WWII Ship Used for Atomic Bomb Tests Found 'Amazingly Intact'

The USS Independence aircraft carrier, which operated during World War II, has been located about a half mile underwater off California's Farallon Islands.

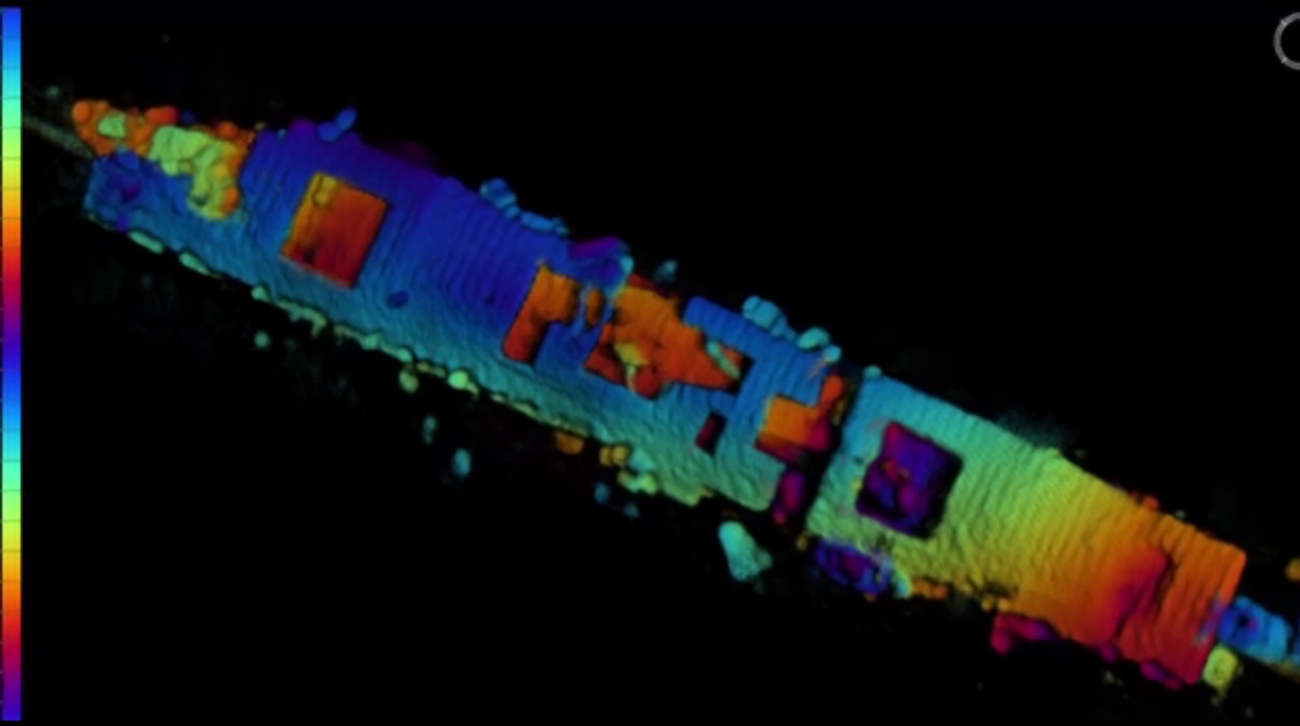

Using an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) dubbed the Echo Ranger and a 3D-imaging sonar system, researchers have created a detailed picture of the 622-foot-long (190 m) ship, revealing that it is "amazingly intact," said scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The 3D images also showed what appears to be a plane in the carrier's hangar, the researchers noted.

"After 64 years on the seafloor, Independence sits on the bottom as if ready to launch its planes," James Delgado, chief scientist on the Independence mission, said in a statement. "This ship fought a long, hard war in the Pacific and, after the war, was subjected to two atomic blasts that ripped through the ship. It is a reminder of the industrial might and skill of the 'greatest generation' that sent not only this ship, but their loved ones to war," added Delgado, maritime heritage director for NOAA's Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. [See Images of the USS Independence Shipwreck and Dive Mission]

After operating in the Pacific Ocean from November 1943 to August 1945, the carrier became one of 90 vessels in a target fleet for atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean in 1946. Called Operation Crossroads, the project consisted of two atomic bomb tests: an airstrike and an underwater strike meant to reveal the effects of a nuclear explosion on a naval fleet, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). (The tests continued until 1958 and included the explosion of the first hydrogen bomb in 1952, according to UNESCO.)

The USS Independence, like dozens of ships involved in Operation Crossroads, was damaged by the shock waves, heat and radiation from the tests and ultimately was sent back to U.S. waters. While the Independence was moored at San Francisco's Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, the U.S. Navy ran decontamination studies on it. Then, on Jan. 26, 1951, the U.S. Navy towed the carrier out to sea and sank it, according to the NOAA statement.

The U.S. Navy, after sinking the ship, documented its location, but those numbers weren't exact and the different entries varied from one another, with one suggesting the USS Independence was 300 miles (480 kilometers) off the coast, Delgado said. In actuality it is 30 miles (48 km) off the coast.

NOAA's most recent multibeam echo-sounding survey, which was from the water's surface, revealed "something big" down there; but from so far away the pictures were "pixelated," Delgado said. "It really looked like a big fuzzy caterpillar stretched out on the bottom," Delgado told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To figure out if the "caterpillar" was the USS Independence, last month, NOAA scientists, in collaboration with Boeing, completed sonar imaging closer to the wreck. The endeavor was part of a two-year mission to find, map and study the 300 or so historic shipwrecks in and around the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary. The team used the Echo Ranger, Boeing's 18.5-foot-long (5.6 m) underwater bot, outfitted with an integrated 3D-imaging sonar system provided by tech company Coda Octopus.

Aboard the R/V Fulmar research vessel, scientists followed the autonomous underwater vehicle as it glided 150 feet (45 m) above the Independence wreck, located beneath 2,600 feet (790 meters) of water.

"We imaged the same spot on that shipwreck multiple times; that gives us very, very high definition," Blair Cunningham, technology president at Coda Octopus, said in a NOAA video.

Results showed that the carrier is upright, slightly tilted toward the starboard, or right side, and that much of the hull and flight deck are intact. But there was damage to the ship from the testing.

"The sonar images showed the damage the Navy had initially documented is still very much there, the flight deck has been distorted. Some of the areas of the flight deck have started to collapse and there are holes in the deck," Delgado said.

Also, some of the radiation — in the form of fission fragments from the decay of plutonium-239, a radioactive isotope of plutonium — from those blasts can still be found in the ship, the researchers noted. "The ship was partially decontaminated, but some of the fission fragments are expected to be still bound to the ship," said Kai Vetter, a nuclear physicist at UC Berkeley, who is involved in the project. [Facts About Hiroshima, Nagasaki & the First Atomic Bombs]

"Even if some of the radioactive materials 'leaked' or still 'leak' from the ship, this radioactivity will be diluted very quickly in the water reducing the concentration substantially," Vetter told Live Science. "In addition, the radiation emitted by the radioactive materials on the ship will not travel very far as the water is an excellent shield."

As the ship's metal corrodes, the associated chemical reactions can cause some of the radioactive material to leak into the water, added Vetter, who is also at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

The researchers are interested in studying the long-term effects of the changing radioactivity on the ship. "We are considering to get closer to the ship next time and to potentially remove some parts of the ship for further analysis in our labs," Vetter said. That closer look would require more safety precautions to ensure no radioactive contamination of the people or equipment, he added.

Follow Jeanna Bryner on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.