Mass child sacrifices in 15th-century Mexico were a desperate attempt to appease rain god and end devastating drought

The sacrifice of at least 42 children in Tenochtitlán, now Mexico City, was an effort to calm the anger of the Aztec rain god during a devastating drought, researchers have revealed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A mass ritual sacrifice of young children to a rain god in 15th-century Mexico coincided with a deadly drought in the region, according to new research.

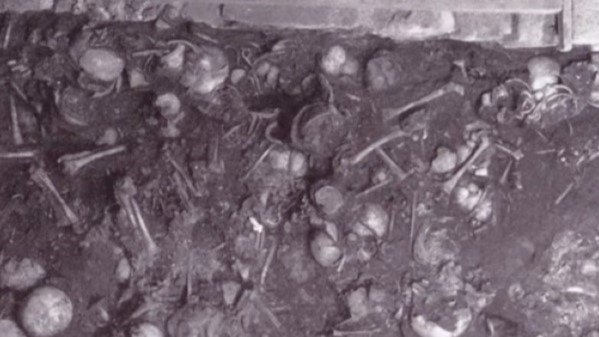

The skeletal remains of at least 42 children, ages 2 to 7, were discovered at Templo Mayor, the most significant temple complex in Tenochtitlán, now Mexico City, in 1980 and 1981.

The skeletons, which were facing up and had their limbs contracted, were placed inside ashlar boxes on a layer of sand. Some were adorned with finery such as necklaces and had green stone beads in their mouths.

Now, new research has revealed that the sacrifices were likely an attempt to end a great drought in the region by making offerings to the rain god Tláloc. The research was presented last week at the ninth Liberation through knowledge meeting: "Water and Life" at Mexico's National College.

"At first, the Mexica state tried to mitigate its effects by opening the royal granaries to redistribute food among the neediest classes, while carrying out mass sacrifices of children in the Templo Mayor to calm the fury of the tlaloque [rain dwarves who were assistants of Tláloc],” Leonardo López Luján, an archaeologist and director of the National Institute of Anthropology and History's (INAH) Templo Mayor Project, said at the meeting. "For a time, it faced the tragedy this way, but the excessive duration of the crisis made the state vulnerable, forcing it to allow the mass exodus of its people."

To find out why the mass offering was performed, INAH researchers studied geological data alongside entries in the Mexican Drought Atlas, which showed that a major drought occurred across central Mexico between 1452 and 1454.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The drought, which took place during the reign of Moctezuma I and the construction of the Templo Mayor, decimated harvests, devastated populations in the region and forced starving families to sell children to nearby towns in exchange for food, according to López Luján.

"Everything seems to indicate that droughts in early summer would have affected the germination, growth and flowering of plants prior to the canícula [dog days of summer], while autumn frosts would have attacked corn before it had ripened,” López Luján said. "Thus, the concurrence of both phenomena would have destroyed the harvests and led to occurrences of prolonged famine."

In an effort to alleviate the crisis, the sacrificed children's bodies were sprinkled with blue pigment, seashells and small birds and were surrounded by 11 sculptures made of volcanic rock.

The sculptures were made to resemble the face of Tláloc, the Aztec god of rain, water and fertility. In fact, the adornment of the children was likely an attempt to make the children resemble rain dwarves, López Luján said.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus