Intricately Carved Gemstone Found in Ancient Warrior's Tomb

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

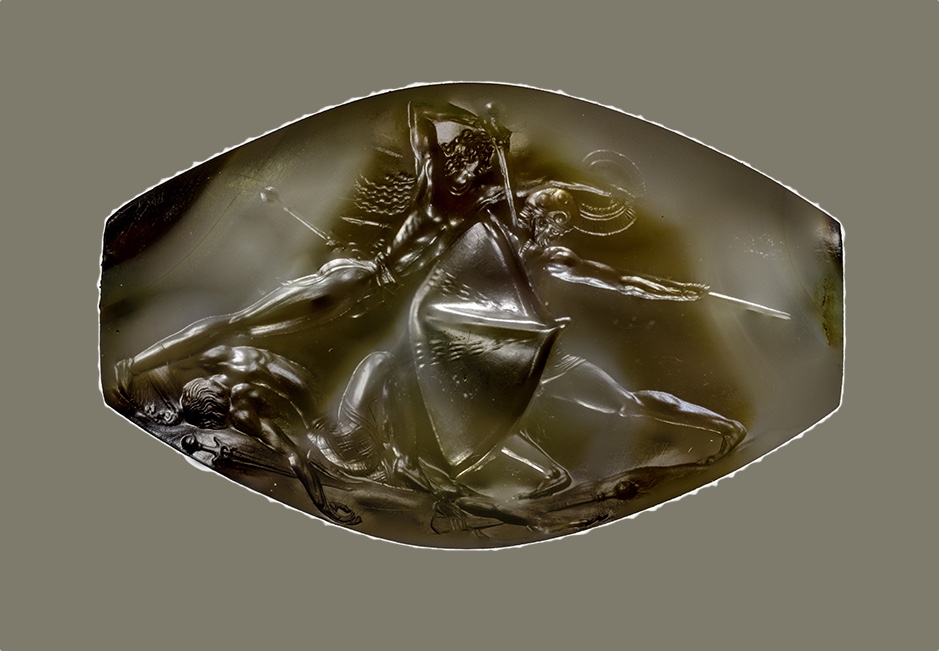

An intricately carved gemstone found in an ancient Greek tomb depicts a warrior standing over the body of a slain enemy, plunging his sword into another soldier's neck — all on less than an inch and a half of space.

The discovery comes from a tomb discovered in 2015 in Pylos, Greece, which contained the 3,500-year-old skeleton of a man dubbed the "Griffin Warrior." The tomb was filled with valuables, including an ivory plaque sporting a griffin, four gold signet rings, ivory combs and weapons. The new discovery — a sealstone, or carved gemstone — depicts a battle scene on a 1.4-inch (3.5 centimeters) piece of polished agate.

"Some of the details on this are only a half-millimeter big," Jack Davis, a professor of Greek archaeology at the University of Cincinnati and one of the researchers studying the tomb's more than 3,000 burial objects, said in a statement. "They're incomprehensibly small." [The 25 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

Detailed scene

The carved gem was encrusted in limestone and took more than a year to delicately clean, according to Davis and Sharon Stocker, another dig leader and a senior research associate in classics at the University of Cincinnati. It shows a warrior in the heat of battle in incredible detail, down to the texture of the two soldiers' hair and the muscles of their largely bare bodies.

"What is fascinating is that the representation of the human body is at a level of detail and musculature that one doesn't find again until the classical period of Greek art 1,000 years later," Davis said. "It's a spectacular find."

Many of the details require a magnifying glass, or even a microscope, to appreciate, the researchers said.

Lavish grave

The sealstone was found in a context of lavishness. The Griffin Warrior was a Mycenaean who died around 1500 B.C. His body was found in a wooden coffin, surrounded by gold, bronze and silver chalices and vessels, as well as bronze weaponry, according to the excavation team. There were hundreds of semiprecious stone beads, gold jewelry, a bronze mirror with an ivory handle, and wild-boar teeth that probably once decorated the warrior's helmet. The sealstone would have been a treasured part of this collection, Stocker said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It would have been a valuable and prized possession, which certainly is representative of the Griffin Warrior's role in Mycenaean society," she said in the statement. "I think he would have certainly identified himself with the hero depicted on the seal."

The Mycenaeans conquered the Minoan civilization on Crete, an island southeast of Pylos, between 1500 B.C. and 1400 B.C. The preponderance of Minoan-made goods in the Mycenaean tomb could indicate that rather than just straight conquest, the Minoans and Mycenaeans also participated in complex trade and cultural exchange, the researchers said. The new sealstone find also raises questions about the early development of ancient Greek art.

"It seems that the Minoans were producing art of the sort that no one ever imagined they were capable of producing," Davis said. "It shows that their ability and interest in representational art, particularly movement and human anatomy, is beyond what it was imagined to be. Combined with the stylized features, that itself is just extraordinary."

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus