7,000 humpback whales died in the North Pacific over 10 years — and 'the blob' is to blame

New research using artificial intelligence reveals that a decline in the North Pacific population of humpback whales between 2012 and 2021 coincided with the strongest marine heat wave recorded globally.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Around 7,000 humpback whales in the North Pacific Ocean may have starved to death following the disastrous effects of a marine heat wave, a new study reveals.

From 20 years' worth of data, researchers found that a 20% drop in the North Pacific humpback whale population coincided with a marine heat wave dubbed "the blob" — an event that was responsible for record-breaking mass mortalities of multiple seabird species around the world.

In the 20th century, global populations of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) were under threat from commercial whaling. An estimated 31,865 humpback whales were killed during the years between 1900 to 1976, dropping the population of humpback whales in the North Pacific to an estimated 1,200 to 1,600 individuals at the end of commercial catches in 1976.

In the new study, published Feb. 28 in the journal Royal Society Open Science, scientists used automated image recognition artificial intelligence (AI) created by Happywhale, a database with thousands of photographs of humpback whale tails sourced from researchers and the public to find out if populations have rebounded.

The AI identified 30,484 individual humpback whales over 132,684 encounters from the photographs of their tail flukes.

Related: Kelping is a 'global phenomenon' sweeping the world of humpback whales, scientists say

This data allowed the team to work out population changes from the past 20 years. It revealed a positive recovery between 2002 to 2012, with the population growing at an average rate of 5.9% per year.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, further analysis revealed a massive decline from 2012 to 2021 as numbers dropped from around 33,488 individuals to 26,662.

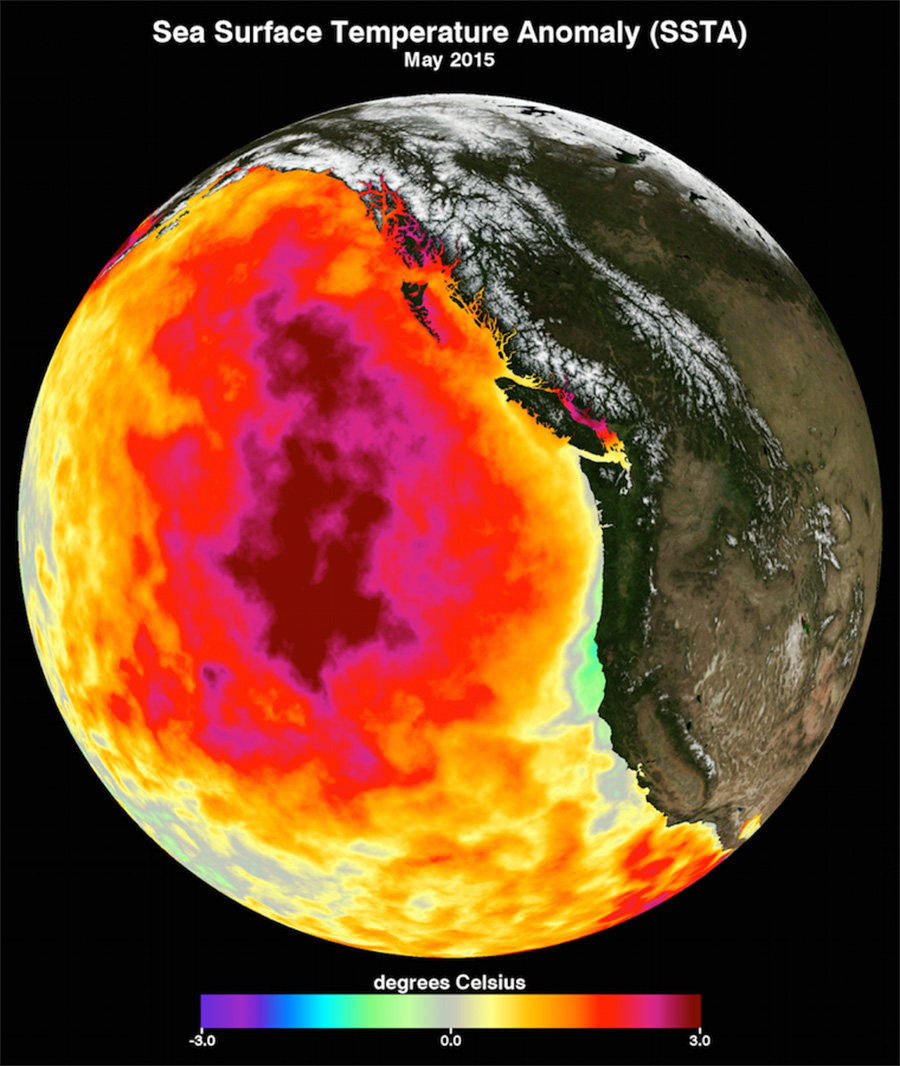

This drop coincided with the emergence of "the blob" — a patch of water in the Pacific Ocean linked to changes in the climate. In 2013, when the blob was first detected, ocean temperatures were 4 to 10 degrees Fahrenheit (2.2 to 5.6 degrees Celsius) above average. According to Science, it grew to cover an area of ocean spanning 1.5 million square miles (4 million square kilometers), stretching from the Gulf of Alaska to Mexico.

The heatwave persisted for 3 years, causing toxic algal blooms, distribution changes of fish species, countless crashes in commercial fishing and mortalities of marine life. The Northeast Pacific returned to cooler conditions at the end of 2016.

"Warmer waters are less productive, like a farm with less nutrients available to grow crops," Ted Cheeseman, co-founder and director of Happywhale and lead author of the study, told Live Science in an email.

Marine heat waves kill off organisms at the bottom of the food chain, causing a domino effect that lowers the abundance of food for small animals and then larger ones."Whales expecting to be able to get fat … on krill, anchovies, herring and other bait fish were instead suffering from starvation," Cheeseman said.

Concerns for the stability of humpback whale populations continue to grow as climate change increases ocean temperatures. "Today's extreme may become the normal state in 20 years," Cheeseman said. "If that happens, the heatwave of the future may mean genuinely unlivable oceans."

Elise studied marine biology at the University of Portsmouth in the U.K. She has worked as a freelance journalist focusing on the aquatic realm.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus