Fish Spit to Keep Monstrous 'Sarlacc' Worms Away

Indo-Pacific fish have a cooperative defense against a real-life sarlacc: spit.

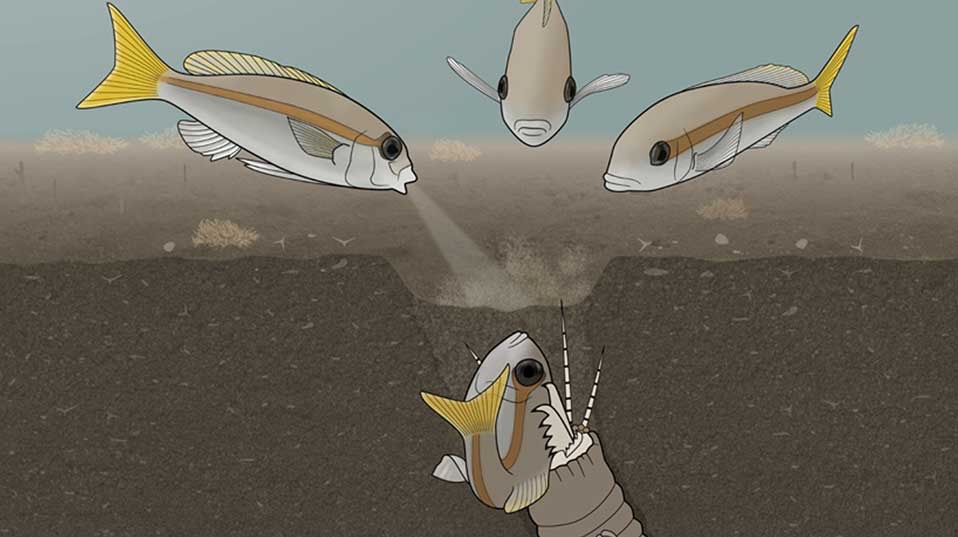

For the first time, researchers have observed small fish mobbing up against a worm that hunts like the Star Wars predator made famous in "Return of the Jedi." The giant Bobbit worm (Eunice aphroditois) buries its 10-foot-long (3 meters) bulk in the sandy seafloor, waving wormy antennae in the water and dragging passing fish into its den.

A single small fish is no match for this predatory monster, but a white-and-yellow species called Peters' monocle bream (Scolopsis affinis) gangs up to defend itself against the Bobbit worm, researchers reported Sept. 12 in the journal Scientific Reports. In doing so, it also alerts other fish to the worm's location, ruining the predator's chances for a meal.

"Concerning their mental capacity, fish are for the most part greatly underestimated," study researcher Daniel Haag-Wackernagel, a biologist at the University of Basel, said in a statement. Research into their behavior in their natural habitats continues to reveal big surprises." [See Photos of a Worm with 5 Shape-Shifting Mouths]

The Bobbit worm is an annelid, or segmented worm. It attacks its prey with sharp teeth and a toxin that can stun. As fearsome as they are, these worms don't move around much. They rely on the element of surprise to catch prey (and are much more subtle than the Star Wars sarlacc, which relied on the enemies of Jabba the Hutt to stay well-fed).

When Peters' monocle bream detect a Bobbit worm, they respond by hovering right over the entrance to the worm's burrow and spitting jets of water at the worm. When one bream starts this behavior, other breams join in, a phenomenon called "mobbing." Mobbing occurs when prey animals team up to drive off a predator. Birds do it frequently. Starlings, for example, will team up to dive-bomb hawks or owls to keep from being picked off, according to the Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife.

The spitting fish drive the Bobbit worm back into its burrow, and might also mark the spot as dangerous so that the school can avoid it in the future, the researchers wrote. Though the fish sometimes mobbed a worm after the worm snatched one of their shoalmates, the researchers didn't see any fish get attacked during mobbing. Because Bobbit worms prefer to surprise their prey, it's probably not too dangerous for the fish to participate in the mob, the researchers wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study took place in the Lembeh Strait near Indonesia. The researchers dove to the black-sand bottom 90 times to observe four different Bobbit worms and the fish that inhabited the territory. In one case, a second species of bream, the monogrammed monocle bream (Scolopsis monogramma), joined the Peters' monocle breams in shooting water at the worm.

"This astonishing observation may indicate that mobbing by directing water jets to an ambushing enemy is more widespread," the researchers wrote.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus