Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

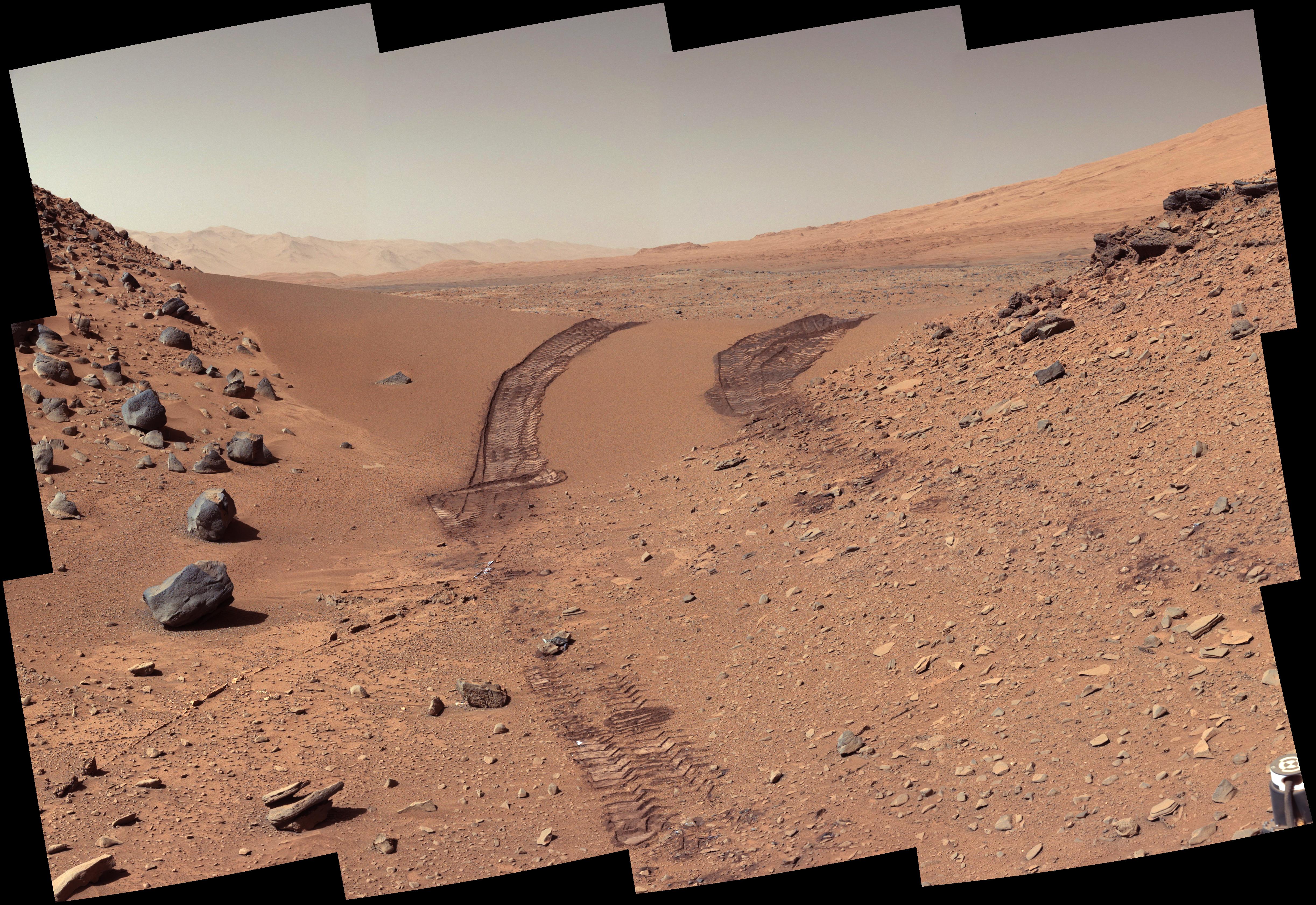

NASA's Mars rover Curiosity has put it in reverse, completing its first-ever long backward drive.

The 1-ton Curiosity rover covered 329 feet (100 meters) in reverse on Tuesday (Feb. 18). The maneuver — carried out over relatively smooth and benign ground — was designed to test out a strategy for reducing wear on the robot's six metal wheels, which have accumulated dings and holes at an increasing rate over the last few months, NASA officials said.

"We wanted to have backwards driving in our validated toolkit because there will be parts of our route that will be more challenging," Curiosity project manager Jim Erickson, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, Calif., said in a statement. [Curiosity Passes 5K Mark, Seeks Gentler Terrain (Video)]

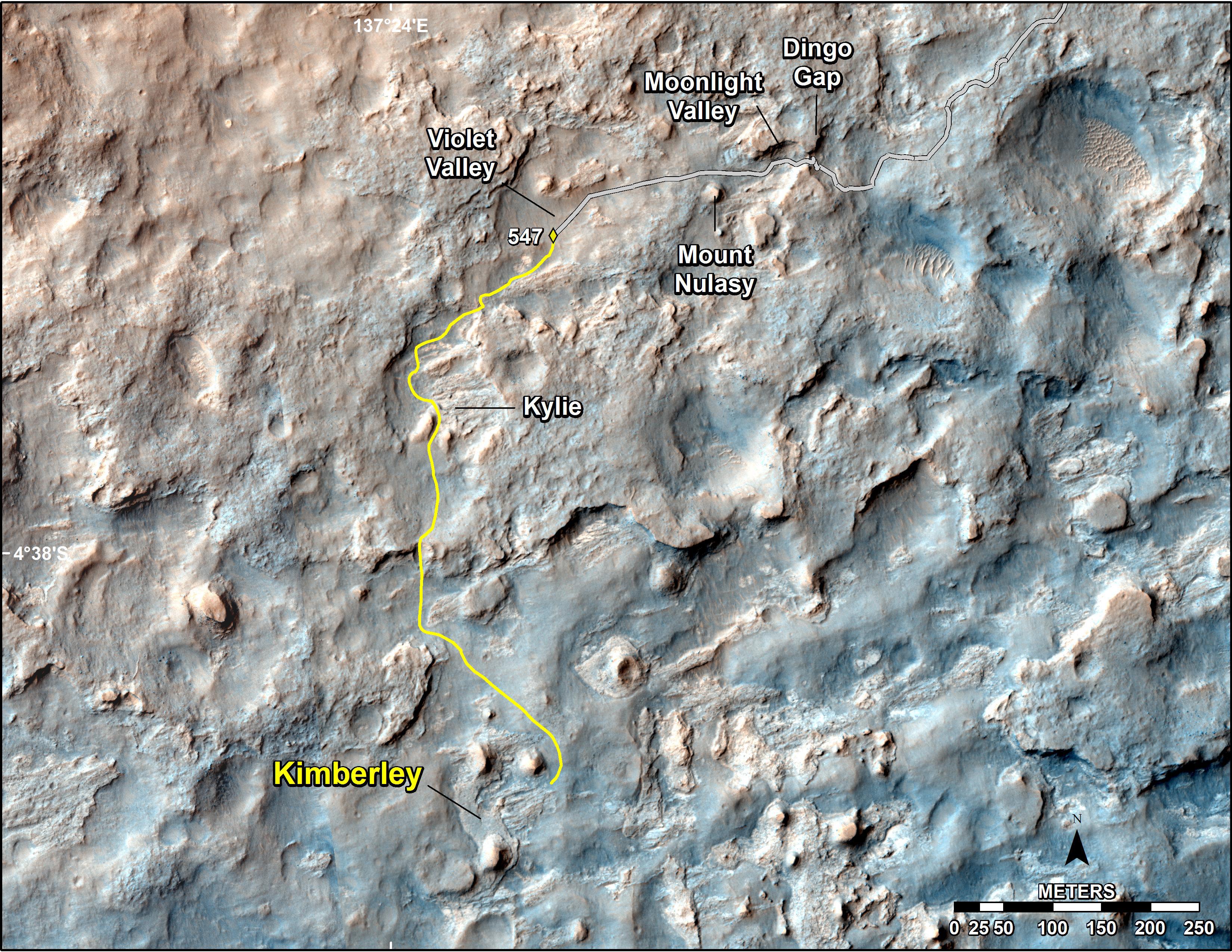

Curiosity is currently embarked on a long trek to the base of Mount Sharp, which rises 3.4 miles (5.5 kilometers) into the Martian sky. The rover recently crossed a sand dune to enter a region called Moonlight Valley, which photos taken from orbit suggested would give Curiosity's wheels a bit of a break.

That landscape assessment appears to be on the money, team members said.

"After we got over the dune, we began driving in terrain that looks like what we expected based on the orbital data," Erickson said. "There are fewer sharp rocks, many of them are loose, and in most places there's a little bit of sand cushioning the vehicle."

Curiosity is expected to arrive at the base of Mount Sharp around June or so. Once there, it will climb up through the mountain's lower reaches, which contain a history of Mars' changing environmental conditions over the eons.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But the rover will stop to do some science work along the way to Mount Sharp. The mission team plans to study — and possibly drill into — rocks at a site they've dubbed Kimberley, which lies about 0.67 miles (1.1 km) ahead on the route.

Curiosity's handlers will further refine the rover's path while it's conducting science work at Kimberley, using orbital imagery to pick the best way forward.

"We have changed our focus to look at the big picture for getting to the slopes of Mount Sharp, assessing different potential routes and different entry points to the destination area," Erickson said. "No route will be perfect; we need to figure out the best of the imperfect ones."

Curiosity landed in August 2012 to determine if the Red Planet has ever been capable of supporting microbial life. Mission scientists have already answered this question in the affirmative, announcing last year that an area near the rover's landing site called Yellowknife Bay was indeed habitable billions of years ago.

Curiosity has now put a total of 3.24 miles (5.21 km) on its odometer since touching down. Its older, smaller cousin Opportunity, by comparison, has driven 24.07 miles (38.74 km) during its 10 years on Mars.

Opportunity holds the American distance record for off-planet driving. The overall mark was set by the Soviet Union's Lunokhod 2 rover, which travelled 26 miles (42 km) on the moon in 1973.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus