How a Man-Made Tornado Could Power the Future

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Editor's Note: Each Wednesday LiveScience examines the viability of emerging energy technologies — the power of the future.

Coiled up in a tornado is as much energy as an entire power plant. So a Canadian engineer has a plan to spin up his own twister and extract energy from its tethered tail.

It all depends on heating the air near the surface so that it is much warmer than the air above.

"You can generate energy whenever you have a temperature gradient," said Louis Michaud. "The source of the energy here is the natural movement of warm and cold air currents."

These so-called convective air currents are only useful if they can be channeled in some way. That is why Michaud proposes using a tornado as a kind of drinking straw between the warm ground below and the cold sky above. Wind turbines placed at the bottom could generate electricity from the sucked-up air.

Whirlwind tour

Tornadoes and hurricanes form when sun-heated air near the surface rises and displaces cooler air above. As outside air rushes in to replace the rising air, the whole mass begins to rotate.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Michaud got the notion of a man-made tornado — what he calls the Atmospheric Vortex Engine (AVE) — while working as an engineer on gas turbines.

"When I looked further into it, I didn't run into anything that was impossible," Michaud told LiveScience.

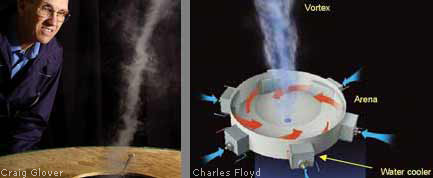

The AVE structure is a 200-meter-wide arena with 100-meter-high walls. Warm humid air enters at the sides, directed to flow in a circular fashion. As the air whirls around at speeds up to 200 mph, a vacuum forms in the center, which holds the vortex together as it extends several miles into the sky.

The concept is similar to a solar chimney with the swirling walls of the vortex replacing the brick walls of the tower. But the AVE can reach much higher into the sky where the air is colder.

With wind turbines at the inlets to the arena, Michaud calculates that as much as 200 megawatts of electricity (enough for a small city) could be extracted without draining the vortex of its power.

"Look at natural tornadoes that destroy a house or carry off a car and still have plenty of energy left over," he said.

Waste heat

Michaud imagines the AVE could get its warm air from the exhaust of a power plant.

"Most power plants reject more than half of the heat that they make," he said.

The AVE could generate energy from this waste heat because it connects the ground to the upper atmosphere where the temperature gets as low as negative 60 degrees Celsius (80 degrees below zero Fahrenheit). This cold reservoir draws the warm air up fast enough to turn turbines.

"All you have to do is send the heat up there," Michaud said, and the extra energy from the AVE could increase the output of a power plant by 40 percent.

Making the tornado dependent on a waste heat supply would also be a built-in safety feature. "If it came off the base, there would be nothing to sustain the vortex," Michaud said.

He said the vortex might produce a little extra precipitation in the surrounding area.

To build a 200 megawatt AVE facility would cost $60 million, Michaud estimates. This implies a cost per megawatt that is lower than all existing power generation technologies.

Michaud has tested many small prototypes and is currently working on a 4-meter wide AVE near his home in Ontario. The research comes mostly out his own pocket book, as he has not found an investor yet.

"Utility companies are risk-adverse," he said. "They prefer to buy from established vendors."

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus