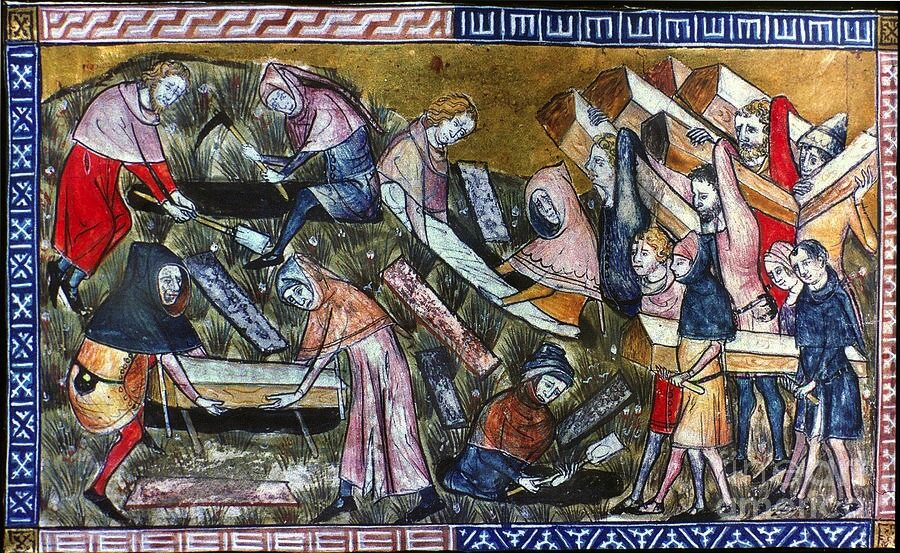

Black-Death Survey Reveals Incredible Devastation Wrought by Plague

The devastation wrought by the Black Death plague pandemic in medieval England has been revealed in a uniquely detailed archaeological study carried out for more than a decade with the help of thousands of village volunteers.

Although some historians have played down the impact of the bubonic plague that struck Europe and Asia in the 1300s, new research shows that the Black Death was as deadly as described in writings that have survived from the time, with some villages suffering an almost 80 percent drop in population after the plague.

The study gathered and analyzed data about broken pieces of domestic pottery found in more than 2,000 test pits measuring 11 square feet (1 square meter) at the surface and up to 4 feet (1.2 meters) deep that were dug in 55 villages in eastern England. [See Photos of How Archaeologists Tracked the Impact of the Black Death]

The test pits were excavated from 2005 to 2014 by an estimated 10,000 volunteers, including students, homeowners and local community groups, under supervision by archaeologists and trained local team leaders. Each of the villages in the survey is known to have been occupied before the Black Death, which by some estimates killed more than 3 million people in England between 1346 and 1351.

In most of the surveyed villages, the quantities of pottery pieces indicate sharp long-term falls in population from the time of the Black Death. Many village populations did not recover until about 200 years later, in the 16th century.

Seeing the big picture

The new study has been able to map, for the first time, how different communities were affected by the plague. Overall, the population of the surveyed villages fell by an average of 45 percent after the Black Death. One of the worst-hit villages, Pirton in Hertfordshire, suffered a 76 percent drop in population. But a few villages seem to have survived almost unscathed.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States, the Black Death killed between 75 million and 200 million people in Europe and Asia after its appearance in central Asia early in the early 14th century, and reached its peak in Europe, where it killed up to 60 percent of the population.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Study leader Carenza Lewis, an archaeologist at the University of Lincoln in the United Kingdom, told Live Science that the quantity of dated pottery pieces found at different depths in each test pit served as an indicator, or proxy, for the human population of the sites at different times.

"Human communities in this part of the world are using pottery consistently through the medieval period," Lewis said. "Pottery is cheap to buy, so everyone has it. It's easy to break, and when it's broken, you throw it away rather than trying to mend it, because it's cheap. And when you've thrown it away, it doesn't rot, so it just sits there forever."

Pottery and population

Although gathering data about pottery from test pits had been done at single sites before, this study was the first time that so much data from so many sites were brought together to provide an overall picture of population changes. [In Photos: 14th-Century 'Black Death' Grave Discovered]

The multiple test pits dug at each of the 55 villages in the study resulted in more accurate data, Lewis added.

"This is a completely different approach — just scatter-gunning these villages with these test pits," she said. "Each pit is like one piece of a jigsaw puzzle that you can just put in place."

Lewis said the results clearly showed the "eye-watering" impact of the Black Death on the region, contrary to some recent studies that have suggested that historical accounts of the plague's devastation were exaggerated.

"There's been a prevailing view in the second half of the 20th century that these kinds of epidemic diseases were quite widespread, and that communities recovered pretty quickly," Lewis said. "I think it was just rather unfashionable to think that something as dramatic as the Black Death could have had such an impact."

The results of the latest study, however, clearly show otherwise.

"We can't identify whether these people died of the plague or whether they just moved away to a better place because someone else had died of the plague and a better place became available," Lewis said. But "what we definitely see is that the overall volume of pottery in use drops by 44 to 45 percent in a long-term, sustained drop, and we can see that some communities were much worst hit than others," she said.

Incredible devastation

Lewis said the findings support the emerging consensus that the population of England remained between 35 and 55 percent below its pre-Black Death levels well into the 16th century. [Pictures of a Killer: A Plague Gallery]

She added that several villages in the county of Norfolk, in the northern part of the study area, had suffered up to an 80 percent decline in population, according to the analysis of the pottery.

Yet, a few villages in Suffolk, in the southern part of the study area, actually saw an increase in population over the same time.

"Now, we can see what the change is; we can now start to work out why it happened," Lewis said. "And it looks like agricultural villages were particularly badly hit because agriculture is labor-intensive, and when the population drops, the availability and cost of labor is high. So, what we see is the economic bottom line for agriculture becomes very unsustainable."

In the Suffolk villages where the population actually increased, though, these "seem to be villages that were tied into the cloth trade, which was very profitable," Lewis said.

"Today, these villages are just somewhere nice to live, but in the medieval period, they were like small businesses — they've got to be able to sustain themselves, and if they're not sustainable, they collapse," she added.

In the new study, Lewis noted the potential for the test-pit data technique to be extended to other areas.

"This new research suggests there is an almost unlimited reservoir of new evidence capable of revealing change in settlement and demography still surviving beneath today's rural parishes, towns and villages — anyone could excavate, anywhere in the U.K., Europe or even beyond, and discover how their community fared in the aftermath of the Black Death," she wrote in the study.

The new study was published online May 17 in the journal Antiquity.

Original article on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.