Mouse Gets Human Liver

A mouse has been given an almost completely human liver so that it is susceptible to human liver infections, including Hepatitis B and C, and responds to human drugs, opening a door to new study methods and treatments for debilitating human liver diseases, researchers say.

Many infectious diseases are host-specific, meaning they are well adapted to infecting certain organisms, but not others. For example, only humans and chimpanzees can catch Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C. This specificity helps to prevent widespread infection across species, but it makes it hard to study human diseases in other animals.

The usual way around this problem is to grow and treat human cells in a dish, but this isn't possible with liver cells, called hepatocytes. "Human hepatocytes are almost impossible to work with as they don't grow and are hard to maintain in culture," explains study-author Inder Verma, a professor in the Laboratory of Genetics at the Salk Institute in La Jolla, Calif.

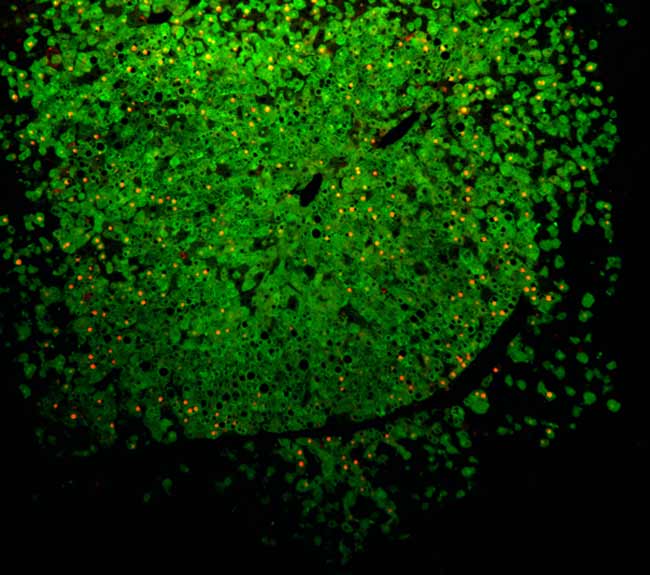

Mice whose own hepatocytes have been replaced with human liver cells, a "chimeric mouse," provide a solution to all these hurdles.

Verma and his colleagues had previously generated a mouse with a partially "humanized" liver, but wanted to improve their method to achieve almost complete transformation. They use a special mouse that has liver problems of its own, but whose problems can be kept in check with a drug called NBTC. Taking away NBTC allows transplanted human hepatocytes to take hold and populate the mouse liver with human cells. With the new system, nearly 95 percent of the liver cells are of human origin.

Importantly, unlike normal mice, these chimeric mice could develop Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C. And when given the standard drugs for treating these diseases, the "humanized" liver inside the mouse responds just like a normal human liver.

"This robust model system opens the door to utilize human hepatocytes for purposes that were previously impossible. This chimeric mouse can be used for drug testing and gene therapy purposes, and in the future, may also be used to study liver cancers," Verma said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The model may also be sued to test therapies for other diseases that involve the liver, including malaria, said Karl-Dimiter Bissig, a post-doctoral researcher at the Salk Insititue.

The results were published online today the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

- Top 10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species

- Lab Freak: Mighty Mouse Just Runs and Runs

- The 10 Most Outrageous Military Experiments

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus