Ancient artists high on hallucinogens may have carved dancer rock art in Peru

The research notes similarities between the carvings in southern Peru and the ayahuasca-induced art of the Amazon's Tucano people.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Ancient rock carvings in southern Peru are similar to drawings made by people high on drugs, a new study suggests.

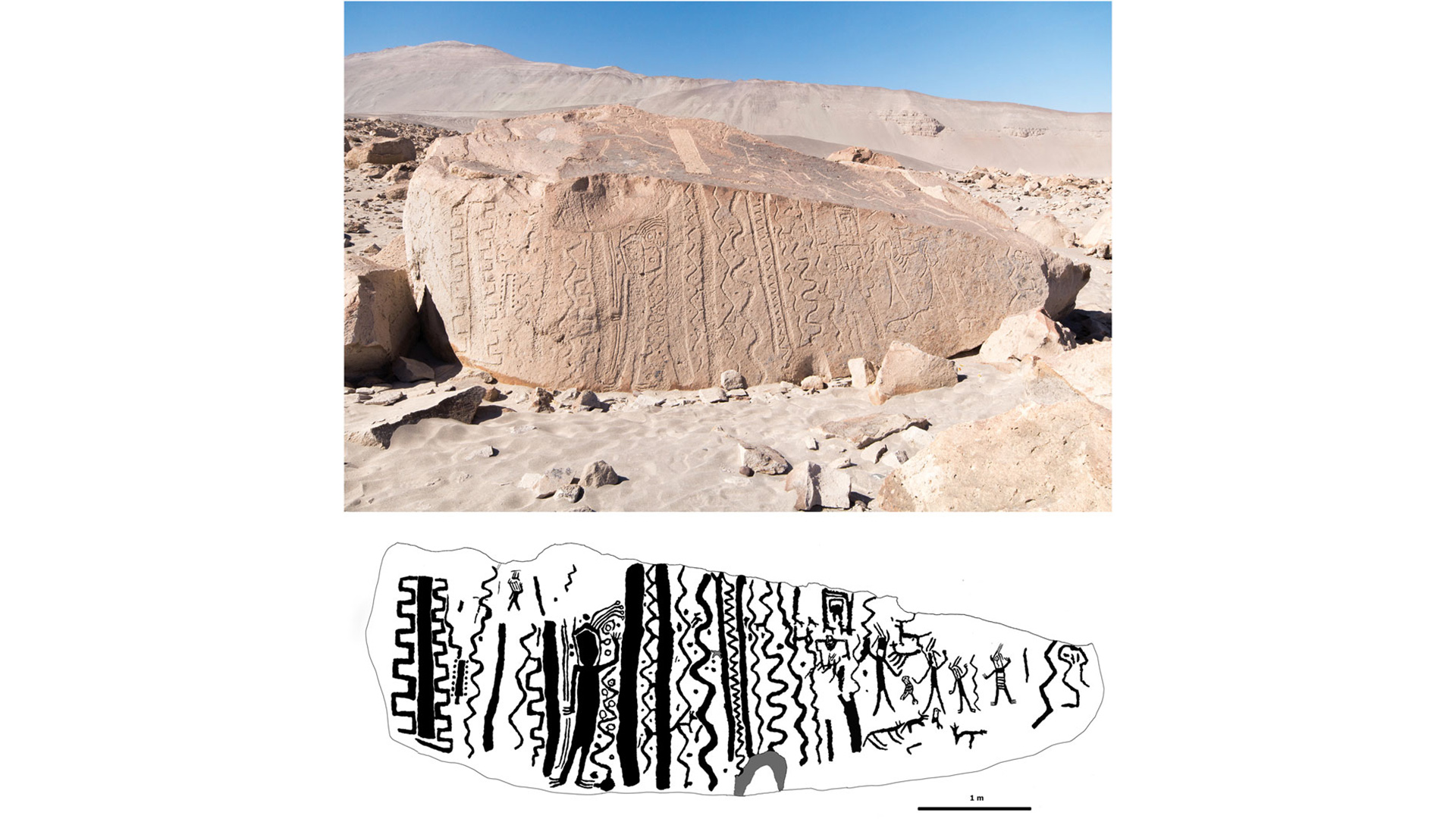

The carvings likely portray dancers and are featured on more than 2,000 boulders in the dry gorge of Toro Muerto (Spanish for "Dead Bull") in the valley of the Majes River. They are thought to be between 1,400 and 2,100 years old. Archaeologists think many were carved between 100 B.C. and A.D. 600 by the Siguas people, who were influenced by the Nasca (or Nazca) culture of southern Peru that made the famous geoglyphs in the desert of the same name.

