SpaceX Falcon Heavy: What's Up with the Giant Rocket?

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

UPDATE: At 3:45 p.m. EST, SpaceX's Falcon Heavy rocket successfully launched from launchpad 39A in Cape Canaveral, Florida.

A humongous rocket is about to launch into space today (Feb. 6), if all goes as planned, according to SpaceX.

The window for launching is now scheduled to open at 3:05 p.m. EST, when the Falcon Heavy's Merlin engines will ignite on Launch Pad 39A at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida. That's the same launchpad that hosted the Apollo moon missions and NASA's space shuttles, according to Live Science sister site Space.com.

In theory, the 230-foot-tall (70 meters) rocket could carry 140,700 lbs. (63,800 kilograms) into low Earth orbit, making it the world's most powerful rocket around today. (For this test launch, however, the rocket will carry a Tesla Roadster past the orbit of Mars.) That's twice as much baggage as its closest competitor, United Launch Alliance's Delta IV Heavy, can carry. And apparently, it's cheap, so a ride into low Earth orbit — between about 100 and 1,200 miles (160 to 2,000 kilometers) above Earth's surface — would cost about $90 million, according to SpaceX. And — if successful — it's not a one-way trip for the rocket, which is reusable. [In Photos: SpaceX's 1st Falcon Heavy Rocket at the Pad]

Cheap and reusable. How did Elon Musk's SpaceX pull off this creation? For starters, the company did a bit of recycling.

The Falcon Heavy is basically a merger of three Falcon 9 rockets, Space.com reported. Two Falcon 9 first-stage boosters are attached to a core booster (in between the two side boosters), which is a modified first-stage booster from the Falcon 9. These three cores, which are connected at the base and the top of the center core's liquid oxygen tank, make up the rocket's first stage, at the bottom of the rocket.

To counteract gravity's downward tug, the three cores are composed of 27 Merlin engines, which have 5.13 million lbs. of thrust (23 newtons), according to SpaceX. The more thrust force, the higher the velocity and the farther an object can travel before gravity wins the race. And to sling an object like the Falcon Heavy into an orbit around Earth, the booster needs to achieve a velocity of at least 18,000 mph (29,000 km/h), according to Aerospace Corp.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Here's how other rockets stand up to the Falcon Heavy in terms of thrust:

- Delta IV Heavy: 2 million pounds of force (8.7 million newtons).

- NASA's Saturn V (which carried the Apollo missions): 7.5 million pounds of force (33 million newtons).

- NASA's space shuttles: 6.25 million pounds of force (28 million newtons).

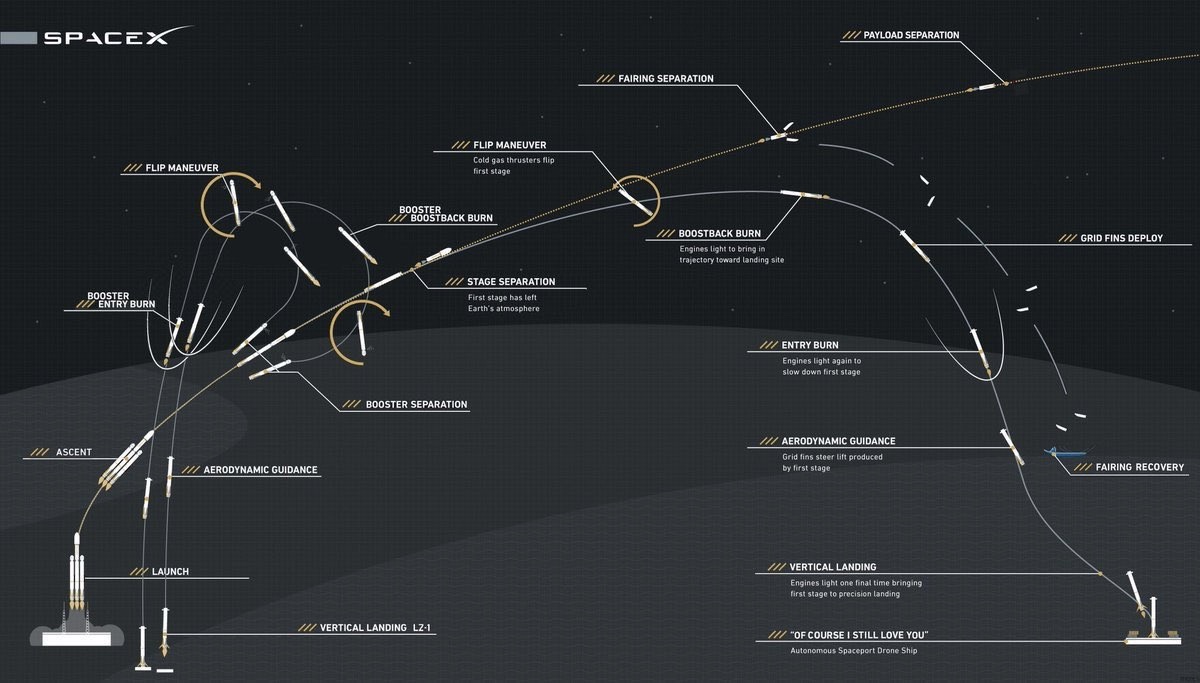

At liftoff, the booster trio will be at full thrust (i.e., firing on all cylinders), before the center core will throttle down, SpaceX explained. Then, after the side boosters separate from the rocket, the center core will throttle back up.

The second stage, which holds a Merlin engine that burns liquid oxygen and kerosene and sits right below the payload-carrying pointy top of the Falcon Heavy, is what delivers the payload to orbit after the main engines shut down and the first-stage cores have separated, according to SpaceX.

As for what happens to those boosters? All three sport fins and landing legs that they'll use for landing attempts. The two side cores will attempt to land at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, Space.com reported. The core booster will try to land on a drone strip in the Atlantic Ocean called "Of Course I Still Love You."

Originally published on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus