Bunnies Were Butchered at Ancient City of Teotihuacan

Humans may have raised rabbits and hares in Mexico's ancient city of Teotihuacan — but not to keep them as pets.

The bunnies were probably butchered 1,500 years ago for their meat, hide and fur, according to new research.

"Because no large mammals such as goats, cows or horses were available for domestication in pre-Hispanic Mexico, many assume that Native Americans did not have as intensive human-animal relationships as did societies of the Old World," study author Andrew Somerville, an anthropologist at the University of California, San Diego, said in a statement. Somerville's study, published today (Aug. 17) in the journal PLOS ONE, might change that perception. [In Photos: Human Sacrifices Discovered in Ancient City of Teotihuacan]

Bunny shop

Teotihuacan, about 30 miles (50 kilometers) northeast of modern-day Mexico City, was a sprawling city that flourished between about 2,100 years ago and 1,400 years ago. Built on a grid, the city might be most famous for its monumental pyramids, but Teotihuacan also had vast domestic complexes.

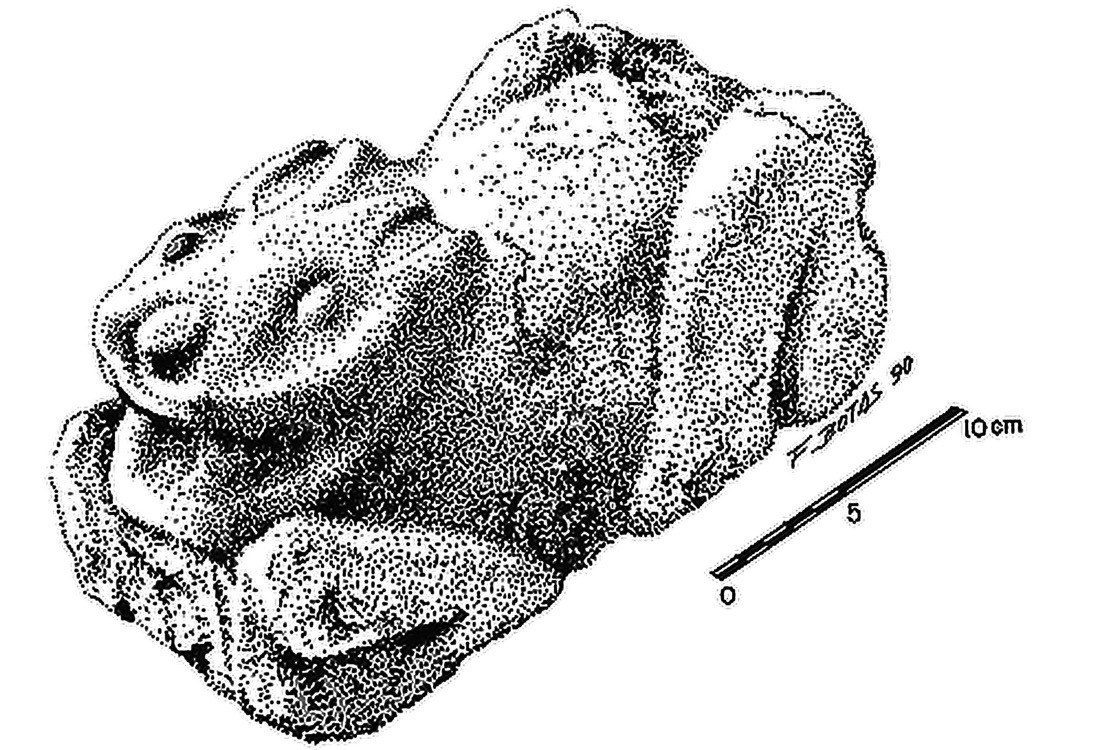

Inside one of these compounds, Oztoyahualco — which was used during the city's Xolalpan phase (A.D. 350-550) — scientists found a high concentration of bones from cottontails and jackrabbits (collectively known as leporids, the family that includes rabbits and hares).

Some of the rooms in this complex showed traces of animal butchering, including signatures of feces and blood in the soil, large collections of sharp obsidian blades, and a ground stone that was possibly used for cutting hides. A stone sculpture of a rabbit was even found in one of the courtyards of the complex.

To confirm that the animals were being intentionally bred by humans, Somerville and his colleagues tried to reconstruct the rabbits' diet, by looking at isotope concentrations in the ancient bones.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rabbit food

Isotopes are variations of chemical elements. The concentration of certain isotopes in skeletal remains can reveal what types of food animals ate and where they lived. The same type of technique has been used to reveal that Britain's King Richard III ate game birds and drank wine, and that the first settlers of Sicily avoided seafood.

The researchers examined a total of 134 rabbit and hare bone samples from Teotihuacan, including 17 from the Oztoyahualco compound. They also looked at 13 bone samples from modern specimens in central Mexico.

Compared to modern wild specimens, the rabbits and hares from Teotihuacan had carbon isotope ratios that suggested they ate more human-farmed crops, such as maize and nopal cactus, the study found. What's more, the specimens from Oztoyahualco had the strongest signatures of human-farmed food in their diet.

Somerville and his colleagues speculated that humans and rabbits might have once had a hunter-prey relationship, with the rabbits raiding crops in Teotihuacan and humans hunting them in their gardens. But this relationship may have eventually given rise to "active management and controlled reproduction," with humans feeding the rabbits as they bred them to be used for food and their other products, such as fur, the authors of the study wrote.

"Our results suggest that citizens of the ancient city of Teotihuacan engaged in relationships with smaller and more diverse fauna, such as rabbits and jackrabbits, and that these may have been just as important as relationships with larger animals," Somerville said in the statement.

Archaeologists are interested in evidence of animal domestication because it can signal other developments in complex society, and new discoveries can illuminate some surprising human-animal relationships, beyond the farmer-livestock one. Bird mummies, for instance, suggest that ancient Egyptians may have practiced falconry. And bones found in prehistoric villages in China suggest that farmers may have domesticated wild Asian leopard cats to keep as pets more than 5,000 years ago.

Original article on Live Science.