An Alien Star Was Just Caught Shooting an Enormous Plasma Blast into Space

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

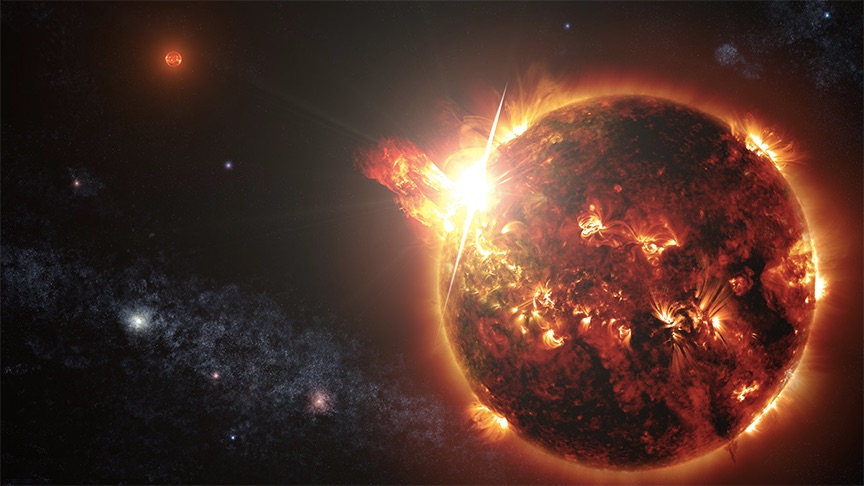

Scientists have, for the first time, spotted plasma blasting off the surface of a giant star.

The observation, published May 27 in the journal Nature Astronomy, represents the first direct look at a coronal mass ejection (CME) from a star other than our sun. And the observation revealed a plasma blast of astonishing scale: roughly 2.6 quintillion lbs. (1.8 quintillion kilograms) of superhot matter — peaking at 18 million to 45 million degrees Fahrenheit (10 million to 25 million degrees Celsius). Note: A quintillion is equal to a billion billions.

The CME was enormous in human terms, but it was difficult to spot. From Earth it looked like a comparatively slow, small and cool mass that followed a bright stellar prominence — or loop of even hotter, faster-moving, heavier plasma that doesn't fully escape the star — off the star's surface.

That CME mass is "about 10,000 times greater than the most massive CMEs launched into interplanetary space by the sun," the researchers behind the paper said in a statement. [15 Amazing Images of Stars]

And that scale is a big deal.

We know that our sun tends to do two things at the same time: emit a lot of radiation (that's called a flare) and spit out CMEs (hot bursting bubbles of plasma). And astronomers know that a stronger flare generally is accompanied by a stronger CME. But until now, there had been no direct evidence for this relationship on other, larger stars.

But HR 9024, a giant star about 450 light-years away from Earth, produced a CME that closely matched an accompanying flare and that scaled with the size of the star. This is evidence, the researchers said, that the rules governing CMEs in our solar system hold elsewhere in the universe for other types of stars.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To pull off the measurement, the researchers relied on the High-Energy Transmission Grating Spectrometer, an instrument aboard NASA's orbiting Chandra X-Ray Observatory. It's the only instrument humans have made that's capable of observing stellar events on this relatively small scale within a solar system.

In addition to providing evidence for how CMEs behave on other stars, the observation may help explain how stars' masses and rates of spin fall over time, the researchers said. When a CME's mass escapes, it takes some of the star's momentum with it. This CME was big enough that, assuming CMEs like this are common, it could explain how stars shrink and slow down.

- Space Weather: Sunspots, Solar Flares & Coronal Mass Ejections

- Totally Active: Eclipse Photos Reveal Sunspots, Solar Flares

- Six Cosmic Catastrophes That Could Wipe Out Life on Earth

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus