Webb Telescope is now orbiting 1 million miles from Earth

The telescope launched from Kourou, French Guiana on Dec. 25.

The most powerful space telescope ever launched just fired its thrusters to reach its permanent cosmic address. With this final course adjustment complete, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is now orbiting around the sun at a distance of nearly 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth.

Around 2 p.m. EST on Monday (Jan. 24), ground operators guided the telescope through a final mid-course correction burn, fine-tuning JWST's final orbital position for its science mission, NASA representatives announced in a briefing.

For approximately five minutes, the team fired JWST's station-keeping thruster to gently nudge the observatory into place without overshooting its destination; by comparison, the "big burn" course correction that was performed with a different thruster on Dec. 25 was for a much more dramatic maneuver and lasted over 60 minutes, Keith Parrish, JWST Observatory Manager at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in Greenbelt Maryland, said at the briefing.

Related: Building the James Webb Space Telescope (photos)

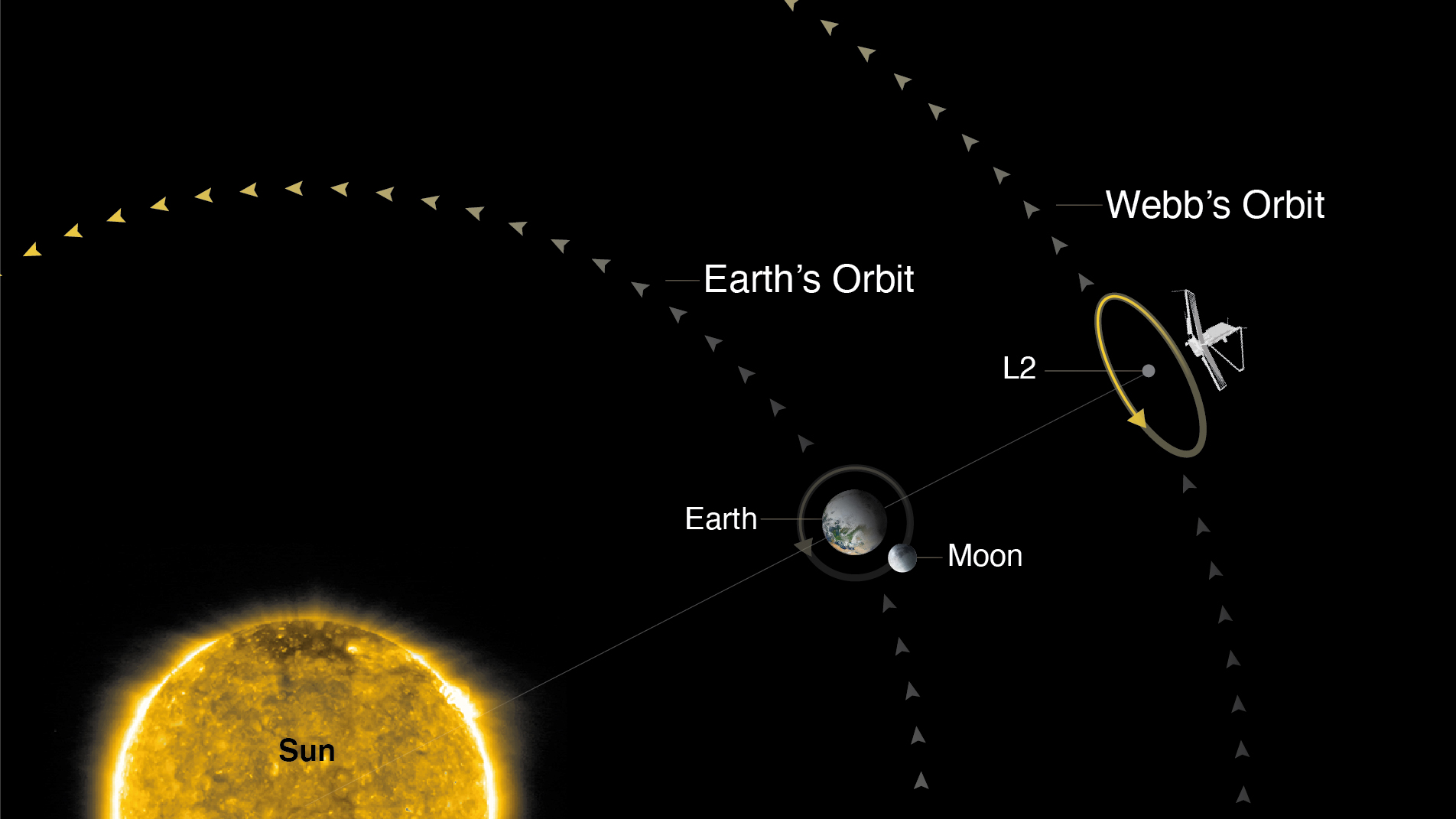

When the $10 billion Webb Telescope launched on Dec. 25, 2021, it blasted off from South America on Earth's sun-facing side and followed a curved trajectory to reach its destination, known as the second Lagrange Point, or L2. There are five Lagrange Points around Earth and the sun; objects at these positions rest in a gravitational equilibrium, where the pull of gravity and centrifugal force from the object's orbit "park" its body in place, according to NASA.

"The way I see it in my head is like a Pringles potato chip," Jane Rigby, JWST Operations Project Scientist, said at the briefing. In the potato chip scenario, Webb is perpetually inching up one side of a curved chip and then gently falling back down and traveling up the other curving side, repeating the movement over and over again "for the life of the mission," Rigby said.

As Webb orbits the sun from this spot, it will also orbit around L2 about once every six months, in what is known as a halo orbit. This orbit will keep the telescope in the same position relative to Earth and the sun, and it will ensure that the sun won't be eclipsed by Earth (from the telescope's perspective) which could affect the thermal stability of Webb's instruments and hamper its access to solar power, NASA representatives said in a statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Webb's operators will continue to tweak the telescope's orbit around L2 by briefly firing its thruster about once every 21 days, according to the NASA briefing. But even with those frequent, small adjustments, Webb's fuel reserves should far exceed the anticipated 10-year mission length. In fact, Webb may even have enough fuel to keep going for 20 years, Parrish said.

With JWST now orbiting L2, the telescope — a collaboration between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) — will undergo more tests and alignments over the next several months, in preparation for conducting science observations that will target some of the faintest and most distant objects in the universe.

Webb successfully reached other significant milestones earlier this month. On Jan. 1, the telescope unfurled its enormous sunshield, a critical component for keeping its instruments cold as they search for faint signals from the early universe, Live Science sister site Space.com previously reported. Webb's giant gold mirror segments then unfolded from their launch positions on Jan. 8, according to NASA. Over the next three months, engineers will align the telescope's primary mirror by aiming its 18 mirror segments at a bright isolated star, lining up and stacking those images, and then aligning the mirror segments to about 1/5000 of a human hair, so that they act as "a single monolithic mirror," Lee Feinberg, JWST's Optical Telescope Element Manager at GSFC, said at the briefing.

"The last 30 days, we called that '30 days on the edge,' and we're just so proud to be through that," Parrish said. "But on the other hand, we were just setting the table. We were just getting this beautiful spacecraft unfolded and ready to do science, so the best is yet to come."

Webb won't be Earth's only set of eyes in space; its predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope, is entering its third decade of capturing spectacular space images from its orbital path around Earth, at a distance of about 340 miles (547 km). Hubble's images continue to present new insights about the cosmos; recent Hubble observations of the dwarf galaxy Henize 2-10, located about 34 million light-years from Earth, revealed clues that black holes may play a part in star formation, Space.com previously reported.

However, Webb's infrared equipment and its much larger primary mirror — at 21.3 feet (6.5 meters) wide, it's the biggest ever sent to space — will offer unprecedented views of cosmic objects over the course of its mission, according to the ESA. Webb will use infrared to detect faint signals from the universe's earliest stars and galaxies, and to penetrate the dense dust clouds that shroud the formation of stars and planets, according to NASA.

"Everything we're doing is about getting the observatory ready to do transformative science," from exploring the atmospheres of planets orbiting other stars to studying the darkest parts of the sky for signs of first-generation galaxies that formed more than 13.5 billion years ago, Rigby said. "We're a month in and the baby hasn't even opened its eyes yet, but that's the science that we're looking forward to."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus