Maya Civilization Was Ultraviolent, Even Before Its Collapse

A hieroglyphic inscription found in an ancient Maya city now reveals kingdoms making up this civilization waged extraordinarily destructive warfare much earlier than previously thought, a new study finds.

These findings may shed light on what may or may not have brought about the end of the Maya empire, researchers said.

The ancient Maya civilization encompassed an area twice the size of Germany, occupying what is now southern Mexico and northern Central America. At the height of the Maya empire, known as the Classic period, which stretched from about A.D. 250 to at least 900, perhaps as many as 25 million people lived in the region, potentially rivaling the population density of medieval Europe. [7 Bizarre Ancient Cultures That History Forgot]

Mysteriously, this ancient Maya Golden Age collapsed more than a thousand years ago. Its population declined catastrophically to a fraction of its former size. The ruins of its great cities are now mostly overgrown by jungle.

Scientists have suggested a number of potential causes of the end of the Classic period, none of which are mutually exclusive. Droughts may have led to critical water shortages. Deforestation linked with farming could have led to loss of fertile topsoil via erosion.

An escalation of violence may have also played a role in the Maya downfall. Previous research suggested that during the Classic period, warfare among the ancient Maya was mostly ritualized and limited in scope, with strict rules of engagement centered on procuring elite captives for tribute and ransom and minimal involvement of noncombatants. However, archaeologists unearthed signs that the ancient Maya at the end of the Classic period practiced the extraordinarily destructive tactics of total warfare, where both civilian and military resources were targeted, at times resulting in the widespread destruction of cities. [7 Technologies That Transformed Warfare]

"In termination events, cities were completely destroyed and royal families were removed — sometimes thrown in wells or buried in ceremonial centers," study lead author David Wahl, a research geographer at the U.S. Geological Survey in Menlo Park, California, told LiveScience.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Now, scientists find that the ancient Maya may have engaged in this type of total war much earlier than previously thought.

"We now have, for the first time, a picture of the broader impacts of a Classic-period Maya attack," Wahl said. "We see that the tactics used had negative consequences for the local population in such a way that, in this case, the trajectory of settlement in the city was permanently changed."

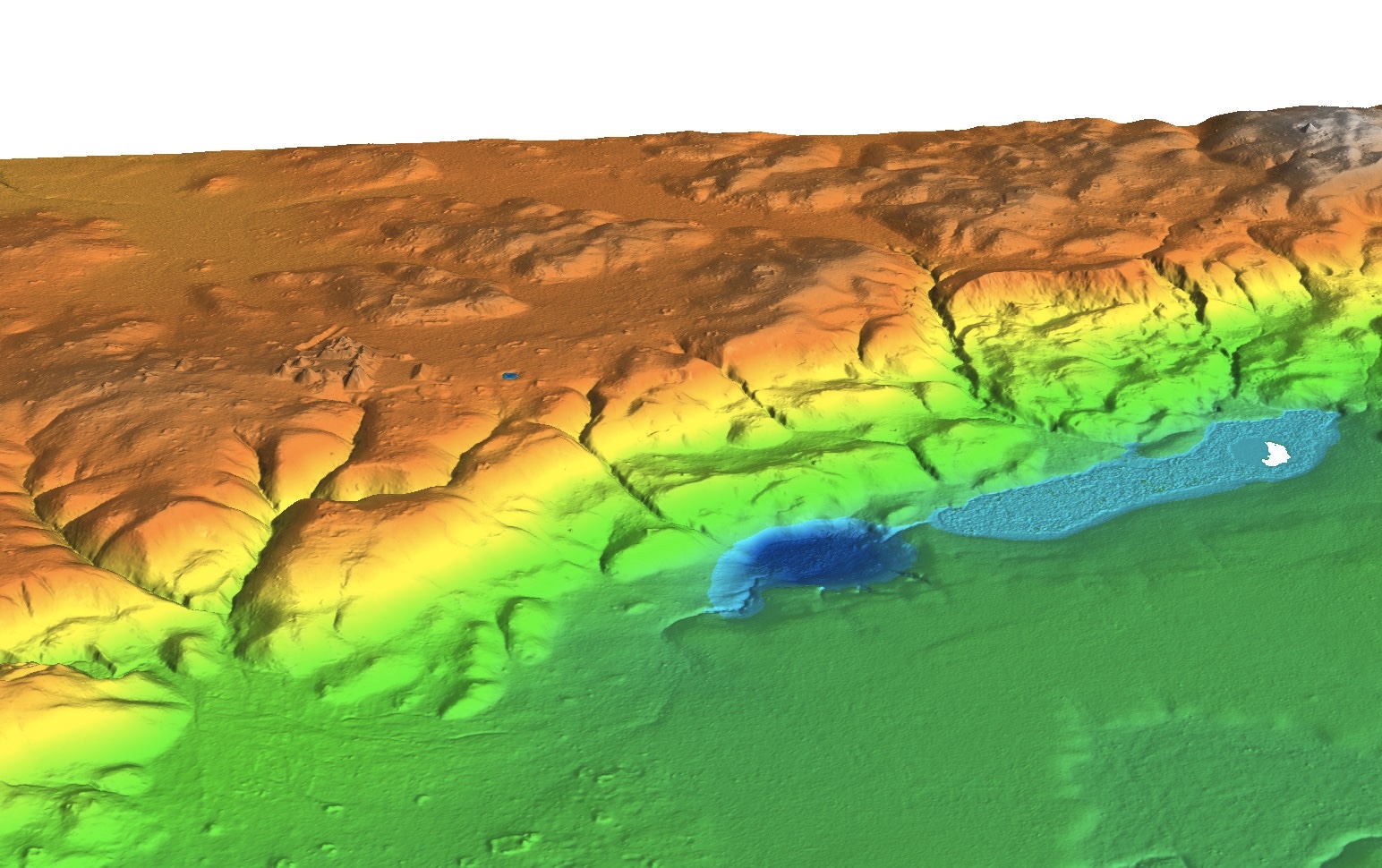

The researchers made their discovery while investigating past environmental changes around the archaeological site of Witzna in the Petén region of Guatemala, which encompasses the northern third of that country.

"The biggest challenge in this study — indeed, most of the work I've done in Petén — is the remoteness of the field site," Wahl said. "There are no roads to the lake, so all equipment and supplies are carried in, down a steep 100-meter [330 feet] escarpment. The lake is ringed by sawgrass — sedges with edges as sharp as they sound — and it took a crew of around eight people three days to penetrate the sedges and build a pier just to access the open water. This involved standing in chest-deep water swinging machetes to clear a path. Once we reached open water, we were pretty alarmed to see at least a dozen alligators lingering about intently watching our activity."

The scientists unexpectedly discovered a stela, or stone column, with readable emblem glyphs — a hieroglyphic inscription dedicated to a city's lord. This revealed the site's Mayan name, Bahlam Jol, alongside customary symbols of rule — the scepter of the lightning god K'awiil and a shield on a bound captive.

At Naranjo, a Classic Maya city 20 miles (32 kilometers) south of Witzna, prior work had found another stela. The inscription stated that in 697, Bahlam Jol was attacked and burned for a second time. In lake deposits adjacent to Witzna, Wahl and his colleagues discovered a 1.2-inch (3 centimeters) layer of charcoal resulting from a massive fire, by far the largest in the 1,700 years worth of sediment they looked at. Carbon dating of a seed in this charcoal layer suggested the fire happened in the last decade of the seventh century, supporting the Naranjo stela's inscription.

The razing of all key structures across Witzna, including the royal palace as well as monuments inscribed with glyphs, supported the idea this site experienced major destruction. In addition, Wahl and his colleagues also found that before the end of the seventh century, lake deposits showed many signs of human activity — such as farming residues and vestiges from burning — but these declined dramatically after the presumed attack.

Although the destruction seen at Witzna was reminiscent of that seen at the end of the Classic period, there were differences. "You do see the persistence of the royal lineage there after the attack, whereas in the Terminal Classic, the royal family is either killed or removed," Wahl said. "But in Witzna, the city was wiped out, like you see in the Terminal Classic."

The symbol "puluuy," which was used to describe the burning of Bahlam Jol, was previously seen at other Maya sites. This suggests that such burning was perhaps more common in ancient Maya warfare than previously known, the researchers said.

All in all, these findings suggest such destructive total warfare was practiced even during the peak of ancient Maya prosperity and artistic sophistication, challenging theories suggesting that it was unique to the waning days of Maya civilization. As such, perhaps it played less of a role in the collapse of the Maya empire than some had previously suggested.

"I think, based on this evidence, the theory that a presumed shift to total warfare was a major factor in the collapse of Classic Maya society is no longer viable. We must look for other causes," study co-author Francisco Estrada-Belli at Tulane University in New Orleans said in a statement.

The scientists detailed their findings online Aug. 5 in the journal Nature Human Behavior.

- In Photos: Hidden Maya Civilization

- 25 Cultures That Practiced Human Sacrifice

- The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth

Originally published on Live Science.