Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Sizable deposits of water ice lurk just beneath the surface in some regions of Mars, a new study reports.

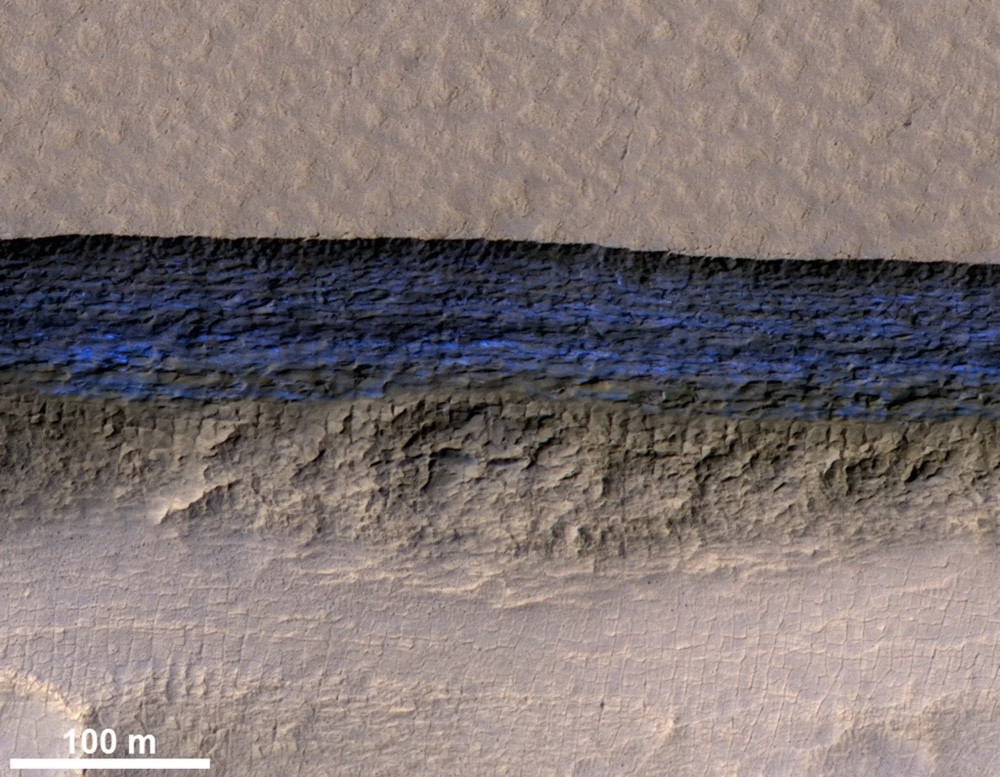

The newfound sheets appear to contain distinct layers, suggesting that studying them could shed considerable light on the Red Planet's climate history, researchers said. And the ice is buried by just a few feet of Martian dirt in places, meaning it might be accessible to future crewed missions.

"I'm not familiar with resource-extraction technology, but this may be information that's useful to people who are," study lead author Colin Dundas, of the U.S. Geological Survey's Astrogeology Science Center in Flagstaff, Arizona, told Space.com. [Photos: The Search for Water on Mars]

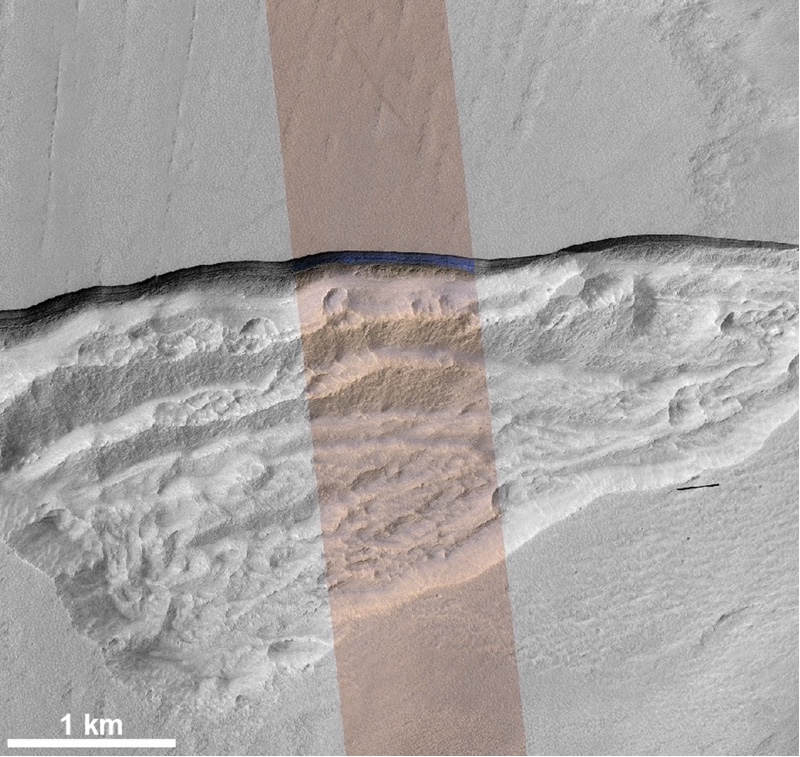

Dundas and his colleagues analyzed photos captured over the years by the High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) camera aboard NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO). They identified eight locations where erosion had exposed apparent glaciers, some of which extend 330 feet (100 meters) or more into the Red Planet's subsurface.

These sites are steep, pole-facing slopes in Mars' midlatitudes, between about 55 and 60 degrees both north and south of the equator. The ice-harboring areas sport few craters, suggesting they're quite young, geologically speaking, the researchers said.

Interestingly, scientists think that Mars' obliquity — the tilt of the planet's axis relative to the plane of its orbit — has shifted a fair bit over the past few million years, varying between about 15 and 35 degrees, Dundas said. (The Red Planet's obliquity is currently about 25 degrees; Earth's is 23.5 degrees.)

"There've been suggestions that, when there's high obliquity, the poles get heated a lot — they're tilted over and pointed more at the sun, and so that redistributes ice toward the midlatitudes," Dundas said. "So, what we may be seeing is evidence of that having happened in the past."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers already knew that Mars harbors subsurface water ice, and lots of it. For example, MRO's ground-penetrating Shallow Radar instrument recently found a buried ice layer that covers more ground than the state of New Mexico. (NASA's Phoenix lander also dug up some ice near the Martian north pole in 2008, but it's unclear if that stuff is part of a big sheet.)

But the newly analyzed HiRISE data give researchers more detailed looks at such deposits, Dundas said.

"The take-home message is, these are nice exposures that teach us about the 3D structure of the ice, including that the ice sheets begin shallowly, and also that there are fine layers," he said.

The new study was published online today (Jan. 11) in the journal Science.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus