New Millipede Species Has 414 Legs and 4 Penises

A pale, thread-like creature found lurking in a California cave is a brand-new species of millipede.

The stringy arthropod has 414 legs and four "penises," limbs that were converted over evolutionary time into structures that transfer sperm. Only a single specimen of the new species has been found, a male, so researchers don't know what the females look like.

The millipede hails from a marble cavern called Lange Cave in Sequoia National Park. Researchers launched a major survey of caves in Sequoia and nearby Kings Canyon National Park that lasted from 2002 to 2004, with smaller follow-up excursions running from 2006 to 2009. During one of those excursions in October 2006, cave biologist Jean Krejca, now of Zara Environmental in Texas, discovered a skinny little millipede about 0.8 inches (20 millimeters) long. Krejca sent the specimen for analysis to millipede specialists Paul Marek of Virginia Tech and William Shear of Hampden-Sydney College in Virginia. [Gallery: Extreme Close-Ups of the New Millipede]

Leggy discovery

The researchers soon realized that they had something new on their hands: a species in the genus Illacme. Only one other species of Illacme has ever been discovered, Illacme plenipes. That species came from San Benito County, California, 150 miles (240 kilometers) away from Lange Cave. With up to 750 legs apiece, I. plenipes is the leggiest millipede on the planet.

"I never would have expected that a second species of the leggiest animal on the planet would be discovered in a cave 150 miles away," Marek said in a statement.

The researchers dubbed the new species Illacme tobini, after Ben Tobin, a cave specialist at Grand Canyon National Park who organized the survey that uncovered the new millipede.

Rare find

After the discovery, researchers spent several years looking for more specimens of the new species, checking around Lange Cave and at 63 other locations in the Sierra Nevada foothills. They turned over leaf, log and rock, but found nothing.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

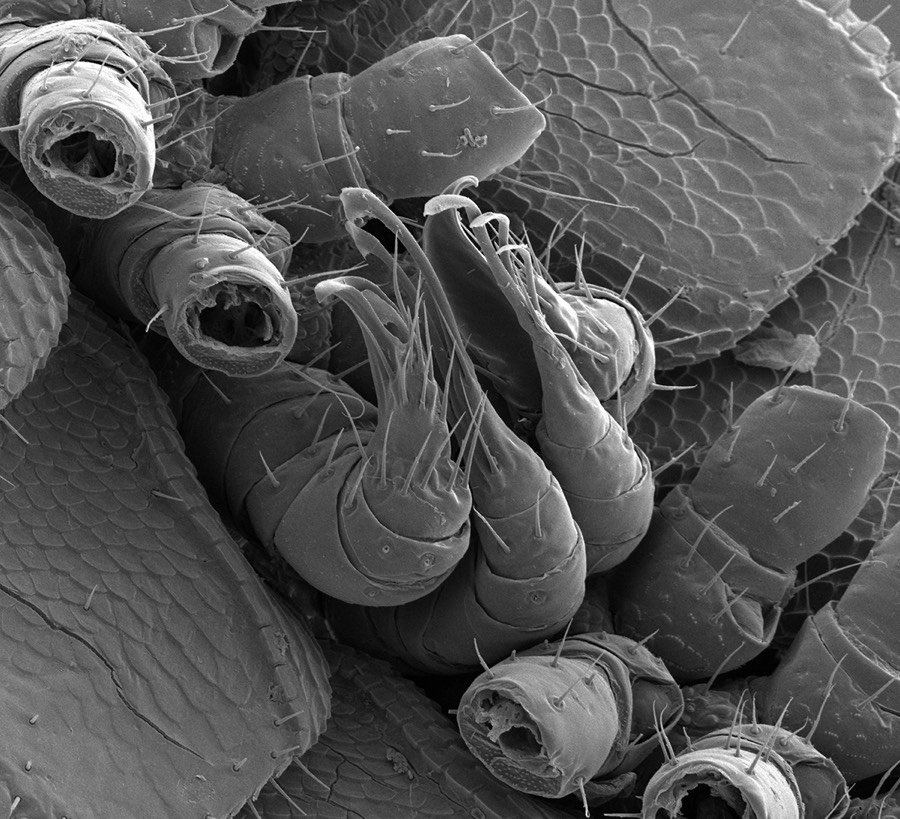

As a result, the new species is known only from the single male found in Lange Cave, a marble cavern situated in woodland habitat at the base of Yucca Mountain. The eyeless millipede may feed on fungus, the researchers wrote online Oct. 20 in the journal ZooKeys. Its ninth and 10th leg pairs have been converted into the millipede version of penises, known as gonopods. These specialty limbs are covered in spikes and shovel-like projections that shuttle sperm from male to female.

The millipede also sports 200 pores that secrete some sort of unidentified substance — perhaps a chemical defense against predators. It's unclear whether I. tobini lives solely in caves, the researchers wrote, or whether it might also be found in standard millipede hideouts like the undersides of rocks.

I. plenipes was discovered in 1928, making I. tobini only the second Illacme species ever discovered, 90 years later. Both species are members of the larger family Siphonorhinidae, a secretive group consisting of only 12 known species. Illacme are the only North American representatives, but others in the family come from Vietnam, South Africa, India, Indonesia and Madagascar. The family probably arrived at these disparate locations by spreading across the ancient supercontinent Pangea, the researchers wrote, becoming forever divided when that giant landmass broke up 200 million years ago.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.