In Photos: The Spectacular Migration of Monarch Butterflies

The migration of animal species is a common natural event that happens each autumn across the North American continent. Many species of birds and even mammals, such as the great whales, travel thousands of miles to over-winter in warmer climates. Check out these photos of one of the most spectacular migrations.

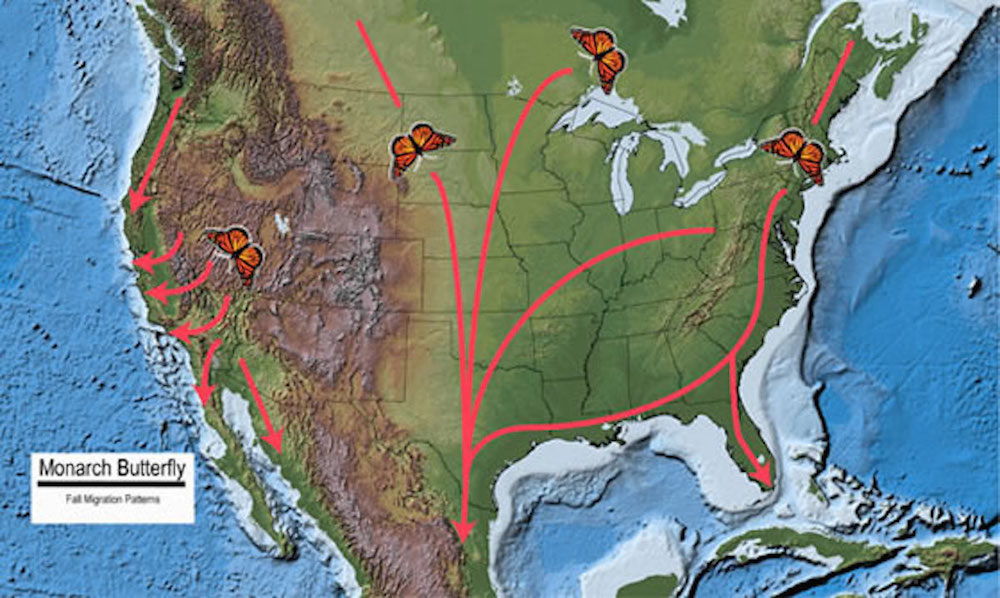

Mass migration

Surely one of the most unique and amazing migration events occurs each autumn when thousands and thousands of monarch butterflies (Danaus plexipus) migrate to the warm mountains of central Mexico and the coastal regions of southern California. (Credit: NPS)

Getting to know this beauty

Monarch butterflies are tropical insects. Their home range extends as far north as Canada. They may be the most recognized of all butterflies, with their beautiful and distinct orange, white and black wings. The insects range throughout Canada, the United States and Mexico. During their larvae stage, the monarch caterpillar feeds almost exclusively on the common milkweed plant (Asclepius syriaca), while adult butterflies feed upon the nectar of flowers. (Credit: NPS)

Unique among their kind

Monarch migration is unique to all butterflies found in North America. Some individual butterflies travel upwards of 3,000 miles (4,830 kilometers) and can fly at altitudes as high as 10,000 feet (3,050 meters). They are the only butterfly species to make such a long, two-way migration every year. Their offspring return each winter to the same winter roosts and even to the same trees used by previous monarch generations. (Credit: NPS)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Wintering in Mexico

If the monarch butterfly has spent the summer east of the Rocky Mountains, it will travel to the Sierra Madre Mountains of Mexico. Here, they are known as Mariposa monarca and will spend the winter days from October to late March in the warm, unique habitat of oyamel fir trees (Abies religiosa). (Credit: USDA)

Wintering in the Golden State

If the monarch butterfly has spent the summer west of the Rocky Mountains, it will travel a shorter distance, to the many groves of Monterey pine (Pinus radiaita), Tasmanian bluegum eucalyptus (Eucalyptus globulus) and Monterey cypress (Cupressus macrocarpa) found along the coasts from northern to southern California. (Credit: NPS)

Family secrets

All monarch butterflies seems to use environmental clues to stimulate the beginning of their annual journey. It is speculated that the shortening length of daylight and cooler temperatures play a role in the beginning of the migratory journey. The position of the sun in the sky and the magnetic pull of the Earth may both aid in the butterflies' accurate navigation. Monarchs will travel to the very same trees each year, which is an amazing fact of nature when one realizes that they are not the same butterflies that used the tree the previous winter. In fact, they are three to four generations removed from the previous winter’s butterflies. (Credit: NPS)

Finding shelter on the road

Monarchs have been known to travel between 50 to 100 miles (80 to 160 km) each day. The long journey can take upwards of two months to complete. One tagged monarch butterfly was recorded to have traveled some 265 miles (430 km) in just one day. Since monarchs only travel during the daylight hours, they must find protective environments in which to roost each night of their journey. Some such roosting sights are known to be used year after year by the migrating monarch butterflies. (Credit: NPS)

Power of the masses

Once they reach the trees in which they will over-winter, the monarch butterflies will cluster together to stay warm. Tens of thousands of beautiful orange butterflies can cluster together on a single tree. Even though a single monarch weighs less than fractions of an ounce, the massive cluster of butterflies exert a heavy weight on tree branches, which sometimes break from the combined weight of the butterflies. (Credit: Linda & Dr. Dick Buscher)

Winter cluster

One of the largest colonies of monarch butterflies found along the California coastline is found in the quaint and classic beach town of Pismo Beach. The butterflies begin arriving at their winter home in mid-October, allowing visitors to leisurely walk beneath the branches of a small grove of eucalyptus trees and gaze upon some 25,000 beautiful butterflies clinging to the leaves and branches. (Credit: Linda & Dr. Dick Buscher)

A long winter's nap

During the long winter months, the thousands of monarch butterflies remain relatively inactive, living on their stored fat reserves. During a warm, sunny day, individual butterflies will flutter about or be seen on the ground, basking in the warm sunlight. The Pismo Beach monarchs will remain in the eucalyptus grove until late February, when they become active again and begin the migratory journey north. (Credit: Linda & Dr. Dick Buscher)

Vulnerable and protected

Since monarch butterflies only over-winter in a few locations, they are extremely vulnerable to any unusually cold weather at those sites that can kill thousands of them. So, too, do they face great danger from the destruction of their habitats from human activities. Most of the large monarch over-wintering sites along the California coastline are now protected as monarch sanctuaries. (Credit: Linda & Dr. Dick Buscher)

Generation after generation

When the warm weather and lengthening daylight hours arrive again with a new spring, the monarch butterflies of Pismo Beach will become active again. They soon become reproductive and begin laying their eggs, giving rise to a new generation of caterpillars and soon-to-be adult butterflies. Unlike their parents, who made the migration to the south and west, this generation of monarch butterflies will make their migratory journey back to the east and north. (Credit: NPS)

Breathtaking wonder

The migration of the monarch butterflies is certainly one of nature's most amazing phenomenons, and is made even more special by the monarch sanctuaries along the California coastline that welcome visitors to see, learn and enjoy all about these beautiful creatures of our natural world. (Credit: Linda & Dr. Dick Buscher)

Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus