Archaeologists Just Discovered the Mangled Remains of a Slaughtered Barbarian Tribe in Denmark

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Some 2,000 years ago, a ragtag troop of about 400 Germanic tribesmen marched into battle against a mysterious adversary in Denmark, and they were slaughtered to the last man.

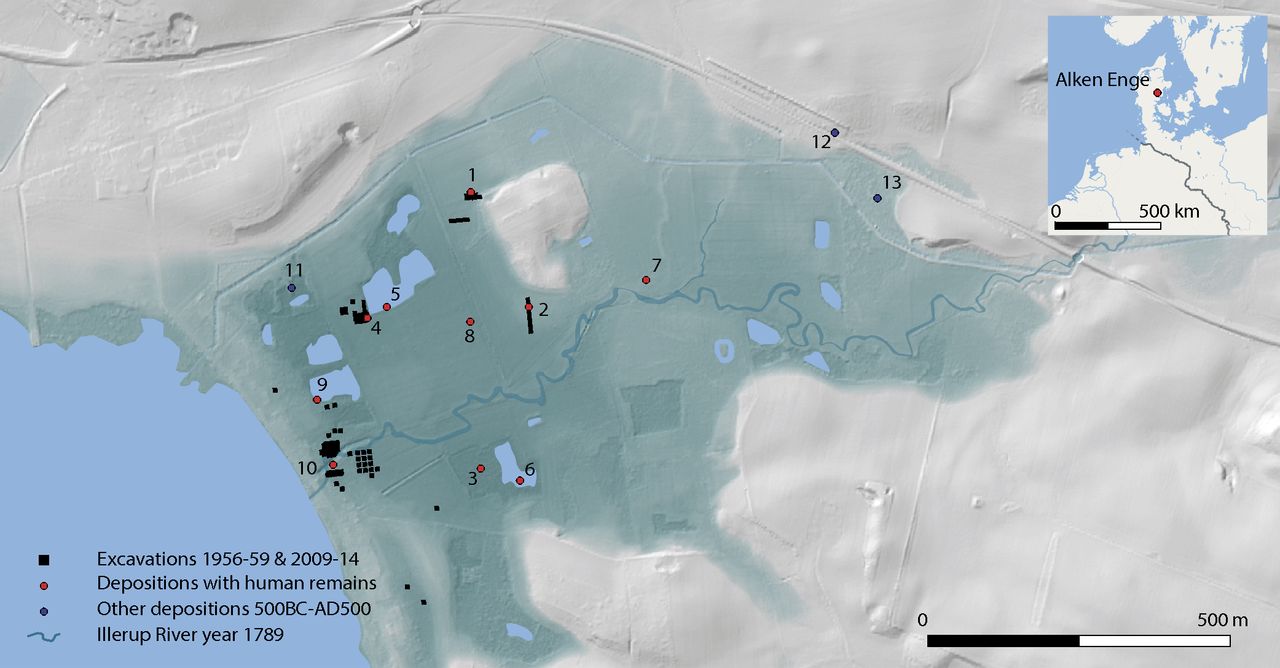

Or at least that's the story their bones tell. Exhumed from Alken Enge — a peat bog in Denmark's Illerup River Valley — between 2009 and 2014, nearly 2,100 bones belonging to the dead fighters have given archaeologists a rare window into the post-battle rituals of Europe's so-called "barbarian" tribes during the height of the Roman Empire. In a new study published online May 21 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of researchers from Aarhus University in Denmark dug into the bloody details.

"The ferocity of the Germanic tribes and peoples and their extremely violent and ritualized behavior in the aftermath of warfare became a trope in the Roman accounts of their barbaric northern neighbors," the authors wrote in the new study. Despite these historical accounts, little evidence of these practices has ever been discovered in archaeological finds — until now. [See Photos of the Mutilated Iron Age Skeletons]

"Comprehensive slaughter"

In the Alken Enge find, archaeologists unearthed 2,095 human bones and fragments from the peat and lake sediment across 185 acres of wetlands in East Jutland. These bones belonged to 82 distinct people — seemingly all men, most of them 20 to 40 years old — but likely account for just a fraction of the bones initially deposited in the area, the researchers wrote. After analyzing the geographic distribution of the bones, the team estimated a minimum of 380 skeletons were originally interred in the water.

This population "significantly exceeds the scale of any known Iron Age village community," the researchers wrote, suggesting the men were recruited from a large area to participate in a common battle.

Using radiocarbon analysis, the team dated the bones to between 2 B.C. and A.D. 54 — sometime between the reigns of the Roman emperors Augustus (27 B.C. to A.D. 14) and Claudius (A.D. 41 to 54). During this time, Rome expanded its empire north into Europe but met fierce resistance from the scattered tribes who lived in modern-day Germany and Denmark. Some tribes allied with the Empire, and infighting between tribes was common.

The bones of the men at Alken Enge are thought to be the casualties of one such tribal battle. Ancient weapons like axes, clubs and swords were found scattered about the site, and it was clear to the researchers that many of the skeletons had sustained critical battle wounds before dying.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The relative absence of healed sharp force trauma suggests that the deposited population did not have considerable previous battle experience," the researchers wrote. Indeed, the scrappy group of soldiers met "comprehensive slaughter."

Ritual burial or hasty cleanup?

Finding boneyards of dead soldiers is no rarity in archaeology; what truly excited the researchers about Alken Enge was the seemingly ritualistic way in which the skeletons were buried. [25 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries]

For starters, it appears that the skeletons were deposited in the lake after they had decomposed in the wild for anywhere between six months and a year. Nearly 400 of the bones were hatched with gnawing tooth marks probably left by scavenging animals such as foxes, wolves or dogs. Moreover, the absence of bacterial decay on the bones suggests that the men's inner organs were removed, decomposed or eaten by scavengers before their ultimate burial, the researchers wrote.

Whether it was a friend or foe who did the burying is still unclear. The men's arm and leg bones were severed from their torsos. Few intact skulls were present, but many cranial fragments appeared to have been smashed with a club or other bludgeoning tool, the researchers said. Four pelvic bones hung around a single tree branch with deliberate intent.

"Alken Enge provides unequivocal evidence that the people in Northern Germania had systematic and deliberate ways of clearing battlefields," the researchers concluded. The find certainly "points to a new form of postbattle activities" in Germanic tribes at the dawn of the current era — but what it all means is still a mystery.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus