Faces Re-Created of Ancient Europeans, Including Neanderthal Woman and Cro-Magnon Man

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

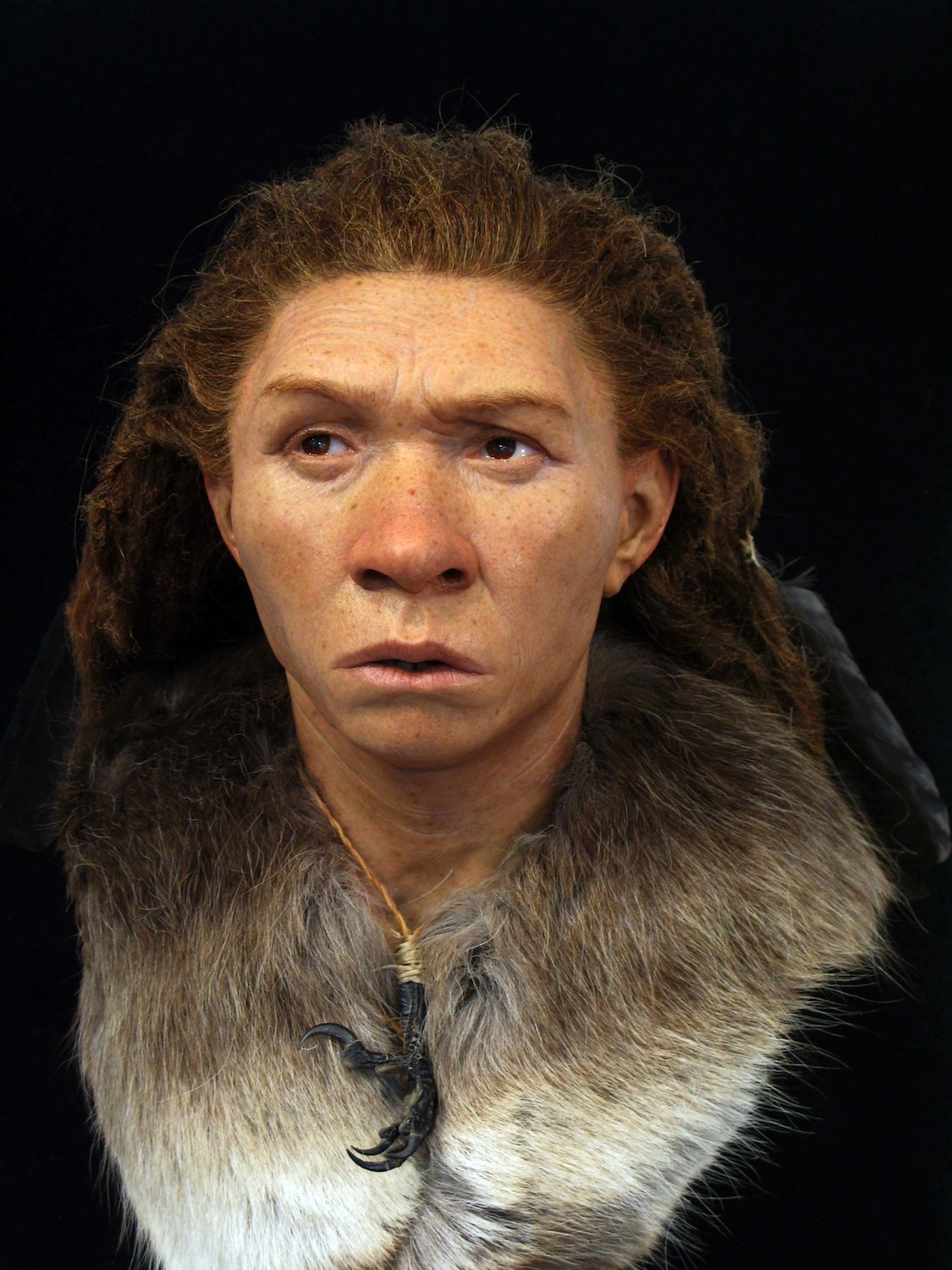

About 5,600 years ago, a 20-year-old woman was buried with a tiny baby resting on her chest, a sad clue that she likely died in childbirth during the Neolithic. This woman and six other ancient Europeans — including a Cro-Magnon man, a Neanderthal woman and a man-bun-sporting dude from 250 B.C. — are on display at a museum in Brighton, England, now that a forensic artist has re-created their faces.

These re-creations took hundreds of hours of work and are based on every available detail scientists could glean from these people's remains, including radiocarbon dating; the collection of dental plaque; and, when possible, the analysis of ancient DNA that detailed each person's eye, skin and hair color, said Richard Le Saux, senior keeper of collections at the Royal Pavilion & Museums in England, where the exhibit opened on Jan. 26.

This exhibit aims to shine a light on the past inhabitants of Brighton and mainland Europe by featuring hyper-realistic portrayals of their faces, Le Saux told Live Science in an email. [See the Amazing Reconstructed Faces]

To re-create these heads, Oscar Nilsson, a forensic artist based in Sweden, took 3D printed replicas of their skulls and got to work. After reviewing data on the individuals' heritage and ages of death, he used plasticine clay to sculpt muscles and then covered that with artificial skin, which included details such as wrinkles and pores. The first two faces — those of a Neanderthal woman from Gibraltar and a Cro-Magnon man from France — show the history of Europe's early human inhabitants. According to DNA research, "early Cro-Magnons like this one had really dark skin," Nilsson told Live Science in an email.

The woman who likely died in childbirth, known as the Whitehawk girl (named for Whitehawk, Brighton, where she was found), also had dark skin. While her remains didn't have any preserved DNA, other burials from her time period did, and those people's genetic material shows "their skin color to be at least like today's people living in North Africa, or in fact, a bit darker," Nilsson said.

Meanwhile, the best hairstyle award for the group may go to the Slonk Hill man, who lived in England around 250 B.C. This man died young by modern standards — between the ages of 24 and 31 — but "his bones tell the story of a man living a good life: being robust, strong and healthy, he also had handsome facial features," Nilsson said. "His teeth are unique — he has gaps [and] spaces between his teeth, a condition called diastema."

Nilsson gave the Slonk Hill man a "Suebian knot," a style in which the hair is tightly swept to the side of the head in a bun. "A number of Germanic tribes have variations of this hairstyle," Nilsson said, explaining his choice.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Another individual — the Romano-British "Patcham lady," who lived around A.D. 250 — may have been murdered.

"Her skeleton shows she lived a hard life," Nilsson said. "Her spine [may] have suffered from hard labor, resulting in a spinal condition called Schmorl's nodes." But what really grabbed Nilsson's attention was a nail driven into the back of the woman's head.

There were iron nails found in the grave, so "this could be the result of a somewhat sloppy sealing of the coffin she was laid in," Nilsson said. "Or, more intriguing[ly], it could be a token of superstitious beliefs. There are examples with deceased people being buried with nails in and around them, to prevent them from haunt[ing] the neighborhood after death."

"We'll never know in this case," he noted.

That may be true, but the visiting public will still wonder, as each of the faces looks at you, inviting you learn the person's story. And that's exactly what Nilsson wanted. "I use silicone, prosthetic eyes and real human hair to achieve this [effect]," he said. "But they are also reconstructions, forensically rebuilt, muscle by muscle. This is actually very close to what they looked like in life."

The exhibit is now on display at The Elaine Evans Archaeology Gallery in Brighton.

- In Images: An Ancient Long-Headed Woman Reconstructed

- Album: A New Face for Ötzi the Iceman Mummy

- Photos: The Reconstruction of Teen Who Lived 9,000 Years Ago

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus