The most extraordinary archaeological findings of 2023

2023 was an outstanding year for finding ancient hoards, creating reconstructions and discovering burial.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The past is hiding beneath our feet and in our genes. And each new discovery from yesteryear (or yester-millennia) — be it tools, crafted treasures or DNA within our buried remains — reveals just how advanced humans were throughout the ages and how far they traded and traveled.

Kentucky man finds over 700 Civil War-era coins

The year 2023 was a breakout year for archaeological discoveries. It's no surprise that our most read story in this channel was a bright and shiny finding: that of a Kentucky man who unearthed a bumper crop of Civil War-era coins in his cornfield, all of which have already been sold at auction. It's intriguing to read about a gold hoard, but I think that these stories also give us a smidgen of hope that we, too, can find buried treasure.

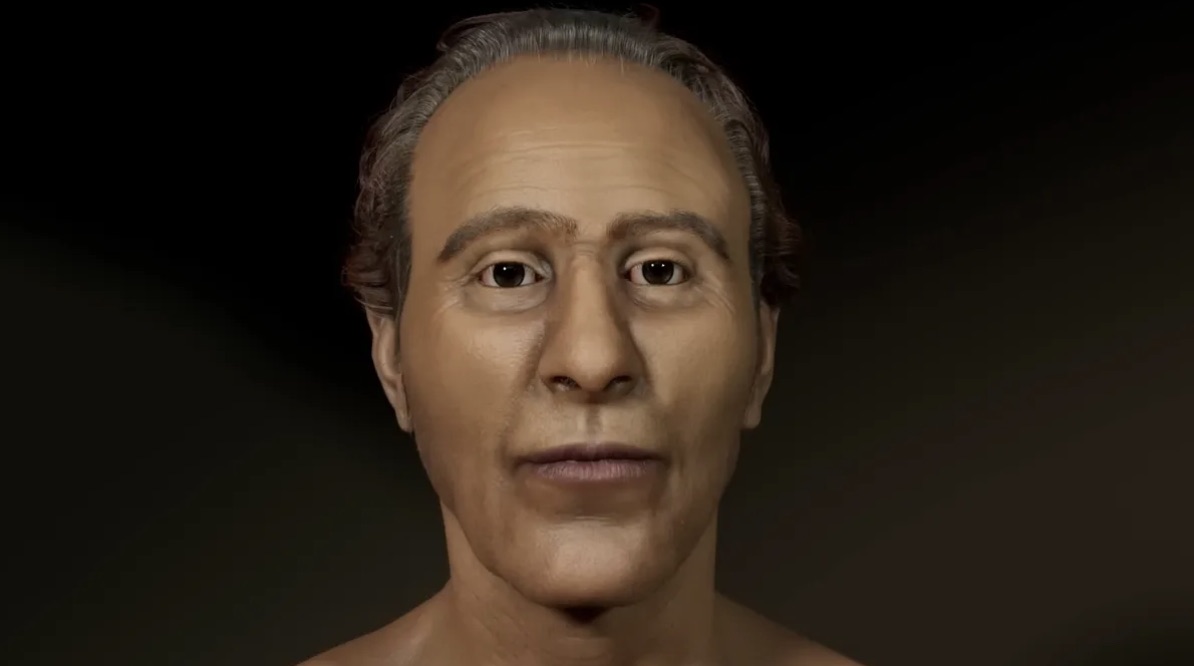

How accurate are facial reconstructions?

Facial reconstructions also took readers by storm. One of the most striking was a reconstruction of a Bronze Age woman whose remains were found in a crouching position in a 4,200-year-old grave in Scotland. Reconstructions can help bring the past alive, and in this case the forensic artist Oscar Nilsson sculpted the woman's face so that she appeared to be looking at museum-goers, rather than off into the distance.

But how accurate are these reconstructions? Our recent investigation pointed out that they're only as good as the data they're based on, which can include everything from skeletal, clothing and DNA remains to educated guesses. These reconstructions also have a subjective element, especially if they're given a facial expression or are based on incomplete information. Due to their partial or even total inaccuracy, I know that some scientists wish the reconstruction field would go away. But I appreciate these pictures of the past as long as the caveats are made clear — for instance that this Bronze Age woman's DNA couldn't be recovered, so the artist had to guess her ethnic heritage, including her skin, eye and hair color.

Burial of possible Alexander the Great courtesan unearthed

Other 2023 findings that resonated with readers include the burial of a Greek courtesan who may have accompanied Alexander the Great's army. I completely get the appeal of Alexander the Great; I took a semester-long class on the Macedonian king at university. Everything about Alexander was riveting, from his rise to power and conquering streak, to the paranoia that led him to kill his allies, and even his eventual sickness and death. We're still learning about Alexander and his contemporaries, as is evidenced by this courtesan who was buried with a bronze mirror 2,300 years ago on the road to Jerusalem.

Other popular archaeological discoveries this year included:

- A still-gleaming "octagonal" sword from the Bronze Age of Germany

- The largest-ever genetic family tree reconstructed for Neolithic people in France, which was based on ancient DNA

- The Zapotec "entrance to underworld," which archaeologists discovered under a Catholic church in Mexico thanks to cutting-edge ground-scanning technology

I can't wait to see what 2024 brings as we continue to delve into our recent and ancient past.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus