Church of the Holy Sepulchre's mysterious 'graffiti' crosses may not be what they seem

It's likely that pilgrims didn't carve these crosses.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Thousands of tiny, "medieval" crosses carved into the walls of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem have been misunderstood for years, new research suggests.

Until now, religious scholars thought that medieval pilgrims traveling to the sacred site carved the crosses as a type of holy graffiti. But new research indicates that just a handful of people — likely masons or artisans — carved the crosses, probably on behalf of pilgrims, who may have kept the dust from each carving as a relic or sacred souvenir. Some of the crosses date to the 14th or 15th centuries — hundreds of years after the Crusades in the Holy Land (1096-1291), indicating that post-medieval pilgrims likely had the crosses made.

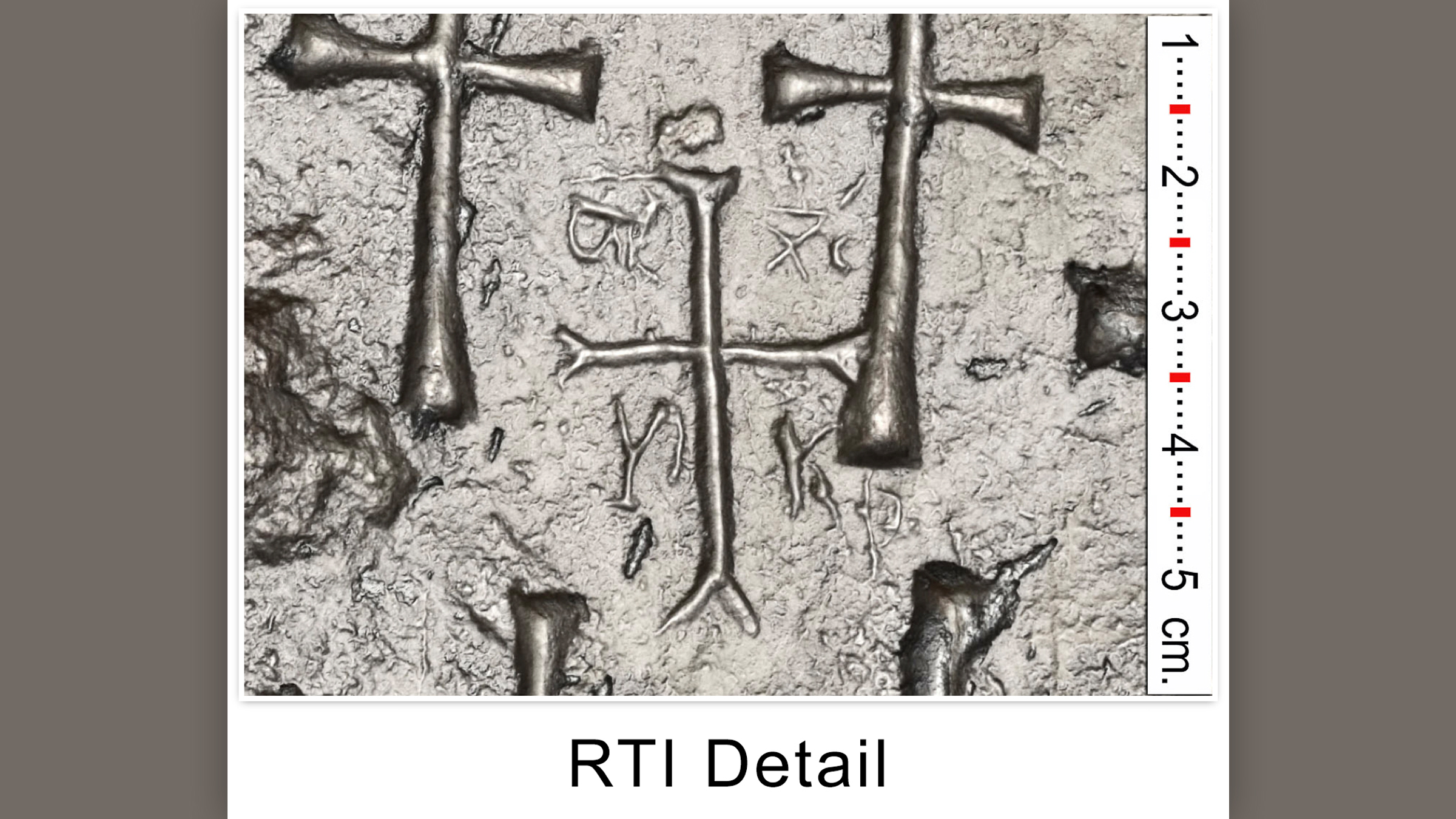

During the research, "we managed literally to dive inside those crosses, to scrutinize, to analyze every millimeter inside the crosses — their depth, their width, even the hands of the men who carved them," project leader Amit Re'em, Jerusalem regional archaeologist with the Israel Antiquities Authority, told Live Science. "And it was the same person, or several persons, that were responsible for doing [these crosses], not the hundreds and thousands of the pilgrims who visited the church."

