Woman's Bones Vanish Before Doctors' Eyes

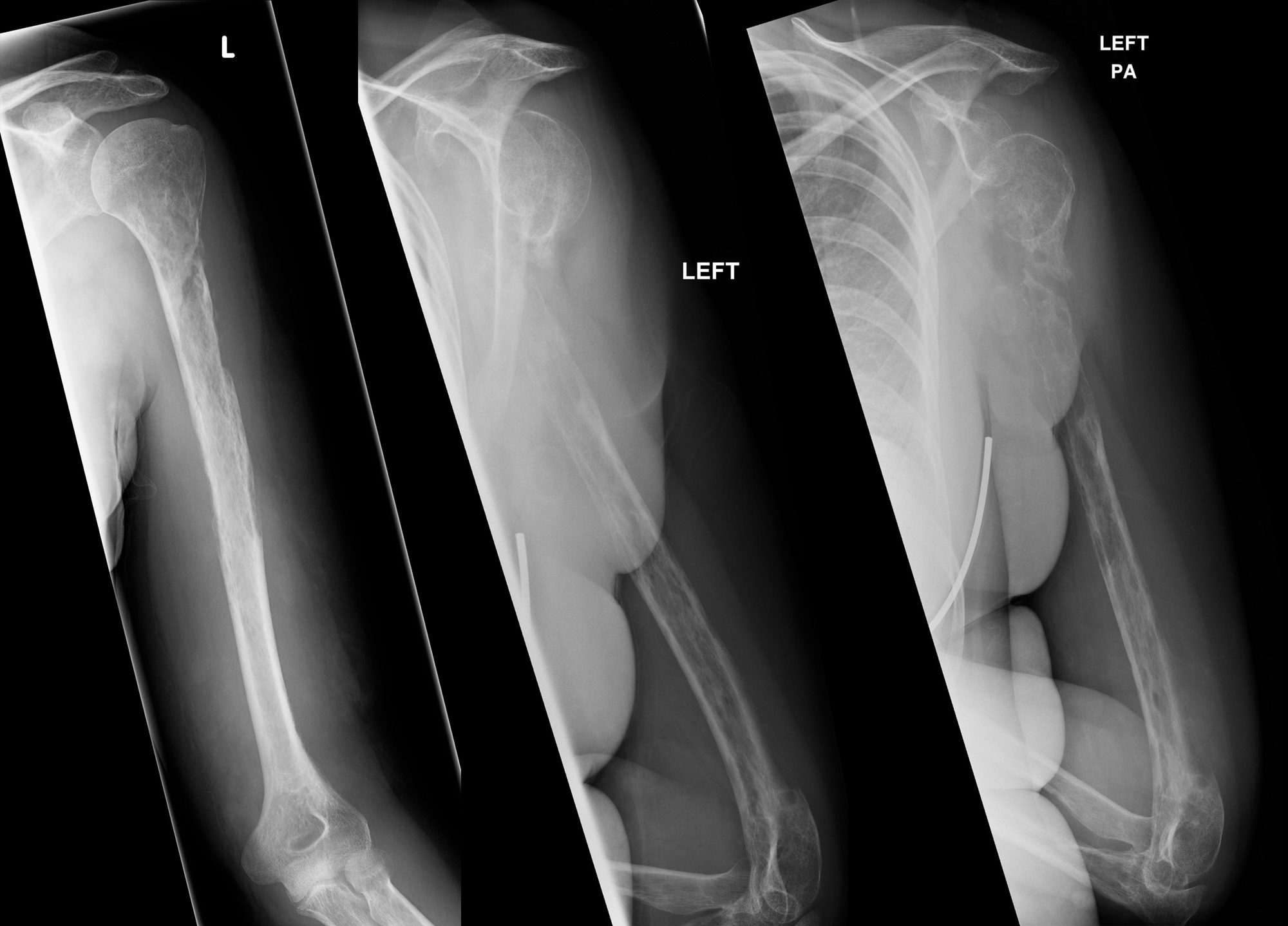

The woman's symptoms were puzzling: The pain in her arm and shoulder wouldn't go away, and doctors couldn't figure out what was causing it. Then, the case got even stranger: In a series of X-rays, her bones seemed to be disappearing before doctors' eyes.

This unusual phenomenon provided the clue needed to solve the mystery, according to a new report of the case from doctors at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh in Scotland. The woman was diagnosed with Gorham-Stout disease, also known as "vanishing bone disease," an extremely rare condition in which people experience progressive bone loss, according to the report. It was published March 22 in the journal BMJ Case Reports. Only 64 such cases have been reported in the medical literature, the researchers said. [27 Oddest Medical Cases]

Doctors don't know what causes the condition; no genetic or environmental triggers of the disease have ever been identified, according to the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD).

But doctors do know that people with this condition experience abnormal growth of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels, the channels that carry lymph (a fluid that contains infection-fighting white blood cells). These aggressively growing vessels infiltrate the bone, which causes it to break down, according to NORD. Fibrous connective tissue or benign (noncancerous) blood vessel tumors then replace the bone.

Mysterious case

The 44-year-old woman was previously healthy; she went to the doctor when she experienced increasing pain in her left shoulder. On an X-ray, doctors saw a lesion in her humerus bone (the bone in the upper arm), and they initially thought she might have cancer. But her biopsy results didn't show cancer; instead, the results were inconclusive. Several months later, another biopsy revealed a benign blood vessel tumor.

Over the next year, the woman continued to have pain and swelling in her arm, and her bone would fracture from just minor injuries. But she still hadn't received a diagnosis.

About 18 months after the woman first went to the doctor, scans revealed her "vanishing" bones; both her humerus and her ulnar bone (one of the two bones in the forearm) appeared to be disappearing on X-rays. Additional biopsies showed that blood vessel growths were replacing her bone tissue.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A challenging disease

The severity of Gorham-Stout disease varies from person to person. In most cases, the condition is a "regional" disease, meaning it stays in one area of the body, according to Boston Children's Hospital. For example, a patient, like the one in this case, may have the disease in her shoulder and arm, but not elsewhere in the body.

Other commonly affected bones include the ribs, spine, pelvis, skull, collarbone and jaw. In some cases, the condition leads to paralysis if the disease affects bones of the spine or skull base, according to NORD. In addition, if the disease affects the rib cage, patients may develop a buildup of fluid between the membranes that line the lungs — a potentially fatal complication.

There is no standard treatment for the condition, and therapies are usually aimed at a patient's specific symptoms, according to National Institute of Health's Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). Some therapies include surgery to remove the affected bone areas, radiation treatment to prevent the disease from spreading and bisphosphonates, which are drugs to prevent bone loss. In some cases, the disease improves spontaneously, without treatment, GARD says.

"Ultimately, this is a challenging disease where evidence-based management remains lacking," the researchers of the new report concluded.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.