If the Falling Chinese Space Station Hits You, Is Anyone Liable?

China's Tiangong-1 space station is expected to hit Earth sometime over Easter weekend, between March 30 and April 2, according to the European Space Agency's (ESA) Space Debris Office in Darmstadt, Germany.

Authorities aren't sure where it will hit, except somewhere under the station's orbital path— between 43 degrees north and 43 degrees south latitudes. That orbital path includes the United States and most of the world's population. On the off chance a piece of Tiangong-1 hits you, is anyone liable?

While the following shouldn't be construed as legal advice, there are some general guidelines to help you understand more about space junk and liability. [In Photos: A Look at China's Space Station That's Crashing to Earth]

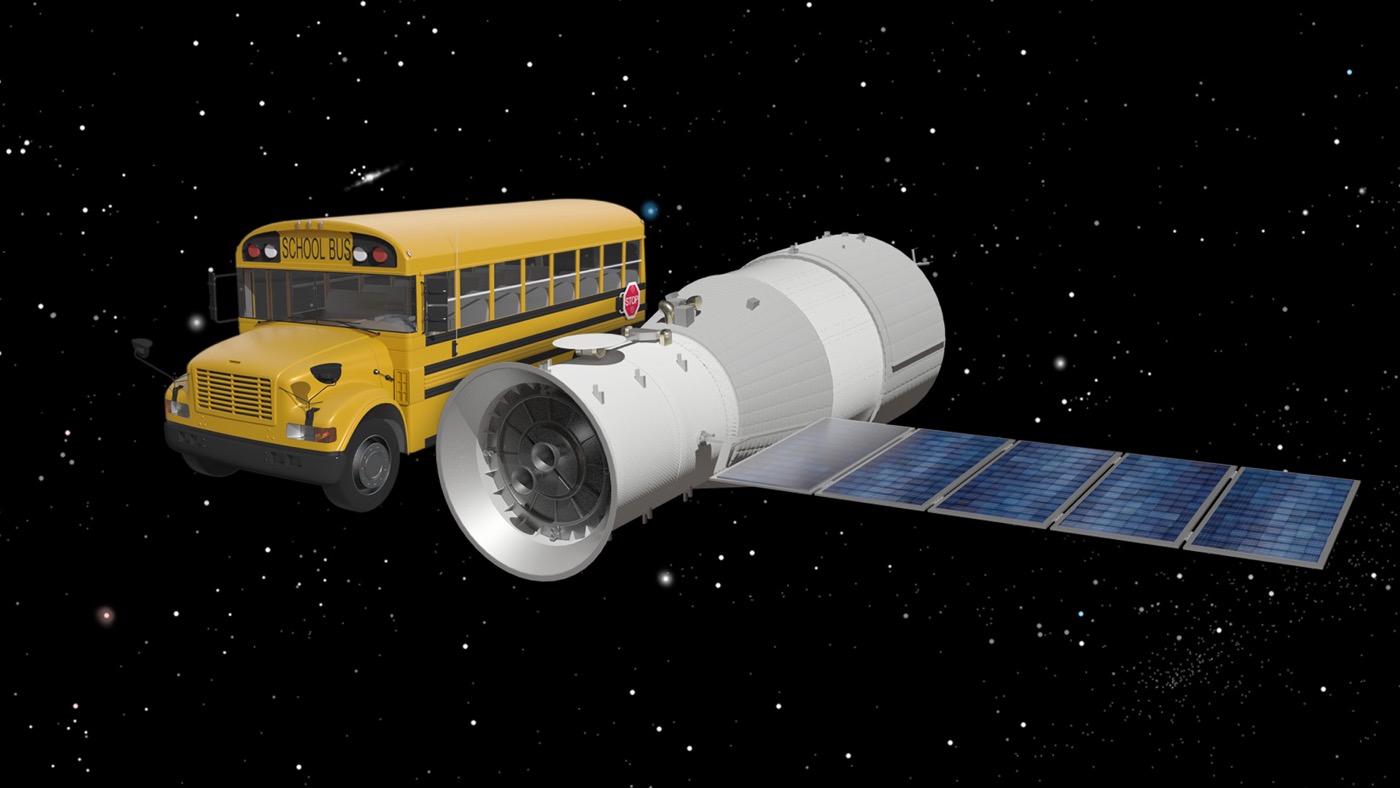

First, it is unlikely that many pieces of Tiangong-1 will fall to Earth. The station is just about 18,740 lbs. (9 tons), compared with the almost 100-ton defunct U.S. Skylab space station that broke up in Earth's atmosphere in 1979. NASA tried to aim Skylab at a remote spot in the ocean south-southeast of Cape Town, South Africa. However, the agency miscalculated the rate of Skylab's decay. Some parts of the space station slammed into Australia, east of Perth. Luckily, there were no reported injuries.

Even if parts of Tiangong-1 survive the descent, the odds that space junk will hit you are a million times less than they would be for winning the Powerball jackpot, or about 1 in 292 million, Live Science previously reported. Even your odds of getting struck by lightning are greater — about 1 in 1.4 million. By contrast, the top cause of death in the United States in 2014 was cardiovascular disease, with 193 deaths per 100,000 people.

The liability for space debris rests with the United Nations Convention on International Liability for Damage Caused By Space Objects, which came into force in 1972. Under the terms of the convention, damage includes "loss of life, personal injury or other impairment of health; or loss or of damage to property of States or of persons ... or property of international intergovernmental organizations." Claims typically must be launched through diplomatic channels within one year of the incident. Compensation is meted out under international law and "the principles of justice and equity," the convention states.

The nation (or nations) that launched the object is "absolutely liable" for compensating the injured party, according to the convention. Damages, however, do not apply to nationals of the launching state, or foreign nations "participating in the operation of that space object from the time of its launching or at any stage thereafter until its descent" — including if the launching nation invites the foreign nationals to attend the launch or recovery operations. [What Should You Do If You Find a Piece of China's Crashed Space Station?]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Just one person, Lottie Williams of Tulsa, Oklahoma, has ever been hit by space junk, according to news reports — but she wasn't hurt. On Jan. 22, 1997, Williams saw "a flash of light resembling a meteor," according to Wired. A few moments later, something metallic fell onto her shoulder. NASA reportedly said her incident came close to the timing of the re-entry and breakup of the second stage of a Delta rocket coming into Earth's atmosphere. Most of the rocket's debris landed in Texas, a few hundred miles away.

There is at least one precedent for damages paid out under the Liability Convention of 1972, Brian Weeden, a technical adviser with the Secure World Foundation, said in a 2013 interview with Live Science sister site Space.com. In 1978, a Soviet nuclear-powered satellite called Cosmos 954 crashed into northwestern Canada, releasing large amounts of radioactive material.

Canada asked for 6 million Canadian dollars in compensation, which works out to C$21.6 million ($16.7 million) in 2018 dollars. The case never made it to court, but the Soviet Union eventually paid Canada half of the requested amount — C$3 million ($2.3 million) — following diplomatic negotiations.

Weeden spoke to Space.com shortly after Chinese space debris apparently destroyed a defunct Russian weather satellite in January 2013. The debris arose from a 2007 anti-satellite missile test that China had launched against its own defunct weather satellite, called FY-1C.

"There's never been a court case on this topic, and there's no standard for what 'fault' or 'negligence' is in regard to collisions in space," Weeden told Space.com at the time, adding that he is not a lawyer.

"I know lawyers who could probably argue that China is at fault because they deliberately destroyed the FY-1C in an ASAT test, but plenty of other lawyers who could argue that since there have been six years of natural forces acting on the orbit of the piece of Chinese debris, it was actually caused by force majeure … All of that means it's extremely unlikely anything definitive will come of this from some sort of lawsuit," he added.

Originally published on Live Science.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.