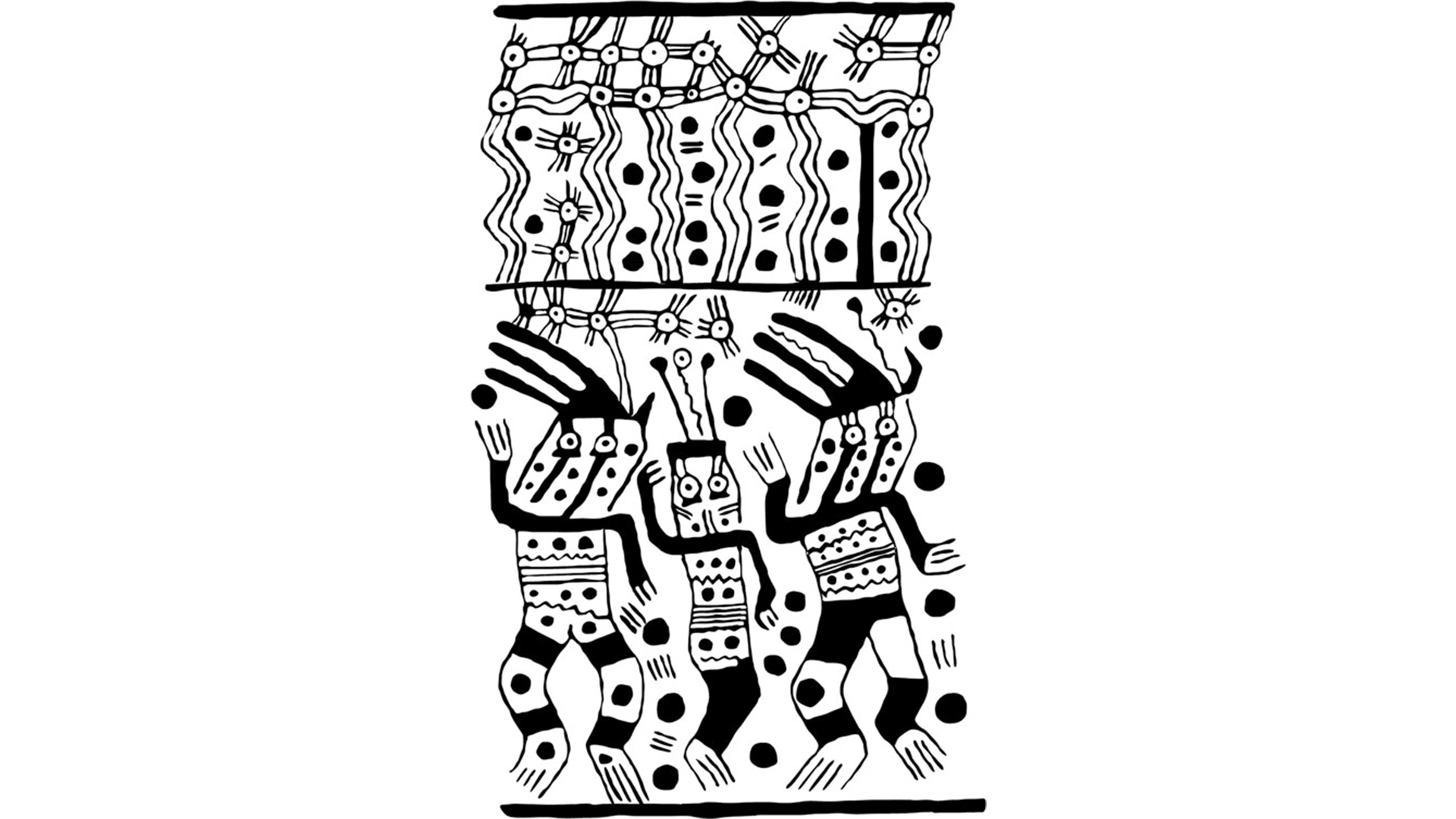

But wavy lines in the rock carvings are also strikingly similar to art made in the 1970s by the Tucano (also spelled Tukano) people indigenous to the Amazon rainforest in Colombia, Brazil and Ecuador. In those cases, the Tucano made their art during visionary states caused by ingesting the hallucinogen ayahuasca — a drink made from the vine Banisteriopsis caapi. These similarities suggest that the Peruvian rock carvings may also have been influenced by similar visions, according to the new study, published on April 3 in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal.

Related: 9,000-year-old rock art discovered among dinosaur footprints in Brazil

Dancing carvings

Study co-author Andrzej Rozwadowski, an archaeologist at Poland’s Adam Mickiewicz University, explained that many early researchers used the Latin American term "danzantes," meaning "dancers," to describe the carvings at Toro Muerto. It wasn't absolutely established that the figures were dancing, but many of them appeared to be, he told Live Science.

Many of the carvings "are characterized by dynamic poses, the knees of some of them are bent, the legs of others are straight but spread widely, suggesting movement," said Rozwadowski, who conducted the study with Janusz Wołoszyn, an archaeologist at the University of Warsaw. The research was carried out by a Polish-Peruvian team led by Wołoszyn and Liz Gonzales Ruiz, the director of the Toro Muerto Archaeological Project.

The study also suggests that geometric patterns of wavy lines and circles depicted in bands along the dancing figures may represent a parallel world, the cosmos, or an afterlife, as seen in Tucano art made in the 1970s. In a notable case, one of the carvings at Toro Muerto is remarkably similar to a set of 20th-century Tucano drawings that portray scenes from ayahuasca visions.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The logical conjecture … is that the central danzante surrounded by wavy lines is actually 'surrounded' by songs, which — embodying energy and power simultaneously — were the source of transfer to another world," the authors wrote.

Visionary drugs

Rozwadowski stressed that the similarities between the ancient Toro Muerto carvings and the ayahuasca-influenced Tucano art didn't necessarily mean that the Toro Muerto carvers, too, were high on hallucinogens; instead, the imagery could have derived from an artistic convention for portraying a parallel world or the cosmos.

In any case, the ancient peoples of southern Peru probably didn't use ayahuasca — a drink made from vines from the Amazonian rainforest, many hundreds of miles away and on the far side of the Andes.

But it's thought the Wari people, who lived in the region between A.D. 400 and 1000, used hallucinogens from the seed pods of the Anadenanthera colubrina tree, which probably existed in the region when the carvings at Toro Muerto were made.

Rozwadowski added that the large number of carvings at Toro Muerto meant it was a significant site and perhaps a place for teaching.

"One of the reasons for the importance of the site may have been the transfer of knowledge, and some petroglyphs could be a visualization of this knowledge," he said.

Justin Jennings, senior curator of Archaeology of the Americas at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto who wasn't involved in the study, said that the parallels between the Toro Muerto carvings and Tucano art were striking and may both relate to ideas of how the cosmos began.

"It's a cool idea, and very much worthy of further exploration," he told Live Science in an email.

But "Twentieth century Columbia is a world away, both geographically and temporally, and I am more hesitant than the authors in suggesting that we can think of a shared cosmovision between the Amazon and the Andes that could have endured for so long."

Editor's note: Updated at 12:05 pm EDT on April 19 to note that the co-author's name is Janusz Wołoszyn, not Wołoszyn Janusz as was previously stated.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus