Cold Air Invasion Coming: What’s the Role of Warming?

Get ready for the invasion — of cold air.

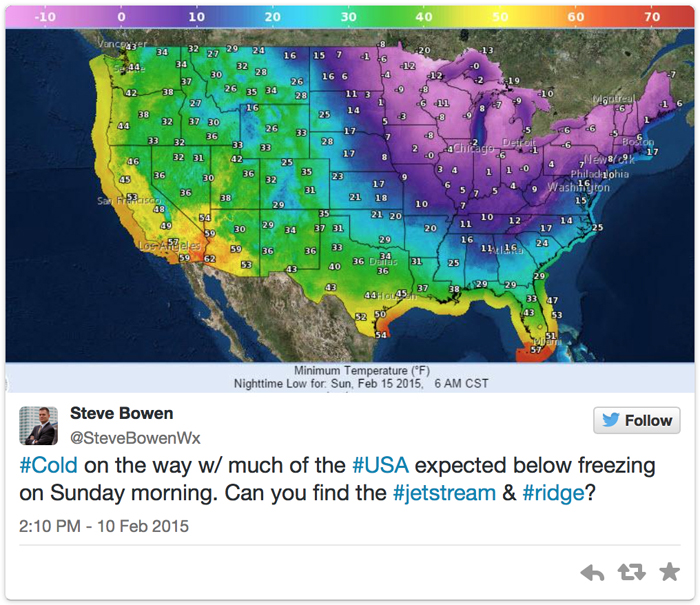

Temperatures are set to drop to levels that are low even for the middle of winter across the eastern U.S. starting Thursday and again over the weekend as Arctic air makes repeated surges southward. Temperatures Sunday morning could be below freezing as far south as Florida.

This pattern may sound familiar to those in the eastern U.S. who shivered under repeated such incursions last winter, when the term “polar vortex” became all the rage. The non-stop sucker punches of frigid air also brought to the forefront the idea that global warming could paradoxically be behind them, with Arctic sea ice melt forcing wild dives in the jet stream up in the atmosphere.

But it’s a hotly debated idea that has spurred a flurry of research, some of which bolsters the connection but still leaves key questions unanswered and many atmospheric scientists skeptical.

Cold Nights Are Decreasing Across the U.S. What A Warming World Means for Major Snowstorms Warming Ups Odds of Extreme La Niñas, Wild Weather

And of course linking any Arctic outbreak, just like any other singular weather event, to the effects of warming is difficult, at best. And in this particular case, experts cited different reasons for the return of the intruding Arctic air.

What Will Happen

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Later this week and over the weekend, two surges of frigid air originating in the polar regions will push their way southward over the eastern half of the country. The second bout will be the more teeth-chattering of the two and there’s some potential for record-cold temperatures, though not nearly as cold as models initially suggested a few days ago.

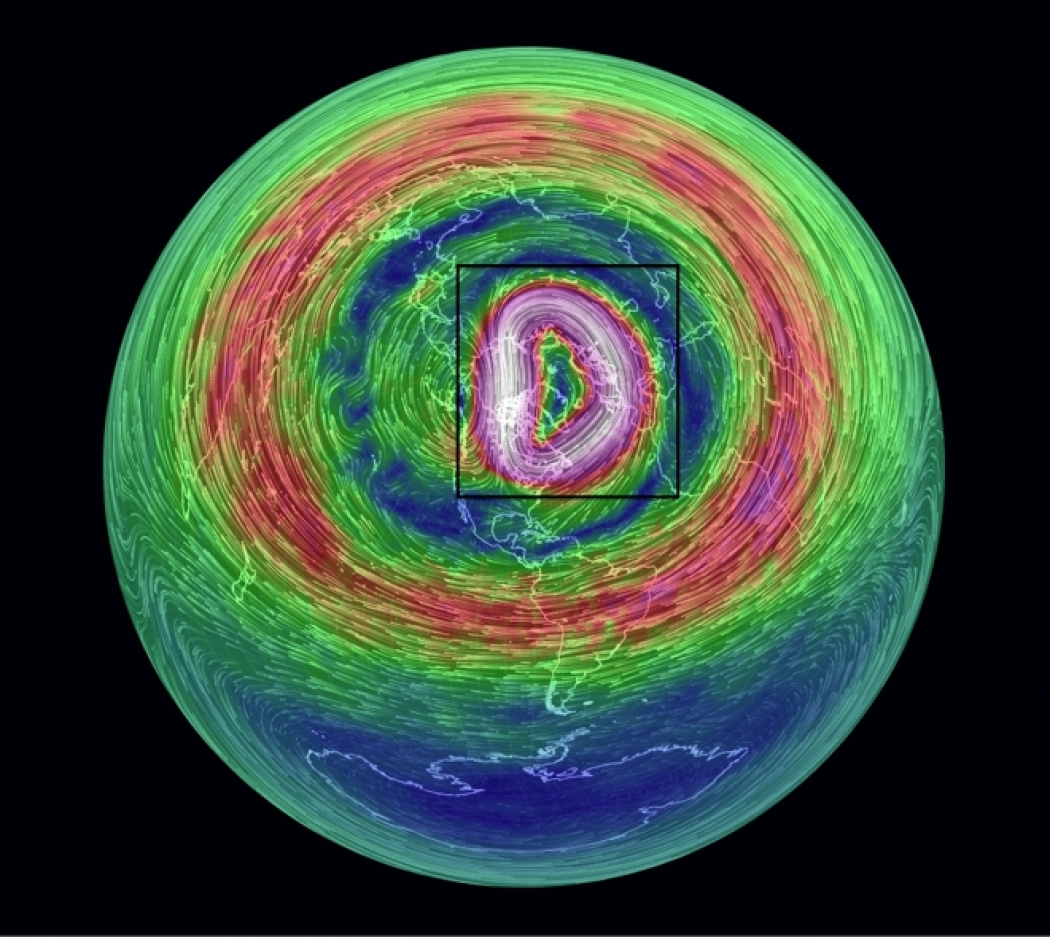

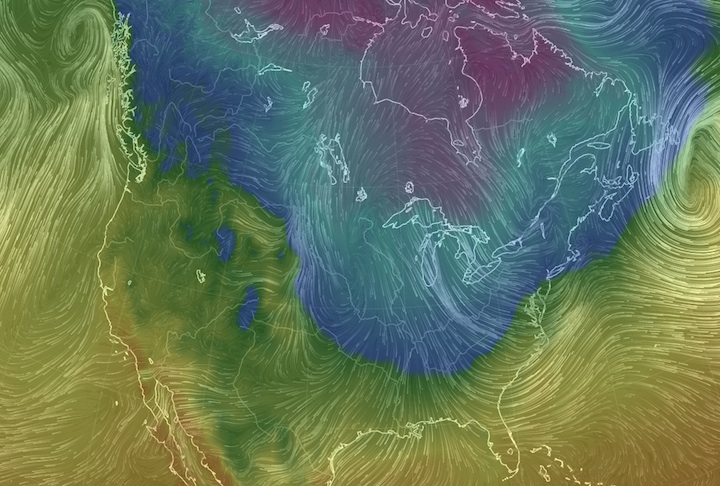

But just to be clear, while the cold invasion is linked to the polar vortex, the actual polar vortex isn’t relocating. That vortex is, more or less as its name implies, a circular pattern of fast-moving winds around the North Pole that when it is strong keeps the coldest of the cold air hemmed in. Usually the vortex is at its most robust in the winter — when the large difference between temperatures from the equator to the pole makes for the strongest winds. But it can, and does, weaken, allowing that cold air to make a break for it and spill southward.

“Call it a kink in the jet stream that’s allowing some pure Arctic air to come down,” climatologist Mike Halpert of the Climate Prediction Center said. “It’s not like the polar vortex has shifted and it’s sitting over Boston.” (Halpert, for the record, is not a fan of the polar vortex term because of how often it is misused; it “makes the hairs on my neck stand up,” he said.)

Some researchers suggest that such kinks in the jet stream that allow that cold air to spill out could actually become more common in a warming world because of changes to the environment where that cold air originates — the Arctic.

Warming’s Weird Effects

Rutgers University sea ice researcher Jennifer Francis was one of the first to suggest a link between the steady decline of Arctic sea ice caused by warming and the extreme twists and turns that the jet stream — the fast-moving river of air miles up in the atmosphere — can take northward and southward. (At the same time that a dip in the jet stream sends polar air southward, a corresponding ridge can push warmer conditions up into the Arctic.)

The idea is that as white, reflective sea ice has been increasingly melting to lower and lower areas in the summer, there is more dark, open ocean that can absorb the sun’s rays. As sea ice begins to reform as fall progresses, the water releases that heat into the atmosphere. That added heat could be pushing atmospheric patterns in a way that destabilizes the polar vortex and makes the jet stream behave more wildly.

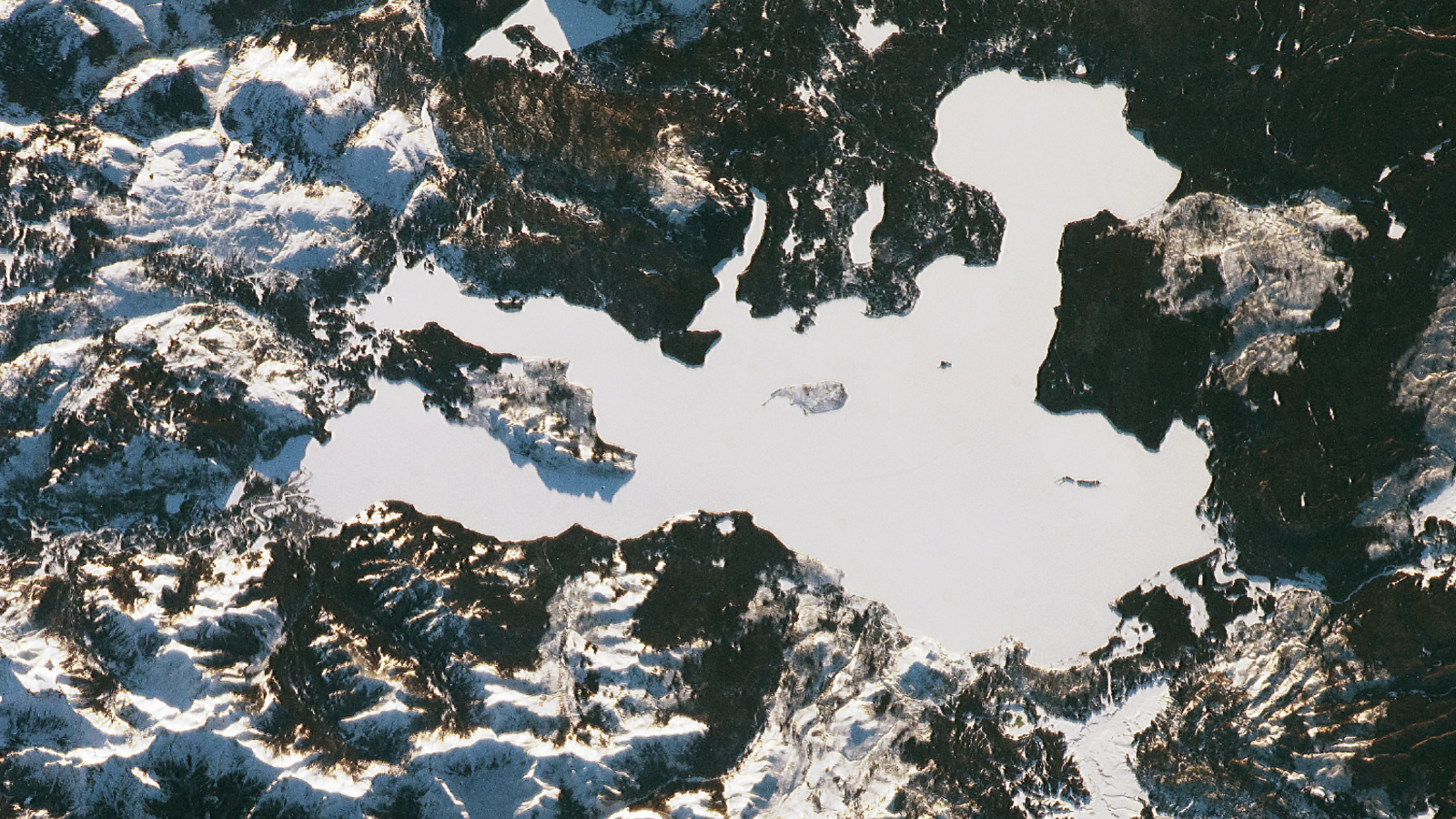

Research efforts using climate models have found matches between sea ice loss in certain regions and cold outbreaks. In particular, several have suggested that when sea ice is low in the Barents and Kara seas (to the north of Siberia) cold air does later dip down substantially over parts of Europe and Asia in the fall and winter.

Another recent study, presented last month at the annual meeting of the American Meteorological Society by Lantao Sun of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, further suggested that the region where the low ice levels are in the winter can affect how much heat moves upward into the atmosphere during that season. The degree of heat transport in turn could determine whether the jet stream responds.

“We're learning that there are different mechanisms at play in different regions and seasons,” Francis said.

But these modeling efforts are ahead of the actual observations (which cover too short a time span to see any definitive relationship), and many people who study the dynamics of the atmosphere are dubious about the connection.

“If the modelers can come up with some compelling mechanisms that link surface changes in the Arctic to large-scale circulation changes, then it will be a feather in their cap,” John Walsh of the International Arctic Research Center at the University of Alaska Fairbanks said. Walsh was one of several atmospheric scientists who published a letter in the journal Science a year ago noting their skepticism of the sea ice-jet stream link.

The main thing needed to perhaps bring both sides together is that favorite refrain of scientists: more research.

“Scientists’ opinion on the influence of Arctic Amplification on mid-latitude weather is fairly polarized, but I am optimistic that further study of the subject will yield better clarity and consensus in the next few years,” Judah Cohen, an atmospheric scientist with Atmospheric and Environmental Research who has also done research on the topic, said.

What’s Behind This Event

While scientists are actively looking into the ways warming might influence winter cold snaps in the future, there’s less they can say about what’s behind particular patterns and outbreaks now.

“Explaining why something happened is almost as hard as predicting it,” Halpert said.

Francis and Walsh both say that the dips the jet stream is taking now are in line with the idea she and others have laid out. But actually naming that as the cause is another story.

“Sea ice extents have been running near record-low values all winter. I can't say this is the cause, but it is certainly consistent with our hypothesis,” Francis said.

Cohen, on the other hand, doesn’t think this year isn’t a good example of the effects they expect from sea ice melt because sea ice coverage in the Barents and Kara seas has been around normal.

“My own analysis supports the idea that sea ice and Arctic amplification can influence our weather,” Cohen said. “However, not every time it is cold or extreme weather occurs, can it be attributed to sea ice melt or even Arctic amplification.”

Cohen thinks this cold outbreak is due to unusually high snowfall cover over Siberia back in the fall. That large area of snow may have triggered the transfer of energy from the lower layer of the atmosphere, the troposphere, to the one above it, the stratosphere, causing a destabilization of the polar vortex and letting the cold air out of its polar pen.

And, of course, the natural fluctuations of the atmosphere could also be playing a role in the cold outbreaks of this winter and last. A series of bitter cold winters was also seen back in the late 1970s, Walsh pointed out, so this could be another example of random shifts.

The bottom line, according to Halpert: “It’s winter and that’s when cold weather happens.”

You May Also Like: Warmer Seas Linked To East Coast Hurricane Outbreaks Paris Talks Won’t Achieve 2°C Goal: Does That Matter? Is pH a Red Herring for Ocean Acidification? Geoengineering Holds Promise; Solutions Not Ready

Original article on Climate Central.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.