Humpback whales caught on film for 1st time treating themselves to a full body scrub on the seafloor

New footage shows, for the first time, how humpbacks scrub off dead skin and parasites to stay streamlined and keep their skin healthy.

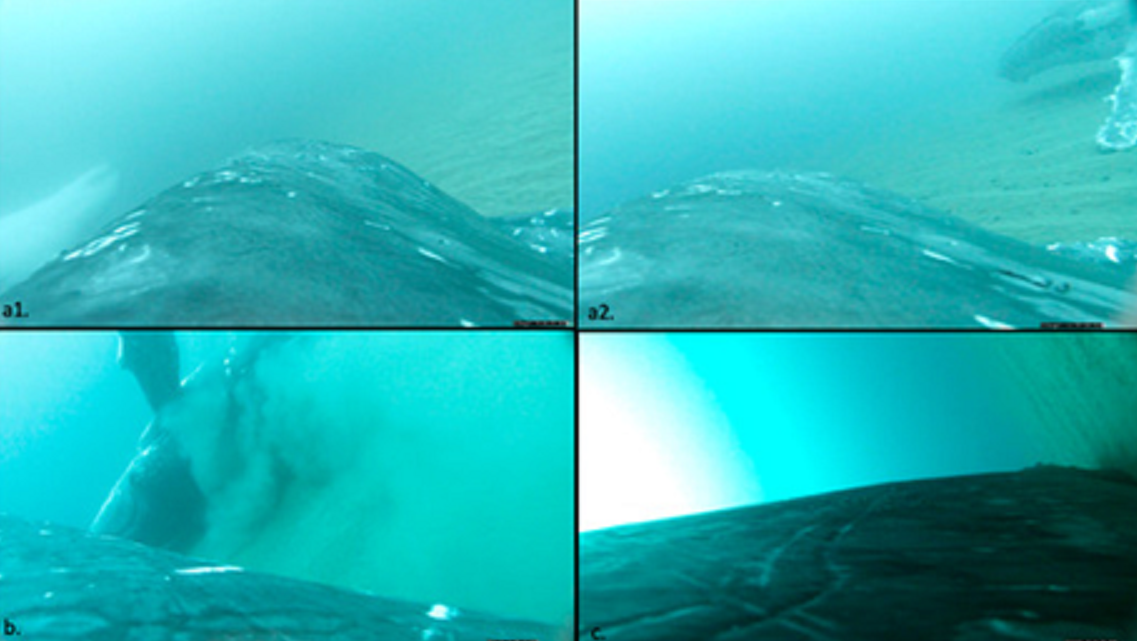

Humpback whales have — for the first time ever — been filmed rolling to and fro on sandy seabeds to scrub off dead skin and unwanted hitchhikers.

Footage captured by researchers in the Gold Coast Bay in southeast Queensland, Australia, shows the gigantic marine mammals performing full and side "sand rolls" up to 164 feet (50 meters) below the ocean's surface to shed parasites that live on their skin, known as ectoparasites, which can make the whales less hydrodynamic.

"We believe that the whales exfoliate using the sand to assist with molting and removal of ectoparasites, such as barnacles, and specifically select areas suitable for this behavior," Olaf Meynecke, a marine ecologist at Griffith University in Australia who led the research, said in a statement.

Although humpback whales have been spotted hovering and feeding near the seafloor before, this is the first time researchers have recorded them rolling in the sand. A 2016 study published in the journal Marine Biodiversity Records suggested that humpbacks used the seabed for hygienic purposes, but the reported sightings were opportunistic and made from a boat rather than underwater.

Related: Whale sighting in Australia hints at 'extremely unusual' interspecies adoption

Barnacles are sturdy little crustaceans related to lobsters and shrimp. They cement themselves to other sea creatures with one of the most powerful known natural glues, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Ocean Service. Whales need to remove these crusty parasites to stay streamlined and preserve energy, according to a study describing the sand rolling behavior, published March 12 in the Journal of Marine Science and Engineering.

The whales picked a shallow, sandy location near their migration route to exfoliate, moving head first through the substrate while they rolled. The density of parasites is generally higher around the face than elsewhere, so getting rid of them requires a rigorous rub, according to the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers tagged three humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) between August 2021 and October 2022 using suction-cup sensors that recorded high-definition video, as well as light, pressure, temperature and GPS data. The animals were on their summer migration path from tropical breeding grounds near the Great Barrier Reef, to cooler feeding grounds in Antarctica.

While they cannot exclude the possibility that the whales were trying to scratch off the tags, the researchers note that other individuals that were not tagged were also seen rolling across the seabed in the new footage. The tagged humpbacks also did not seem to be targeting the skin carrying the sensors.

The whale exfoliation also provided a tasty snack for small fish called silver trevally (Pseudocaranx georgianus), which were seen feeding on dead skin flakes just after the sand rolls.

As well as staying streamlined, exfoliating on the seabed could help humpbacks maintain healthy skin.

"Humpback whales host diverse communities of skin bacteria that can pose a threat for open wounds if bacteria grow in large numbers," Meynecke said. "Removing excess skin is likely a necessity to maintain a healthy bacterial skin community." Humpbacks remove some barnacles and skin via breaches — where a whale leaps from the water — but not all, he said.

Rolling around could also be a social activity related to play or relaxation. "During the different deployments, the sand rolling was observed in the context of socializing," Meynecke said. "The behavior was either following courtship, competition or other forms of socializing." Other whale species, including bowhead whales (Balaena mysticetus) and belugas (Delphinapterus leucas) are known to rub against rocks, pebbles and mud on the seafloor to shed excess skin.

Sascha is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She holds a bachelor’s degree in biology from the University of Southampton in England and a master’s degree in science communication from Imperial College London. Her work has appeared in The Guardian and the health website Zoe. Besides writing, she enjoys playing tennis, bread-making and browsing second-hand shops for hidden gems.