'It Was Just Dead Brain Tissue': Seattle Woman Dies from Extremely Unusual Infection

It started with a sinus infection that wouldn't go away. So, in an attempt to give the 69-year-old Seattle woman some relief, doctors recommended that she use a neti pot regularly to rinse out her sinuses. And that's where things went wrong, according to a recent report of the woman's case.

The first sign of trouble was a quarter-size rash on the right side of her nose and some raw, red skin around the outside of her nasal passages, according to the case report, published in September in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases.

The rash didn't go away, despite several visits to a dermatologist, the report said. Then, about a year after the rash first emerged, the woman had a seizure. [27 Oddest Medical Cases]

A CT scan revealed a 1.5-centimeter (0.6 inches) lesion in her brain.

"For all intents and purposes, it looked like a tumor," said senior case report author Dr. Charles Cobbs, a neurosurgeon at the Swedish Medical Center in Seattle. This wasn't necessarily surprising, Cobbs told Live Science, as the woman had a history of breast cancer.

But when Cobbs operated to remove the mass, "it was just dead brain tissue," making it difficult to determine what it actually was. So, he just took a sample and sent it to neuropathologists at Johns Hopkins University for further analysis.

After the operation, the woman was sent home, according to the report. But then Hopkins pathologists came back with a verdict: The infection looked "amoebic," said Cobbs, who thought, "that's ridiculous," upon hearing the news. But the woman's condition was deteriorating.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

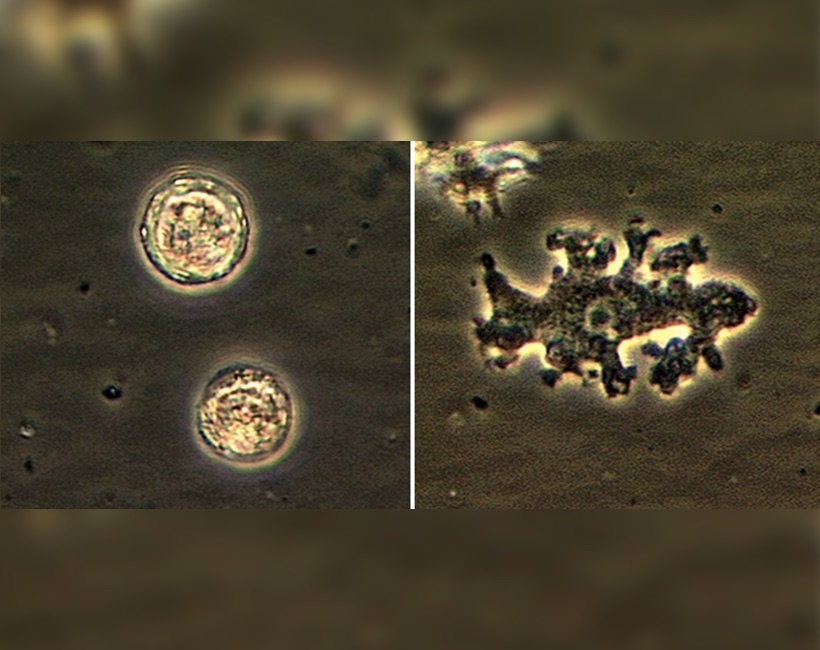

Cobbs "took her immediately back to surgery … and removed this thing that had been growing in size," he said. When the doctors looked at these samples of the tissue under the microscope, they could see the amoebas.

This time, the team contacted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), who FedExed the hospital a brand-new drug to try, Cobbs said. But unfortunately, the infection was too severe, and the woman died.

It wasn't until after the woman's death that additional lab results came back from the CDC. The woman turned out to have an infection with a "brain-eating" amoeba called Balamuthia mandrillaris. The CDC found evidence of the amoeba in both the woman's brain tissue and tissue from the rash on her nose, Cobbs said.

B. mandrillaris infections are "extremely unusual" and "almost uniformly fatal," the authors wrote in the report. The amoeba was discovered by CDC scientists in the brain of a dead mandrill baboon in 1986, and it was declared a new species of amoeba in 1993. Since then, more than 200 cases have been diagnosed worldwide, with at least 70 cases in the U.S., the CDC says.

"It's so exceedingly rare that I'd never heard of it," Cobbs said.

Cobbs said he suspects that the woman got infected by using the neti pot with unsterilized water; indeed, rinsing the sinuses with unsterilized water has been linked in the past to another deadly brain-eating amoeba infection called Naegleria fowleri. The CDC notes, however, that "little is known at this time about how a person becomes infected" with the amoeba.

Unlike N. fowleri, B. mandrillaris is much more difficult to detect, according to the report. For example, the amoeba can be mistaken for certain immune cells, which it resembles under the microscope. And it's hard to grow the amoeba in the lab, because it doesn't grow on agar, a commonly used cell-culturing medium used in labs. It can only grow on mammalian cells and other amoebas, the report said.

In addition, images from brain scans may resemble other conditions that are more common, including tumors and bacterial infections, the authors wrote.

Because B. mandrillaris infection can be so difficult to diagnose, the authors wrote, it's possible that "many more" cases of the disease have been missed.

Still, Cobbs stressed that people should not panic about the possibility of this infection, given its rarity. "People should just go about their normal lives," he said. But if you do use a neti pot, "definitely use sterile water or saline," he added.

- 5 Key Facts About Brain-Eating Amoeba

- 7 Absolutely Horrible Head Infections

- Tiny & Nasty: Images of Things That Make Us Sick

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus