Short-necked giraffe relative discovered in China. It used its helmet head to bash rivals.

The animals lived 16.9 million years ago.

Nearly 17 million years ago, a relative of modern giraffes that roamed northern China sported a thick, stumpy neck and a thick skull — perfect for sparring with rival males in headbutting battles.

The newly-discovered giraffe relative, a now-extinct species named Discokeryx xiezhi, also had a bony, disk-like shield on the top of its skull, covered in a protective layer of keratin — the same type of tissue found in the horns of headbutters such as bulls and rams. The hard disk resembled a sort of squat helmet that sat atop the animal's head, scientists reported in a new analysis of several D. xiezhi fossils, published June 2 in the journal Science.

D. xiezhi likely bashed their "helmets" together during fights over mates, just as modern male giraffes fight over females by violently thwacking their necks together, using a combat style known as "necking," the researchers concluded.

"[The researchers] have provided unequivocal evidence that the Discokeryx fossil is beautifully adapted to intense head clashes," said Robert Simmons, a honorary research associate at the University of Cape Town's FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, who was not involved in the study. This trait must be sexually selected "since head-to-head clashes are intimately involved in male-male combat," Simmons told Live Science in an email.

Related: Adorable dwarf giraffes spotted for the first time

In other words, intense competition over mates likely drove D. xiezhi to evolve its thick neck and inbuilt helmet. Simmons and other scientists have also hypothesized that sexual competition drove the modern giraffe to evolve its long neck and ossicones, or the bony projections that stick off its head; this idea is known as the "necks-for-sex" hypothesis.

Built for headbutting

The researchers uncovered the newly-described D. xiezhi fossils in the Junggar Basin, a large sediment-filled depression in the Xinjiang region of northwestern China. One specimen included a complete braincase — the part of the skull that houses the brain — and the first four vertebrae of the animal's spine.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These spinal bones, known as cervical vertebrae, are quite massive "because they, along with the skull, were used for headbutting," said study author Jin Meng, a vertebrate paleontologist and the curator-in-charge of fossil mammals at the American Museum of Natural History. Each neck bone "is very robust, very thick, in terms of the cross-section, so it can take this kind of impact," he told Live Science.

Two of the D. xiezhi specimens included teeth with "relatively high crowns," suitable for munching on grasses, the researchers reported. Based on the shape of the teeth and the isotopes — element variants with different numbers of neutrons — in their enamel, the team concluded that the creature was likely an open-land grazer that changed up its habitat depending on the season.

Based on the sizes of all the fossils, the team thinks that D. xiezhi stood about as tall as a modern sheep and had a neck of similar length to other comparably-sized land mammals, Meng told Live Science. And based on analysis of the fossilized bones and teeth, the team determined that this stocky, extinct animal, though related to the towering giraffes of today, is not a direct ancestor of living giraffes.

"It's a different branch of the tree of the giraffe family," Meng said.

Related: 10 coolest non-dinosaur fossils unearthed in 2021

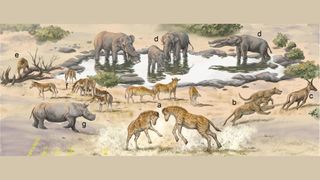

The team then compared the bones to those of living giraffes and their extinct relatives. In this group, they identified 14 different types of "headgear," including the ossicones of modern giraffes and the helmets of D. xiezhi, for example. Along with this wide variety of headgear, they noted an array of head and neck shapes, and in particular, they found that the animals' uppermost vertebrae dramatically varied in length and thickness.

Just as D. xiezhi seems built for head-butting and modern giraffes for necking, all these giraffe relatives may have evolved their unique headgears and necks, in part, to suit their specific combat styles, the team wrote in the study. This aligns with the necks-for-sex hypothesis for modern giraffes, which suggests that at some point in evolutionary history, males with long, sinewy necks dominated in fights for females. Over time, their reproductive success drove the species to evolve longer and longer necks.

Simmons and Lue Scheepers, a zoologist at the Etosha Ecological Institute in Namibia, first introduced the necks-for-sex idea as co-authors of a 1996 paper, published in the journal The American Naturalist. At the time, their hypothesis contradicted the established idea of how giraffe necks evolved. Charles Darwin famously proposed that giraffes evolved long necks due to competition over food; by being ridiculously tall, the animals could consume foliage that remained out of reach to other animals. Even today, the debate continues over whether giraffe necks evolved mostly due to competition over subsistence or sex, according to National Geographic.

But in all likelihood, giraffes' extreme necks were probably shaped by both evolutionary pressures, to some degree, Simmons told Live Science.

"At present, it is not easy to distinguish the 'feeding competition' hypothesis from the 'necks for sex' idea," Simmons said. "It is very likely that both have played a role in the evolution of the magnificent animals we see today." The discovery of short-necked D. xiezhi doesn't settle the necks-for-sex debate, but in the future, the detection of more ancient giraffoid fossils could help clarify how modern giraffes came to look the way they do, he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Most Popular