Deep-sea sponges caught 'sneezing' in time-lapse photos

Deep-sea sponges may not have noses, but they still sneeze.

To the naked eye, deep-sea sponges seem to sit totally still, confined to one spot on the ocean floor. But in reality, the squidgy creatures move quite a bit and sometimes let out mighty "sneezes" by contracting their entire bodies at once.

You may miss your chance to say "gesundheit," though, because sponge sneezes happen in slow motion, according to a recent study.

Researchers at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) caught the behavior on camera using time-lapse photography, according to a statement describing the study. Their cameras sit some 2.5 miles (4,000 meters) below the ocean's surface, at a long-term study site called Station M, situated about 136 miles (220 kilometers) off the central California coast. While perusing old time-lapse photos of the seafloor, one researcher caught sight of something unexpected.

"Everyone was watching sea cucumbers and urchins snuffling around on the seafloor, but I watched the sponge. And then the sponge changed size," lead author Amanda Kahn, a former MBARI postdoctoral scholar, said in the statement.

Related: Six bizarre feeding tactics from the depths of our oceans

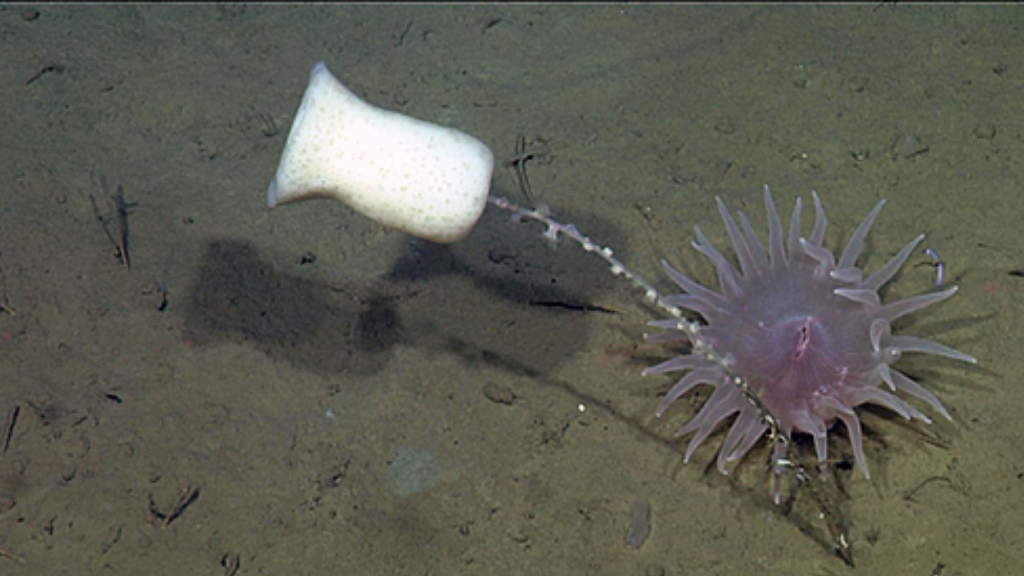

Kahn and her co-author Clark Pennelly, an atmospheric researcher at the University of Alberta, took a closer look at the images and found that several glass sponges, which stick up from the seafloor like tulips, seemed to contract and expand in a rhythmic pattern over time. The researchers saw similar movements from sputnik sponges, which periodically unfurled and retracted their "parasol-like" filaments in the surrounding water. "It's not yet known what the timing of those rhythms are or why they happen the way they do," Kahn added.

Sponges typically filter nutrients from the water for nourishment, and previous research suggested that the creatures cannot filter feed as efficiently when they contract their bodies, according to the statement. Co-author Sally Leys, a professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Alberta, has observed similar behavior in freshwater sponges, which can become irritated by particles circulating in the water and contract to push the contaminated liquid from their bodies — similar to how we rid our mouths and noses of dust when we sneeze.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A freshwater sponge can take about 40 minutes to complete a single sneeze, according to the MBARI statement. In the new footage, sneezes took hours or even weeks to complete. "The deep sea is a dynamic place, but it operates on a different time scale … than our world," Kahn said.

The study was first published Jan. 2 in the journal Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography. A finalized version of the paper will appear in a special issue of the same journal this summer.

- Sea science: 7 bizarre facts about the ocean

- The 10 weirdest sea monsters

- The world's biggest oceans and seas

Originally published on Live Science.

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus