Explosive Beer Trick Explained by Physics

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Tapping on the top of a newly opened beer bottle can create a foamy eruption of booze — and get you disinvited from future house parties. Now, physicists have explained this beer bottle phenomenon, and it all comes down to bubbles.

Here's how it works:

A sudden, vertical force against the top of the beer bottle creates a compression wave through the glass, much like the sort of wave you get when you knock one end of a stretched-out Slinky toy. When the compression wave hits the bottom of the bottle, the wave transmits its force back up through the liquid as an expansion wave.

While compression waves compress the beer as they travel through, causing pressure, temperature and density to increase, expansion waves do the opposite, decreasing pressure, temperature and density in the liquid. [Raise Your Glass: 10 Intoxicating Beer Facts]

Now, once the expansion wave hits the surface of the beer, located up by the top of the bottle, it bounces back as a compression wave again. The result is a "train" of expansion and compression waves, all bouncing back and forth between the bottom and top of the bottle, fluid mechanics researcher Javier Rodriguez-Rodriguez of Carlos III University of Madrid in Spain reported on Sunday at the annual meeting of the American Physical Society's fluid dynamics division in Pittsburgh.

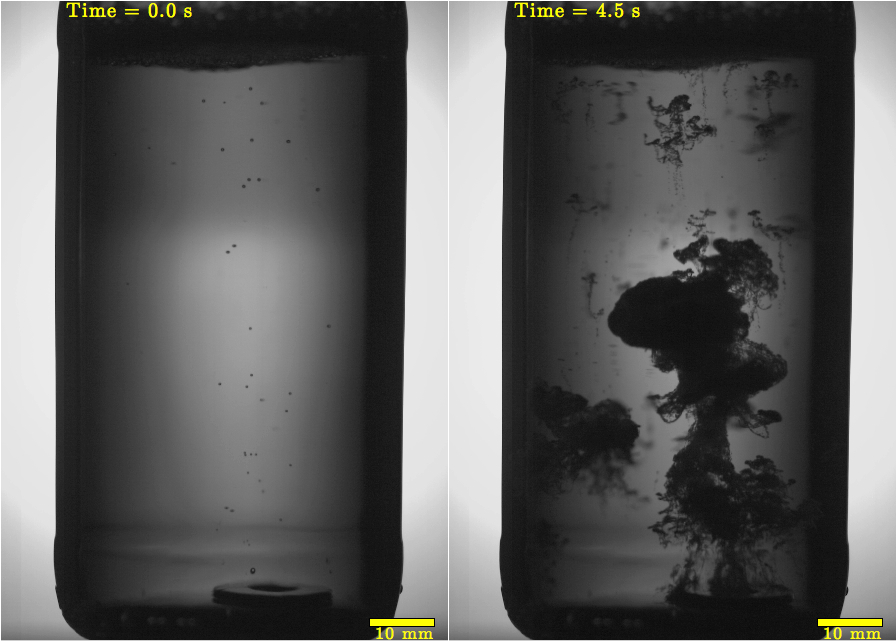

This train of waves causes a big mess. In response to the compression and expansion forces pushing and pulling it every which way, the beer undergoes cavitation, or forms bubbles. Cavitation occurs in response to rapid pressure changes in a liquid, and is important in the engineering of ship propellers. Since these propellers cause cavitation as they spin, the formation and collapse of the bubbles puts chronic stress on the metal.

Cavitation also explains another party trick, in which the bottom of a bottle can be made to explode by hitting the top.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In the case of beer, cavitation creates large bubbles, which rapidly collapse. The collapse of these "mother" bubbles creates multiple, smaller "daughter" bubbles.

These daughter bubbles are the reason the frat-boy prank of tapping on a bottle ends in disaster. The small, carbonated bubbles expand rapidly and gain buoyancy, acting as a life raft for the surrounding liquid. The result is foam, and lots of it.

"Buoyancy leads to the formation of plumes full of bubbles, whose shape resembles very much the mushrooms seen after powerful explosions," Rodriguez-Rodriguez said in a statement. "And here is what really makes the formation of foam so explosive: The larger the bubbles get, the faster they rise, and the other way around."

Explaining this phenomenon may make you the life of your next party, but Rodriguez-Rodriguez and his colleagues studied beer in order to understand bigger-picture gaseous eruptions. One example is the Lake Nyos disaster in Cameroon. Volcanic activity under this lake dissolves carbon dioxide in the water. In 1986, the lake rapidly degassed a large amount of carbon dioxide all at once, suffocating 1,700 people and thousands more livestock. This rapid degassing event, possibly caused by a landslide, could share similar physics with an erupting beer bottle.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus