Trash-Blasting Lasers Could Help Clean Up Space Junk, China Says

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Far above your head right now, whizzing across the majestic canvas of space at 17,500 mph (28,200 km/h), is a load of garbage.

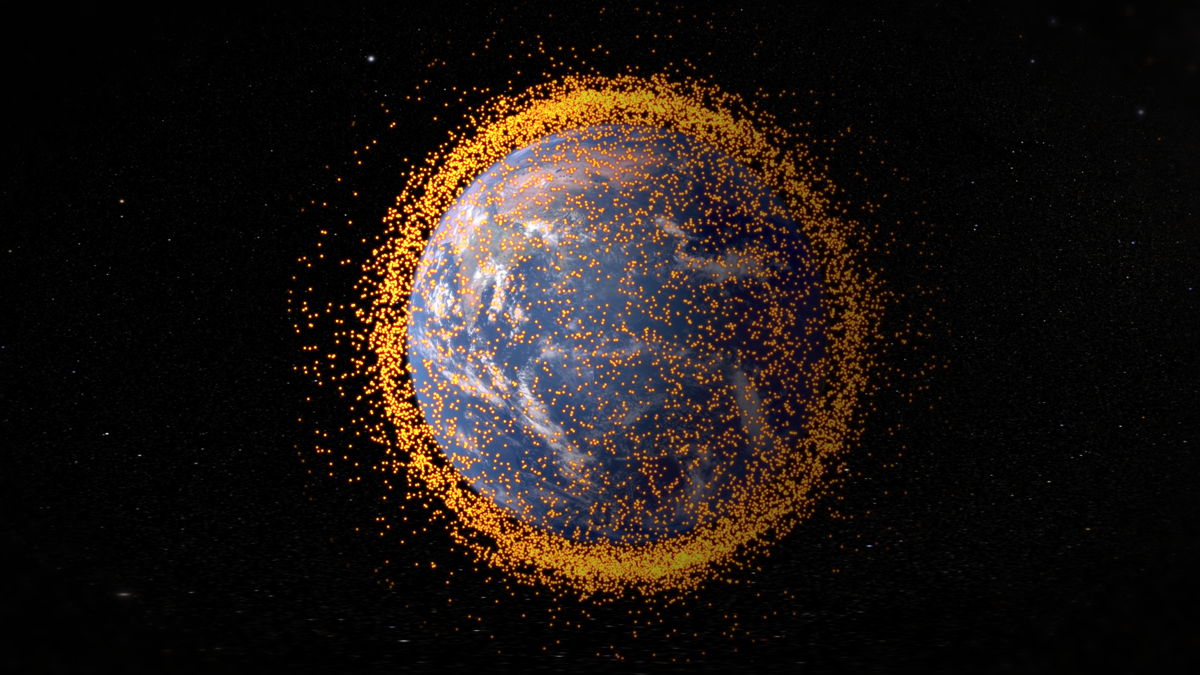

More than 500,000 pieces of human-made debris — colloquially known as "space junk" — orbit the Earth at any given time, NASA reported in 2013. At least 20,000 items in this extraterrestrial scrap heap are larger than a softball, and can include such massive detritus as entire defunct satellites and abandoned launch vehicles.

Such huge obstacles naturally pose a danger to new space missions, according to NASA. But just as dangerous are the many millions of pieces of debris that are so small they can't even be tracked. "Even tiny paint flecks can damage a spacecraft when traveling at these velocities," NASA officials wrote. "In fact, a number of space shuttle windows have been replaced because of damage caused by material that was analyzed and shown to be paint flecks." [10 Futuristic Technologies 'Star Trek' Fans Would Love to See]

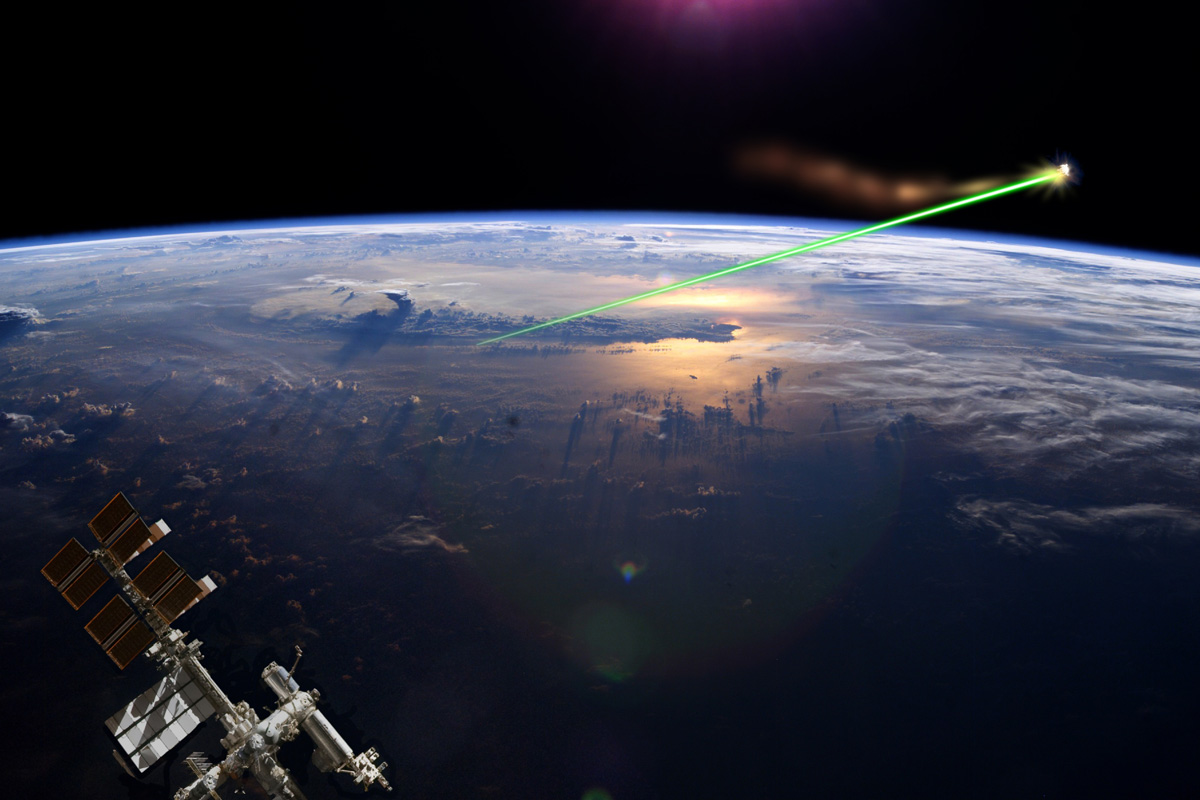

As more space missions (and more space junk) enter orbit every year, the need to clean up Earth's outer atmosphere grows ever more pressing, scientists say. Researchers previously proposed using magnets, ultrathin nets and giant harpoons to tackle the trash problem. How to clean up the smallest debris — the millions of particles that are less than 10 cm wide — is a trickier question to answer. Now, in a new paper published in the February 2018 issue of Optik - International Journal for Light and Electron Optics, researchers at the Air Force Engineering University in China propose a solution: just blast the junk with satellite-mounted lasers.

The study researchers ran multiple numerical simulations to model how the orbital path of space debris could be affected by radiation from space-based lasers. Essentially, the idea is to lower the orbital path of the debris enough so that it re-enters Earth's atmosphere, below about 120 miles (200 kilometers) above the surface, where it would burn up.

The models showed that orbital measurements called inclination, which describes the angle between the plane of orbit and Earth's equator, and right ascension of ascending node (RAAN), which describes the angle between Aries and the satellite as it crosses Earth's equator while passing from the Southern to Northern Hemisphere, proved crucial to the calculations. According to the models, small-scale debris cleanup proved most effective when the RAAN of the space-based laser stations matched the RAAN of the debris.

While these resultsmake a strong theoretical case for using space-based lasers as a viable means of cosmic cleanup, the idea of laser junk removal is not new. In 2015, Japanese scientists proposed adding a trash-blasting laser to the country's Extreme Universe Space Observatory module on the International Space Station, as well as developing a new satellite-mounted laser specifically for debris removal. Using a so-called coherent amplification network laser — which focuses many small lasers into one powerful beam — the satellite could vaporize thin layers of matter off of any debris it encountered, researchers said, forcing the junk downward to burn up in Earth's atmosphere.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

China's willingness to experiment with rapid debris removal is appropriate considering that the country is considered one of the worst offenders when it comes to space junk, Universe Today reported. In 2007, a Chinese anti-satellite missile test was responsible for what is considered the most severe fragmentation of space junk in history, Space.com previously reported. The incident spewed thousands of new pieces of junk into low Earth orbit, one of which appeared to damage a Russian spacecraft in 2013.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus