Lost Maya city discovered deep in the jungles of Mexico

Archaeologists discovered a lost Maya city hidden in the jungles of Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula.

Archaeologists in Mexico have discovered the remains of a lost Maya city hidden deep within the jungles of the Yucatán Peninsula.

The site, located in the Balamkú ecological reserve in the Mexican state of Campeche, contains multiple large pyramids that were built during the Classic period of the Maya civilization (between A.D. 250 and 1000). The archaeologists named the location Ocomtún, meaning "stone column" in Yucatec Maya, in a nod to the many columns dotting the site, which covers approximately 124 acres (50 hectares), according to a translated statement.

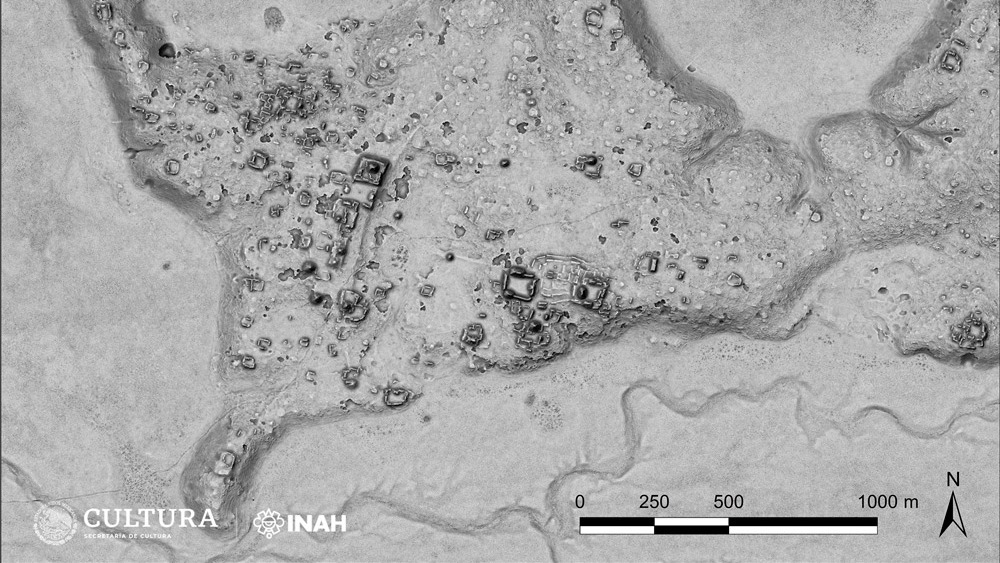

The team found the city while mapping the Maya lowlands with billions of lasers shot from an aircraft flying overhead. This technique, known as light detection and ranging, or lidar, is a noninvasive way for researchers to understand the topography of human-made structures hidden beneath foliage. In this case, the lidar revealed a Maya city with several pyramidal structures, with the tallest towering nearly 50 feet (15 meters), according to the statement.

"The site served as an important center at the regional level," lead archaeologist Ivan Ṡprajc, a department head at the Institute of Anthropological and Spatial Studies in Slovenia, said in the statement.

Related: Lasers reveal massive, 650-square-mile Maya site hidden beneath Guatemalan rainforest

The Maya had numerous city sites scattered across southern Mexico and Central America; the civilization reached its peak during the first millennium A.D. until it "collapsed" between 800 and 1000. (Although their culture has transformed, there are still Maya alive today.)

In addition to finding the pyramids and columns, while on foot, the archaeologists discovered ceramics, three plazas, a court used to play ballgames and a complex comprising "low and elongated structures arranged almost in concentric circles," according to the statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, the archaeologists are still investigating how the Maya used some of the structures.

"It is possible that they are markets or spaces destined for community rituals," Ṡprajc said. "The most common ceramic types that we collected on the surface and in some test pits are from the Late Classic (600-800 AD). However, the analysis of samples of this material will offer us more reliable data on the sequences of occupation."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus