmic history than Hubble, Kartaltepe said.

She and her team analyzed 850 galaxies between 11 and 13 billion years ago, classifying them according to whether they were spirals, ellipticals, irregulars or some combination of the three. They found that the percentage of each galaxy type remained roughly the same as in the modern universe throughout that time period.

This indicates that galaxies were already fairly mature even at this stage in cosmic history, Kartaltepe said. “We’re really not seeing the earliest formation of galaxies yet,” she added. Her team’s findings have been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal, according to the Rochester Institute of Technology.

The oldest galaxies in the universe?

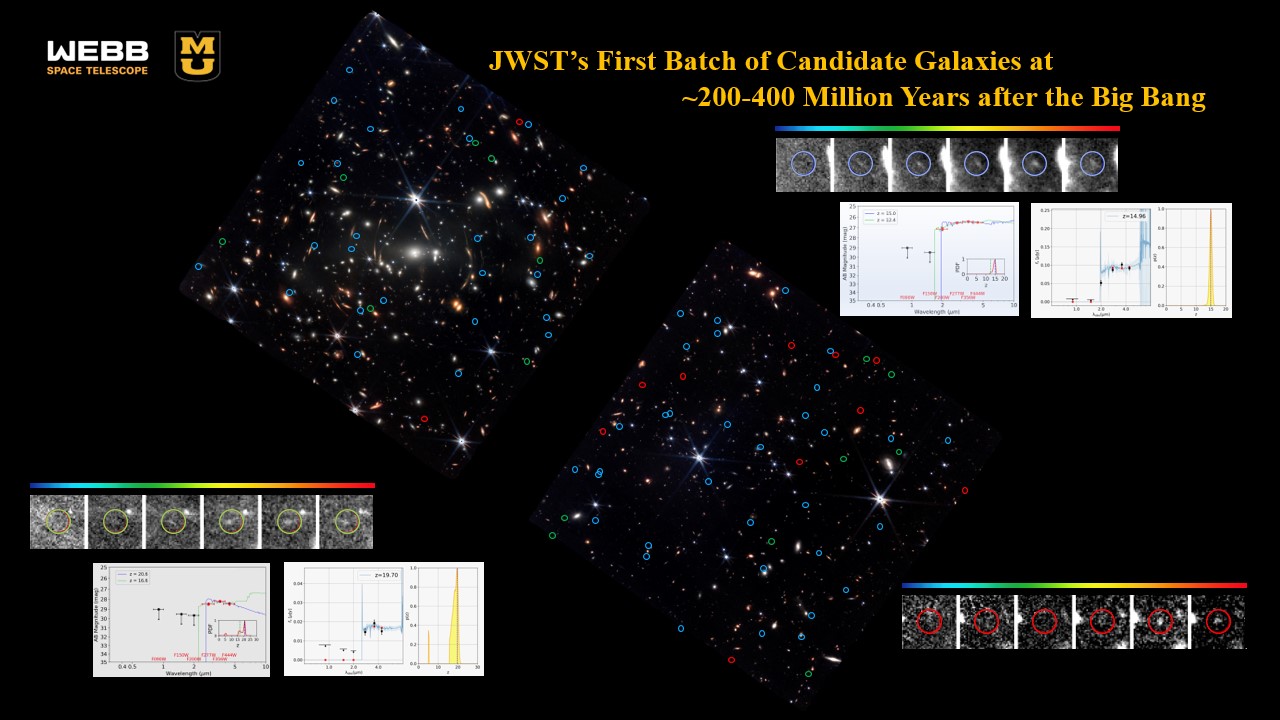

Another puzzling view of the early universe came from astronomer Haojing Yan of the University of Missouri. He and his colleagues looked at one of JWST’s first snapshots — a field of stars, galaxies and galactic clusters known as SMACS 0723 — and pinpointed some of the oldest galaxies ever observed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Yan’s team identified 87 galaxies in this field that might have been present a mere 200 to 400 million years after the big bang, an extremely early epoch to see so many galaxies. Further analysis will be needed to confirm that these primordial galaxies are actually located at such early times, but Yan said he’d “bet 20 bucks and a beer” that at least half will end up being correctly placed in such ancient days.

While many researchers thought JWST would find at least a handful of galaxies so far back in cosmic history, few expected that it would turn up so many, Yan added. “Even if just a small fraction turn out to be real,” he said, “then our previously-favored picture of galaxy formation in the early universe must be revised.”

Yan declined to speculate what might have caused galaxies to form much earlier than predicted in the universe, but he said that it is now up to theorists to come up with plausible explanations for such observations. His team’s work appeared in the Astrophysical Journal in December.

'Green peas' from the dawn of time

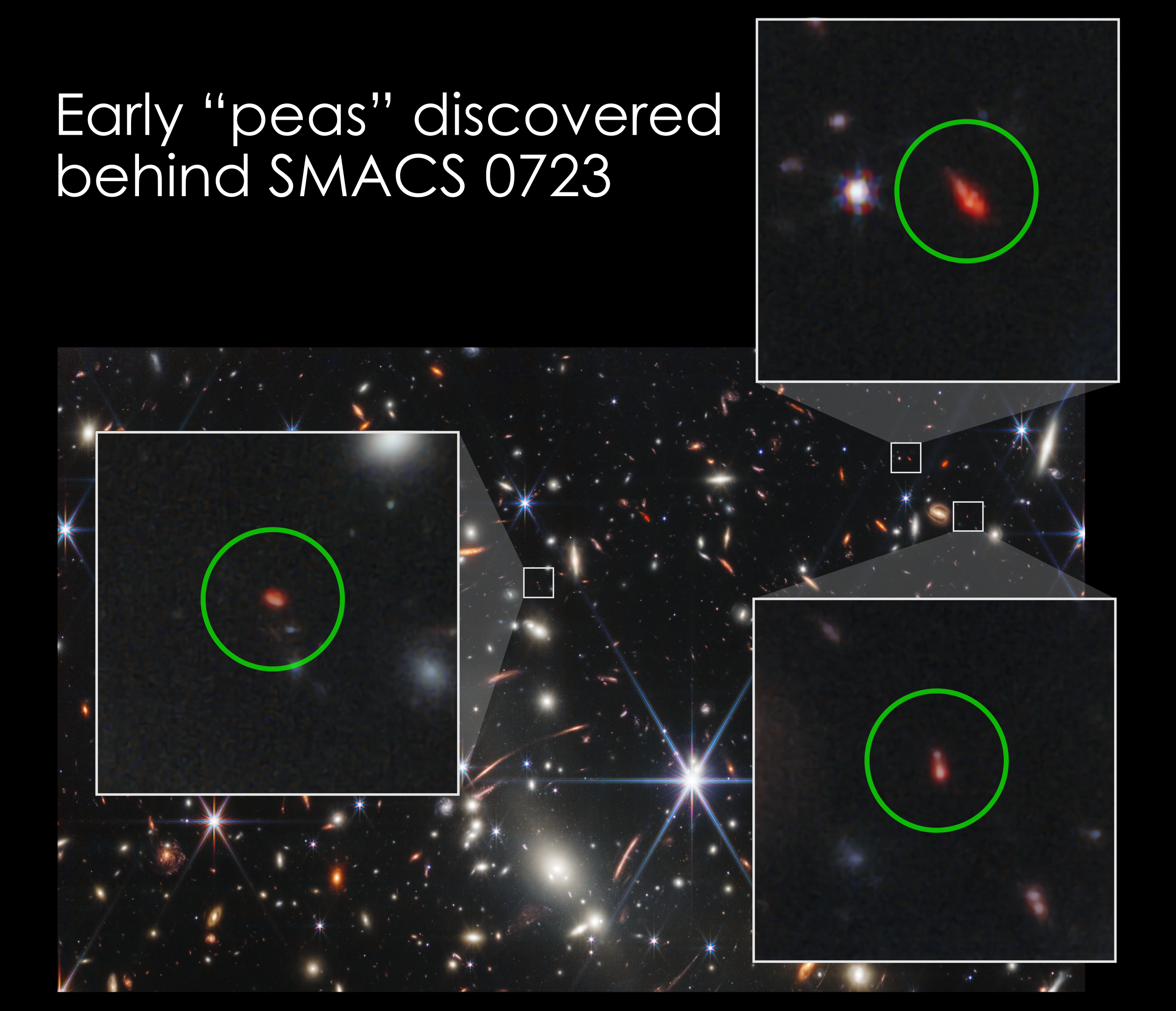

Astrophysicist James Rhoads of NASA’s Goddard Spaceflight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland offered one final look at the early universe during the AAS press conference. Also analyzing JWST’s SMACS 0723 deep field image, he and his colleagues identified three tiny galaxies whose chemical compositions very closely match a rare type of galaxy nicknamed “green peas.”

First spotted by citizen scientists working with the Galaxy Zoo collaboration in 2009, green pea galaxies are very small — roughly 5,000 light-years across, or only a 20th the size of the Milky Way — and are home to a great deal of star formation, Rhoads said.

Green peas are rare, making up only 0.1%of all nearby galaxies, and are very pristine, according to NASA. As stars burn hydrogen and helium, they form heavier elements like oxygen and carbon, and in their death throes they spew such elements across a galaxy. But green peas have very low levels of heavier elements, containing roughly a fifth of the oxygen of the Milky Way, similar to the three objects JWST spotted.

“We found what may be the most chemically primitive galaxies,” Rhoads said during the press conference, adding that astronomers can use their modern counterparts to study these ancient outliers and learn more about the early universe. The findings appeared Jan. 3 in the Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Rhoads suggested that the modern green pea galaxies may be “a bit like living fossils of early galaxy formation. Coelacanths, if you will,” referring to a type of fish once thought to be extinct until it was found off the coast of South Africa in 1938.

Adam Mann is a freelance journalist with over a decade of experience, specializing in astronomy and physics stories. He has a bachelor's degree in astrophysics from UC Berkeley. His work has appeared in the New Yorker, New York Times, National Geographic, Wall Street Journal, Wired, Nature, Science, and many other places. He lives in Oakland, California, where he enjoys riding his bike.