The findings, which have yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, were presented at the 2018 Electronic Visualisation and the Arts in London.

Related: Photos: 1st-century house from Jesus' hometown

Re'em got the idea for the study while visiting the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The church was built in the fourth century, when St. Helena, the mother of Roman Emperor Constantine the Great, traveled to Jerusalem, and according to legend, she helped discover where Jesus had been crucified, buried and resurrected. Constantine had a basilica built there, and it later became known as the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

One day, when Re'em was looking at the crosses carved into the walls of the Chapel of St. Helena, which is located within the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, he saw a male tourist take a key and attempt to carve his name into the wall. "Immediately, all the monks and the priests and the police jump at him," Re'em recalled.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This made Re'em think of the crosses that were already carved in the wall. He noticed how they were expertly carved with deep lines into the stone. If medieval pilgrims really had carved the crosses, "Who gave permission to the pilgrims who came in ancient times to the church to carve on the wall of the most significant structure in Christianity? This does not make sense," he remembered thinking.

Re'em soon got a chance to undertake an in-depth study of the crosses. The Armenian Orthodox Church, which is in charge of the Chapel of St. Helena, temporarily closed the chapel for renovations in 2018. "[In] a really rare moment, they gave me access to the most sacred place of the chapel … where the altar is standing," Re'em said. "Around the altar [it's] full, from the ground to the ceiling, with those symmetrical crosses."

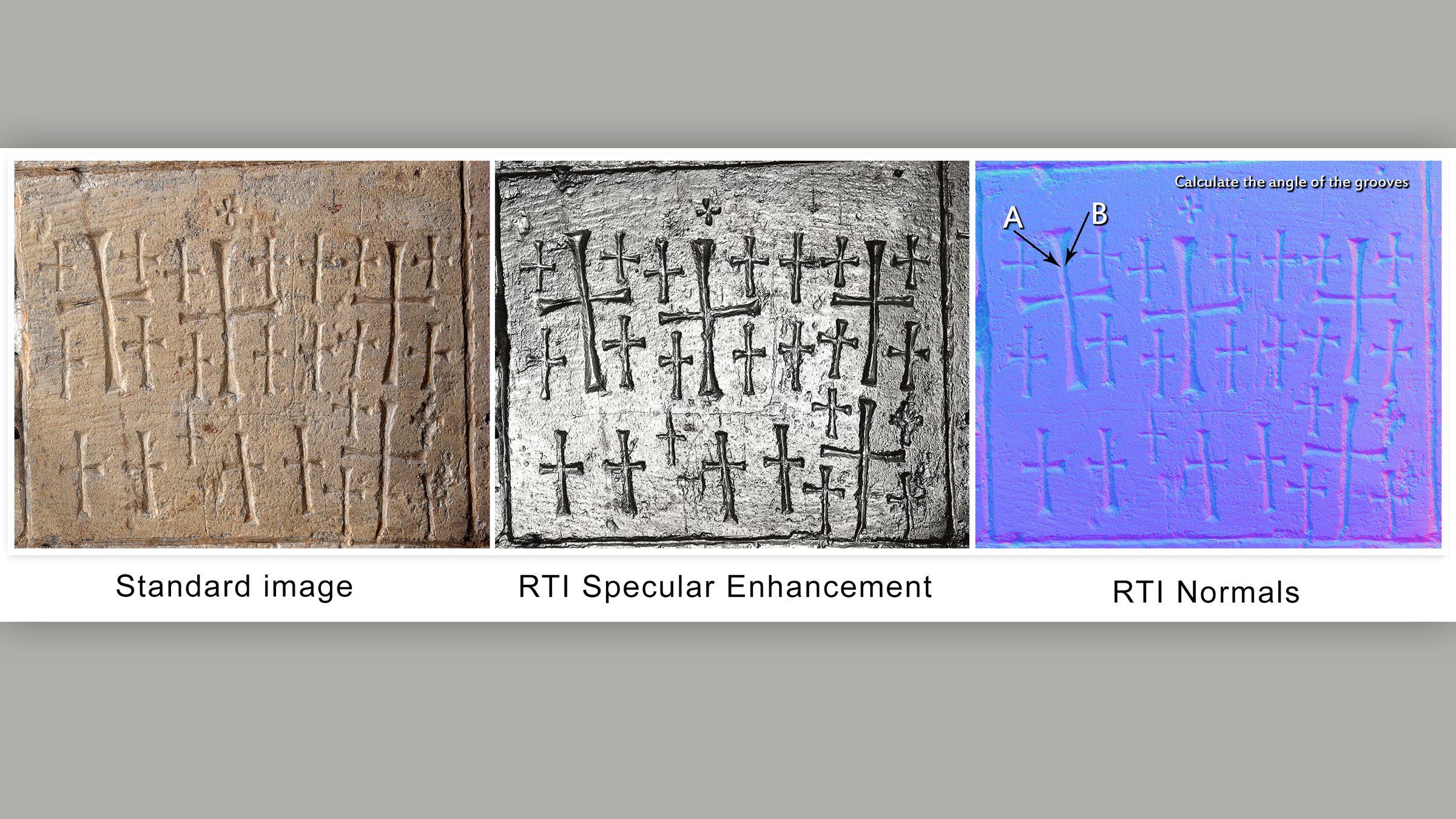

With him were project co-researchers Moshe Caine and Doron Altaratz, a professor and senior lecturer, respectively, in the Photographic Communications Department at Hadassah Academic College in Jerusalem. The team used three photographic techniques to capture the crosses' likenesses: photogrammetry, reflectance transformation imaging (RTI) and gigapixel photography.

For the photogrammetry, the team took between 50 and 500 photos per object, with each photo at a different angle, then used software that created a digital 3D image based on triangulation of all the images. Here are a few bricks and pillars they've recreated so far.

With the RTI, the team placed a camera on a tripod and then moved a light source around, taking between 48 and 72 photos per object, with the light source in a different location for each photo. These images were uploaded to software that "then runs an algorithm, which calculates a [nearly] infinite number of ways in which the surface will respond to the light," Caine told Live Science. "In other words, based on those 48 to 72 photos, you can move a virtual light source on your computer and light it from any calculable angle."

Related: Photos: Biblical-era fortress discovered in Israel

Meanwhile, with gigapixel photography, which is akin to zooming in from a worldwide to a close-up street view on Google Maps, the team took as many photos of the carved surfaces as possible, which helped them build a photo mosaic of the walls.

All of these techniques help Re'em investigate the similarities and differences, including the chiselling technique, of each carved cross. Moreover, when the researchers were photographing the crosses, they noticed inscriptions of names and dates carved alongside them. "We saw that the crosses were carved around the inscriptions, meaning that the crosses were from the same time or a little bit later from the inscriptions," Re'em said. One inscription, he noted, dates to the 1500s or 1600s — much later than the Crusades.

However, the project is ongoing. "It's not the end of the story," he said. "It could be that some of the crosses are much earlier indeed, from the time of the Crusaders, and that others are much later."

After reading about the ongoing research in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz this spring, William Purkis, a reader in medieval history at University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, reached out to Re'em. Purkis remembered visiting the Chapel of St. Helena in 2014, and noticing not just the impressive depth at which the crosses were carved into the wall but also their consistency. The common lore about these crosses being made by multiple pilgrims from Crusader times "didn't immediately strike me as the most satisfactory explanation," Purkis told Live Science. So, in that sense, "I'm in harmony with the Israel researchers' thoughts on it and findings" that the crosses were made by just a few experts, he said.

However, Purkis also had his two cents to add. He's well aware of the insatiable drive that many Western Europeans had for relics from the Holy Land in medieval times.

"We have stories from accounts of pilgrims going into the tomb itself, into the Holy Sepulchre, and snatching away chunks of rocks to take with them as souvenirs on their journey, but also as holy souvenirs, because these are places that are believed to be charged with holy power because of the direct contact with Christ's body."

It's possible that pilgrims paid a stone mason or artist to carve a cross for them in the church, and then saved the dust as a sacred keepsake, Purkis said. In medieval times, Pilgrims were known to carry small lead flasks that they filled with Holy Land souvenirs, such as water from the Jordan River. Two of these medieval flasks are in museums — the Cleveland Museum of Art and the British Museum, but it remains to be seen whether their sealed contents can be examined. However, it's still not clear whether the crosses actually date to the Crusades, so more study is needed to test the idea of medieval pilgrims taking the dust with them, Purkis said.

In the meantime, Re'em plans to continue his analysis. "In order to be more concrete in our conclusions, the name of the game is statistics," he said. "We need to check every cross, those thousands of crosses that we documented, and collect all of the data and analyze it."

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus