Satellite Searches Could Spot Bigfoot, Loch Ness Monster

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

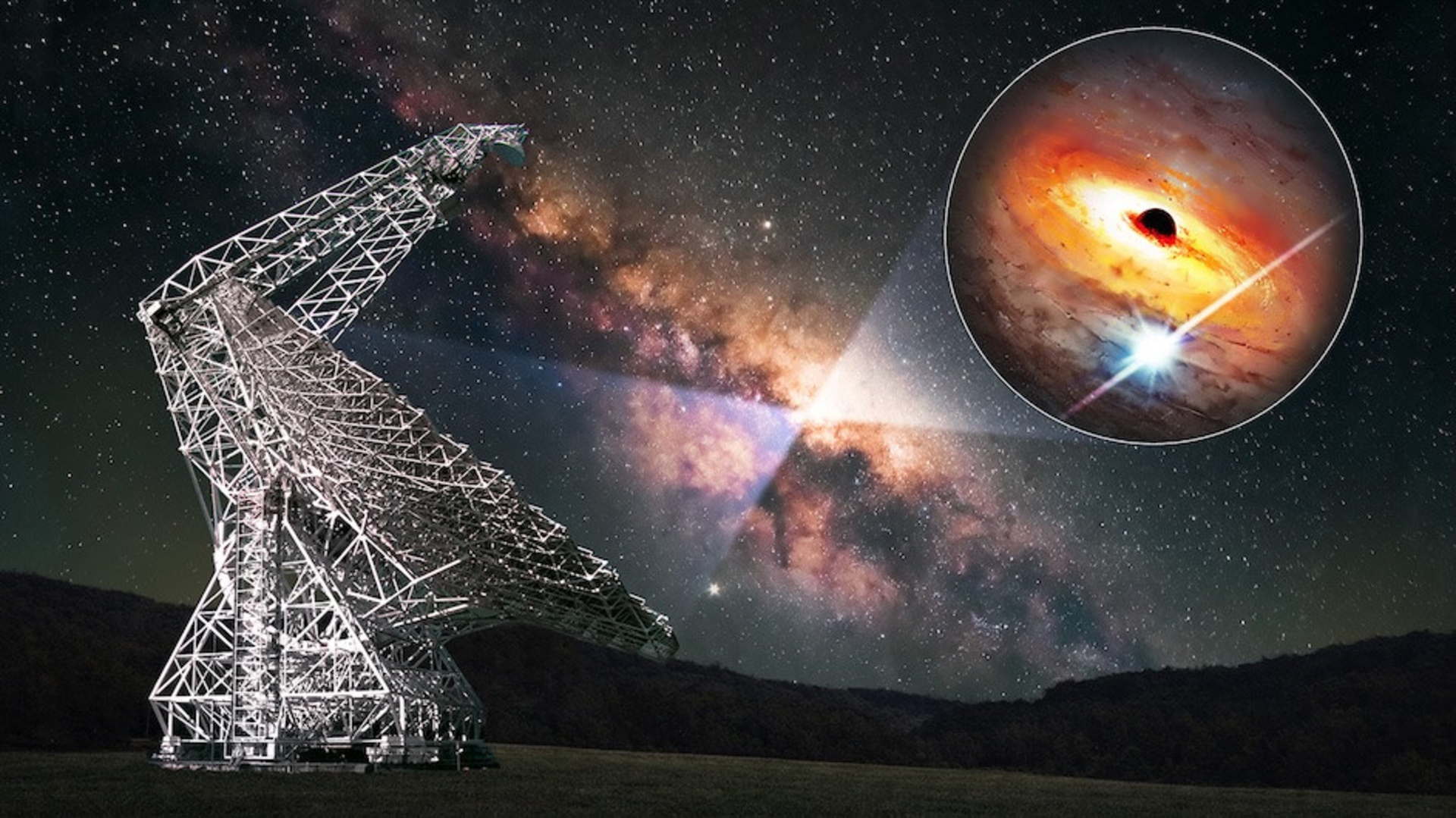

Adventurer Steve Fossett went missing Sept. 3 about 70 miles southeast of Reno, Nevada, in a small plane. He left no flight plan, and searchers have combed tens of thousands of square miles of Nevada and California. After weeks of fruitless searches, and with the survival window closing, Web users were enlisted to help in Fossett's rescue, from the comfort of their own homes. Using a program called Mechanical Turk, high-resolution satellite imagery of the search area was collected and analyzed. Participants were shown a single satellite image and asked to note any objects or wreckage that could be a plane or its debris. The search did solve a few mysteries: several previously unknown small plane wrecks—some dating back to the 1950s—were found. Though Fossett and his plane remain missing, the satellite technology used to search for him could theoretically be applied to other types of searches. It may finally verify the existence of large, mysterious creatures reputed to inhabit the globe. Unknown animals such as Bigfoot and the Loch Ness monster, for example, might be easily located and captured—if indeed they exist. While satellites would be of limited use in heavily wooded areas, Bigfoot creatures have been reported in many places with relatively little forest, including Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Texas and Arizona. A single 12-foot Bigfoot may or may not be hard to spot, but a family of them would be easier to find. Furthermore, there cannot be only one Bigfoot; there must be a breeding population of them, by some estimates 6,000 to 10,000 in North America alone. Surely a coordinated, close search of satellite images would reveal dozens, if not hundreds or thousands, of Bigfoot in remote areas at any given time. The search could include bodies of water as well. Many lake monsters and sea serpents are reported to be 50 feet or longer, and surface regularly where they are seen. If armchair investigators are up to the task, they could monitor monster-inhabited lakes such as Scotland's Loch Ness, Canada's Lake Okanagan and America's Lake Champlain using Google Earth technology. Monster buffs don't need to dip their toes into cold lakes or brave the wilderness to search for their quarry; they can scan a dozen square miles over cup of hot coffee at their leisure. Of course, if such searches are done and still reveal no solid proof of the monsters' existence, few minds will be changed. Diehard believers can always claim that all the monstrous beasts somehow hid undetected or are masters at camouflage. Or the searchers didn't look long enough or in the right places. It only takes one live or dead Bigfoot or lake monster to forever prove that they exist, but no amount of failed searches will ever prove they don't. Benjamin Radford is LiveScience's Bad Science columnist. He is co-author of "Lake Monster Mysteries: Investigating the World's Most Elusive Creatures" (2006). This and other books are noted on his website.

- Top 10 Unexplained Phenomena

- Observing Earth: Amazing Views From Above

- Image Gallery: Breaking the Sound Barrier

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus