Kilauea Lava Flow Consumes Cemetery, Reaches Town

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

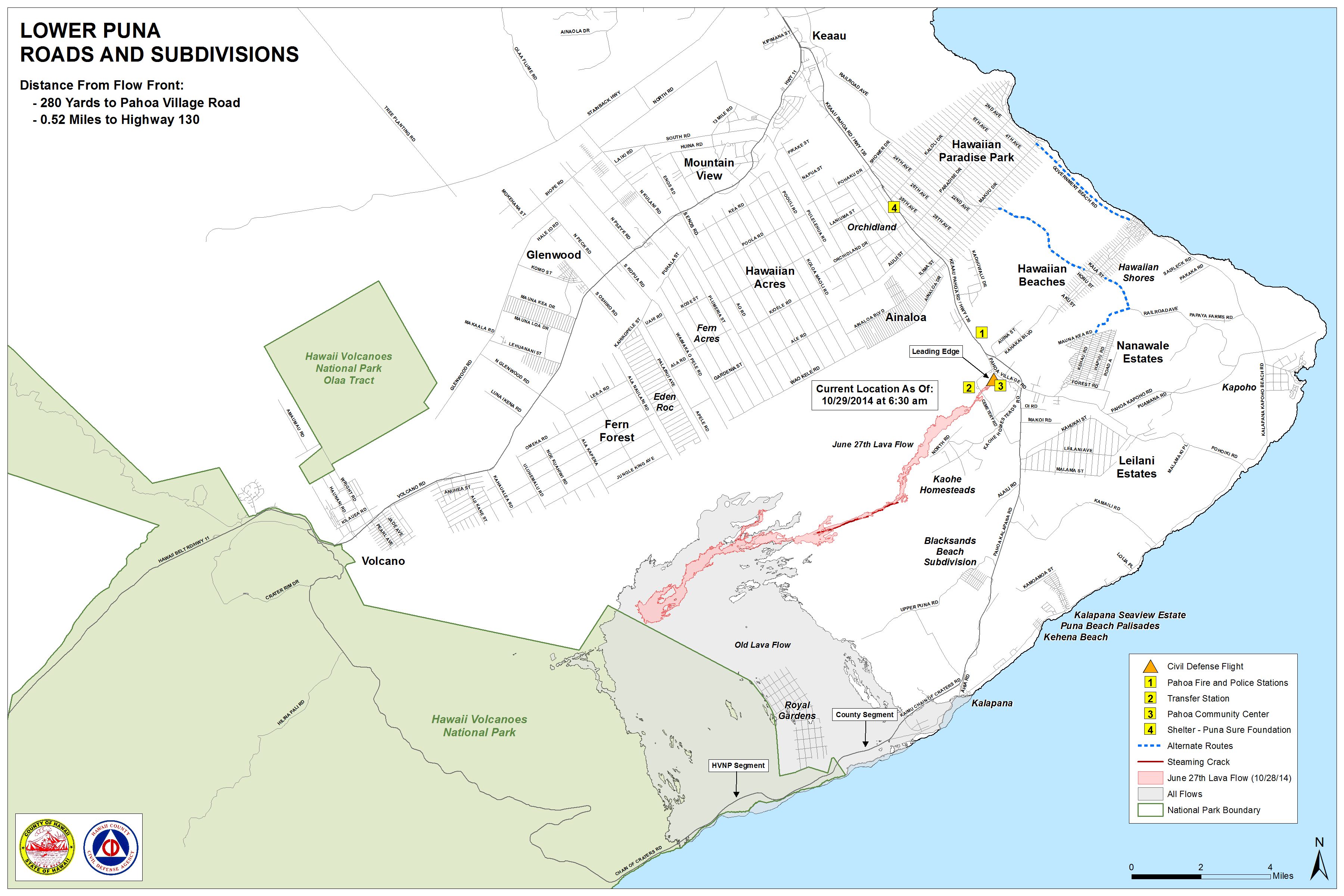

Weeks of grim waiting ended yesterday (Oct. 28) for two homeowners in Hawaii's Pahoa village, as they became the first to lose their yards and fences to Kilauea volcano's relentless river of lava.

The June 27 lava flow now threatens 40 to 50 homes and structures, as well as a major road, according to the Hawaii County Civil Defense Agency. The lava was less than 100 yards (90 meters) from the closest home and 260 yards (240 m) from Pahoa Village road on Wednesday morning (Oct. 29).

Late Tuesday afternoon, the incandescent lava consumed an empty farm shed and incinerated a pile of old tires, sending black smoke billowing into the sky. On Sunday, it had already oozed through a century-old Buddhist cemetery, burying the grave markers. [Photos: Lava Threatens Homes in Hawaii]

Residents in the current flow path were advised of the possible need for evacuation Sunday night. Property owners are allowed to watch the lava pass through their land, officials said.

The lava flow was moving about 11 yards (10 m) per hour late Tuesday, but slowed overnight, reaching a speed of about 5.5 yards (5 m) per hour by 6:30 a.m. Hawaii time, the U.S. Geological Survey said Wednesday. The USGS expects the lava to eventually cross Pahoa Village Road, the statement said.

The smooth pahoehoe lava has streamed a total of about 13 miles (21 kilometers) since June 27, when the new flow broke out from Pu'u O'o crater in Kilauea's East Rift Zone.

Many Pahoa residents have already evacuated from the village, after geologists and county officials alerted them of the possible danger at a series of community meetings in August and September.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Kilauea volcano's incredible 31-year eruption has destroyed more than 200 structures since 1983, including the Hawaii Volcanoes National Park visitor center at Wahaula and homes in town of Kalapana, along with the nearby Royal Gardens subdivision. Lava flows have also blocked Chain of Craters Road in the national park since 1986. But now, because the June 27 lava flow threatens to cut off Pahoa's access to the rest of Hawaii via Highway 130, emergency construction will reopen Chain of Craters Road for the first time in decades.

Despite the losses, there haven't been large-scale efforts to stop Hawaii's lava flows since the military tried bombing Mauna Loa volcano's lava flows in 1935 and 1942. Several reasons dissuade locals and scientists from trying to stem the flow, said Ken Rubin, a geology professor at the University of Hawaii in Honolulu. For instance, lava diversion could have unintended consequences, such as pushing the lava from one area only to direct it toward another community. And cooling the lava with seawater, as was done in Haimey, Iceland, wouldn't work in Pahoa, which is miles from the ocean. Finally, letting the natural process play out is a sign of respect for Pele, the volcano goddess, according to Hawaiians, Rubin said.

But some Pahoa village residents aren't afraid of Pele's anger. Homeowner Alfred Lee built a 12-foot-tall (3.6 m) dirt berm (raised strip of land) to deflect the oncoming lava, he told West Hawaii Today. Berms and buildings can have surprising effects on the lava's path. On Sunday, an old berm from a sugar cane growing operation unexpectedly diverted the lava into an open field, Rubin said.

"As it gets closer to human-made structures and changes on the landscape, it may become less predictable," he said.

Geologists with the Hawaii Volcano Observatory are monitoring the lava flow 24 hours a day.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus